The tortured life of Mrs Helmut Kohl

A new book reveals that the former German leader's wife was raped as a child and hated life in the political spotlight

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

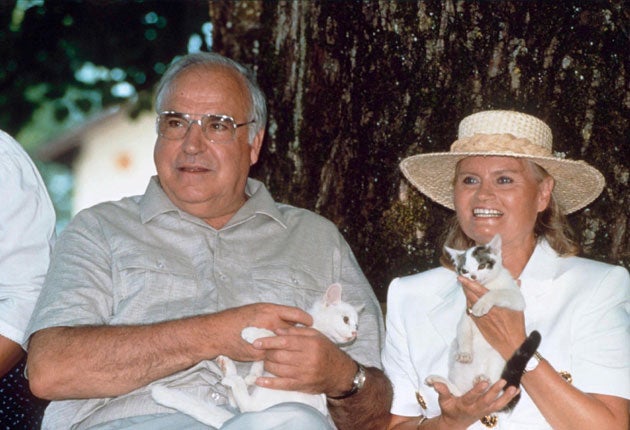

Your support makes all the difference.Hannelore Kohl, the wife of Helmut Kohl, Germany's "unification chancellor", was raped by Russian soldiers when she was 12 and spent her married life in the shadow of her fanatically ambitious husband, a new biography has revealed.

Published this week, The woman at his side – the life and suffering of Hannelore Kohl was written by Heribert Schwan, a journalist who gained unprecedented access to the former chancellor's wife and eventually became her confidant in the months before her death in 2001.

"I understood her openness to be her granting me permission to one day publish what she told me over the months and weeks before her death," Schwan writes. Mrs Kohl committed suicide after contracting a crippling allergy to light which caused her to lose her hair and made even watching television unbearable.

Schwan's biography starts with a graphic and hitherto unpublished account of the traumatic experience which would affect Mrs Kohl for the rest of her life. It describes how the young Hannelore and her mother were set upon by a group of Red Army soldiers in May 1945 and gang raped.

Mrs Kohl recalls how she was "dumped like a sack of cement" out of a first floor window by the Russians, suffering damage to her back from which she would never recover. The psychological scars were worse; Schwan writes that the "smell of male sweat, garlic and alcohol, and even the sound of spoken Russian" haunted her permanently.

Her marriage to Helmut Kohl, at the time a provincial conservative politician in the Rhineland palatinate, began with high hopes. But Hannelore did not expect her husband to enter national politics. When he became Chancellor in 1982, it came as shock. Loathing the glare of publicity, she refused to discuss politics and forbade her two sons to do so.

Schwan cites dozens of occasions on which politics brought Mrs Kohl to the brink of despair. Watching her husband surrounded by party acolytes, she tells one of her women friends: "You can't imagine how much I hate all this." Worst were the Kohls' obligatory holidays at the Austrian resort of Wolfgangsee, where the family was watched permanently by the media and Helmut either entertained a seemingly never-ending stream of visitors or was on the phone

Helmut, Schwan writes, was obsessed by politics, which took absolute priority over his family and his wife. When the "unification chancellor" decided to run again for office in the 1998 general election, Mrs Kohl only learned of his decision by watching the evening news.

Although highly intelligent and fluent in several languages, Mrs Kohl's public reticence, her rigidly coiffured blonde hair and conservative style of dress earned her derisory nicknames such as "Barbie doll" or "the dumb blonde". She suffered because of her public image, but her predicament was worsened by rumours that her husband was having an affair with his office manager.

Schwan reveals that on numerous occasions Mrs Kohl's women friends advised her to divorce him. However, she always rejected the option, claiming that she would be failing in her duty and "giving up".

When Helmut Kohl lost the 1998 election and resigned, Mrs Kohl had hoped to enjoy the life of peace that she had always craved. But within months her husband was at the centre of a major conservative corruption scandal involving illicit party donations. Mrs Kohl was derided as a "donations whore".

By this time she had been suffering for more than five years from a debilitating allergy to light, triggered in 1993 when she took the wrong antibiotics. From 1998, her condition was so severe that she stayed inside her shuttered bungalow by day, going out only at night. In 2001, Hannelore Kohl committed suicide with an overdose of sleeping pills.

The account of her suffering comes only months after publication of an autobiography by her 49-year-old son, Walter. His best-seller also depicts Helmut as cold-hearted and obsessed with politics. Walter severed relations with his father, now 80, eight years ago. Helmut married Maike Richter, 35 years his junior, in 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments