Erdogan looks set to cement his hold on Turkey – in an election where he’s made all the rules

Ahead of the final presidential vote on Sunday, Erodgan has forced his opponent to change tack to try and close the gap from the first round, writes Borzou Daragahi. It has given him greater control over the narrative of the election

Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan will likely get the election he wanted: an exciting contest that riles up his supporters but leaves his domestic opponents falling short – while being just transparent and free enough to win the grudging nod of western leaders who had hoped he would leave office.

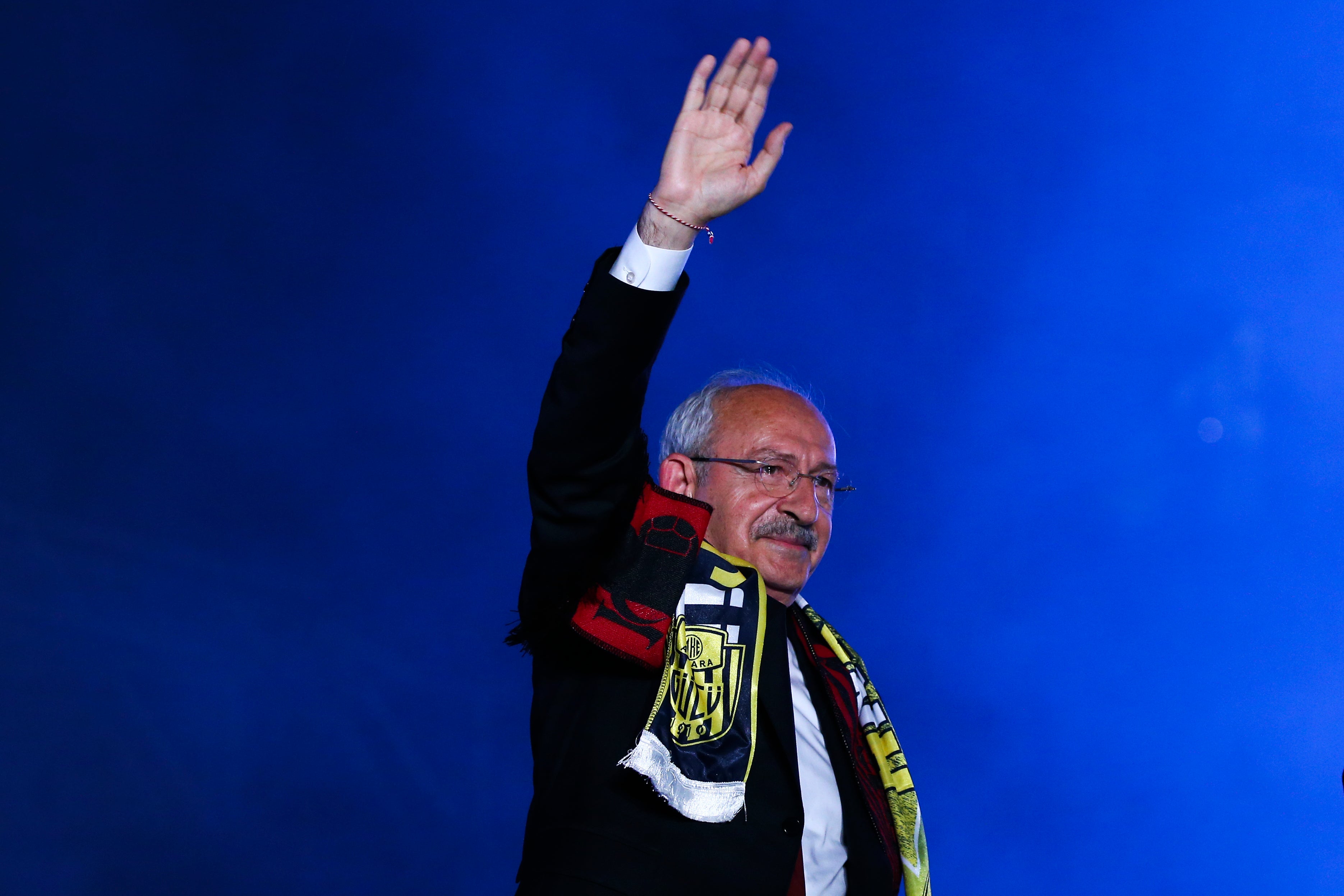

As Erdogan, 69, heads into the decisive second round of the presidential elections this Sunday against Kemal Kilicdaroglu – who is heading up a six-party opposition coalition – all signs point to him cementing his hold over this nation of 85 million for another five years.

The president has faced anger for months over the state of the country’s economy – on a years-long doward spiral – and his government’s slow response to devasting earthquakes that killed 50,000 people in February. But he managed to use his considerable power over state institutions and information channels to shape the election battlefield and came out with 49.5 per cent of the vote in the first round – falling just a half-percentage point or 155,000 votes short of scoring an outright victory – compared with Kılıcdaroglu’s 44.9 per cent.

In the two weeks between the rounds, Erdogan has moved the campaign more into the realm of national identity and security, far friendlier terrain for the president – who likes to project a strongman image – than inflation or the price of the onions, a particular line for Kilicdaroglu. It has also forced his opponent to switch tactics and take a harder line on the issue of migration, with Kılıcdaroglu aligning with an ultranationalist fringe figure to try and win votes.

“I’ve been very frustrated with people who think this could have been a competitive election,” Howard Eissenstat, a professor of history specialising in Turkey at Saint Lawrence University in the US, said in an interview during a visit to Istanbul this week. “Erdogan wants elections but he doesn’t want to compete against people who actually can win.”

Referring to the vast Ankara presidential complex Turkey erected in 2014, the scholar added, “Erdogan didn’t build a 1,000-room place so that he can be forced out in an election.”

Erdogan and his allies can exert control over state broadcast media and almost all major print outlets, putting the opposition at a severe disadvantage from the start of the campaign. In recent days, he picked up the endorsement of far-right nationalist third-party candidate Sinan Ogan, who received five per cent of the first-round vote. On Wednesday Kilicdaroglu’s struggling campaign picked up the endorsement of the ultranationalist Umit Ozdag, the Victory Party leader and a former partner of Mr Ogan.

Opposition supporters hoped Ozdag could blunt the impact of Ogan’s endorsement of Erdogan. However, the backing may ultimately fail to raise flagging morale among opposition supporters. Kilicdaroglu only winning 45 per cent of the first-round vote was disappointing, as it was less than projected in polls and about the same total as opposition parties won in 2018 elections.

The bookish 74-year-old Kilicdaroglu, leader of the People’s Republican Party (CHP), ran a positive if somewhat tepid campaign ahead of the first round. But has since abruptly shifted course, focusing almost exclusively on the issue of immigration and refugees.

Many opposition supporters have been grumbling this week that they may stay home on Sunday, and the scramble to secure the backing of figures considered part of the fringe right may also turn off Kurdish and left-leaning voters. Meanwhile, pro-Erdogan Turks abroad are reportedly voting in record numbers, and pro-Erdogan rallies have continued to draw thousands of people.

Still, the final two weeks of the campaign may return to haunt Turkey. Instead of discussing the crucial needs of those suffering from massive inflation and wages that have not nearly kept up with the cost of living, Turkish politicians have talked about how aggressively to expel migrants and refugees.

Both Ogan and Ozdag, the ultranationalist leaders being courted by both the opposition and the government, have made deporting the four million or so Syrian and other refugees sheltering in the country and suppressing the cultural rights of Turkey’s significant Kurdish minority the centrepieces of their platforms. Both issues have dominated the election campaign’s final days, overshadowing most other issues.

Blaming a country’s ills on vulnerable minorities has historically not boded well for any nation’s democratic growth. Kilicdaroglu had originally promised to move Turkey away from such toxicity. But his campaign has erected giant billboards with the candidate’s face and the words “Syrians will go”.

Erdogan has continued to falsely accuse his opponents of being controlled by the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The separatist group is considered a terrorist organisation by Ankara, Washington and the EU. Kilicdaroglu “has been defeated in 15 elections and is preparing for a new defeat,” Erdogan said in a speech.

The two campaigns have repeatedly clashed – including on Wednesday – over Mr Erdogan’s airing of a video at campaign events that falsely depicted Mr Kilicdaroglu at a PKK event. Mr Kilcdaroglu slammed the video as “slander”. Mr Erodgan’s backers downplayed the video as an illustrative “montage”.

“Is anything of substance being discussed? No,” says the analyst Eissenstat, a state of affairs that will suit Erdogan. “The issue that should have been discussed is the economy”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments