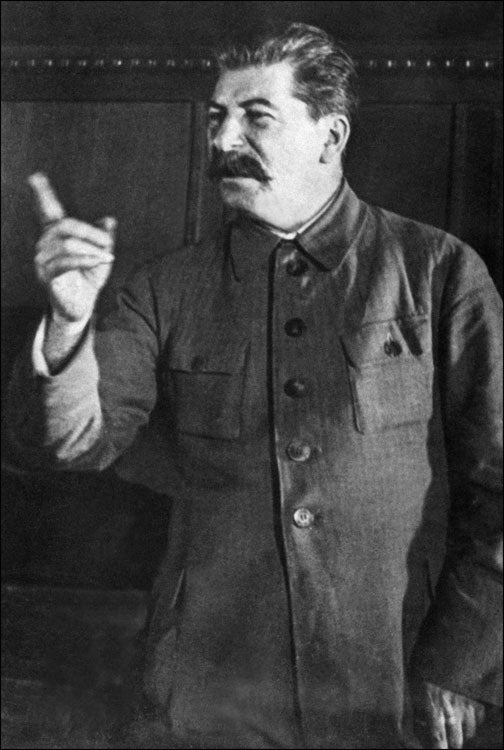

The Big Question: Why is Stalin still popular in Russia, despite the brutality of his regime?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

A competition has been launched to find the "Name of Russia" – one Russian from history who should go down as a national symbol and the nation's biggest hero. Joseph Stalin, despite being one of the most vicious tyrants of the 20th century (and an ethnic Georgian), makes it on to the initial long list of 500 names, and is expected to garner a fair few votes.

Since Winston Churchill won the BBC's Great Britons series, other countries have thought that the concept is a rather good idea. But while the German broadcaster ZDF has said that Adolf Hitler and all other Nazi leaders will be barred from running in the "Our Best" series due to start soon, the Russian version includes Stalin and several other Bolsheviks involved in the Great Terror in its long list.

What was Stalin's rule like?

In a word, brutal. Stalin's most murderous episode came in the purges of the late 1930s, when his paranoid regime executed thousands of Russians – or "enemies of the people" as they were described – who were suspected of disloyalty. Millions of others who avoided execution were sent to remote slave labour camps, known as gulags, where starvation and exhaustion were never far away.

The purges not only showed Stalin's willingness to execute his own people, but also robbed the country of many bright and promising minds. Some blame the purges of the Red Army for its lack of leadership when Nazi forces invaded in 1941.

What is Putin's opinion of him?

Most people agree that Stalin's name, and the Stalin period, has undergone a renaissance during Vladimir Putin's eight years in charge. Putin has never come out and heaped praise on the Soviet leader, but has made several remarks suggesting that Stalinism wasn't all that bad. In a discussion with history teachers, he said that the Great Terror of 1937 was a "scary page" in Russian history, but suggested that the American bombings of Hiroshima and Vietnam were far worse. "We should never allow others to make us feel guilty," he said. Putin has also been instrumental in a rehabilitation of the Soviet past in general. "Yelstin wanted to break all links with the Soviet period, whereas Putin moved to re-establish continuity with the Soviet past," says Boris Dubin, an expert at the Levada Centre think tank in Moscow.

And what about Dmitry Medvedev?

Medvedev is of a different generation to Putin. While Putin was running around East Germany as a KGB spy, Medvedev was playing air guitar to Deep Purple records and dreaming of owning a pair of jeans. During his election campaign, he told youths at a rock concert that everything had been "grey" during the Soviet period. In his speeches, he has also focused less on making Russia strong and powerful, and more on improving economic and civil freedoms for its citizens. How serious he is, and how much he'll be able to change things, remains to be seen, but it's a fair bet that his views towards Stalin are less charitable than Putin's.

Nevertheless, while it's unlikely that Medvedev would publically praise Stalin, one of his first speeches as President was to take over command of the Presidential Regiment from Putin and congratulate it on its 72nd anniversary. The regiment was formed in 1936, just before the Great Terror, to protect Stalin. The improbability of Angela Merkel offering similar congratulations to a regiment formed during the Nazi period shows just how differently Russia and Germany look at the "dark" parts of their histories.

How do Russians see the Stalin period?

A survey from late 2006 found that 47 per cent of Russians viewed Stalin as a positive figure, and only 29 per cent as a negative one. "Lenin is slowly becoming a historical figure with little contemporary relevance," says Mr Dubin. "But as we focus more and more on the Great Patriotic War [Second World War] as the main event in our 20th-century history, the figure of Stalin becomes more and more significant to ordinary Russians."

Under Putin, Victory Day has become the biggest Russian holiday, and for most Russians, the name of Stalin is synonymous with the Second World War effort. Western scholarship that suggests Stalin refused to believe that Hitler would attack the Soviet Union in 1941 and thus cost thousands of lives is rubbished, and there is also no discussion of the forced deportation of millions of Soviet citizens – Chechens, Volga Germans, Kalmyks and others.

What are children taught about Stalin?

A new, government-approved history textbook was launched last year to much controversy. The book covers the 20th century, with a chapter at the end on Vladimir Putin and "sovereign democracy". The textbook portrays the Stalinist repressions as a necessary evil: "The result of Stalin's purges was a new class of managers capable of solving the task of modernisation in conditions of shortages of resources, loyal to the supreme power and immaculate from the point of view of executive discipline." A few historians would argue with that analysis.

Who else is in the Name of Russia list?

Among the 500-strong long list are a range of names, from Tsars and aristocrats to the Soviet goalkeeper Lev Yashin, via composers, poets and artists. It will be whittled down to 12, with the winner announced in December.

Vladimir Lavrov, a history professor at the Institute of Russian History, was given the task of selecting the 500 candidates. He said there were some figures who "couldn't be seen as a symbol of the country, such as Lavrenty Beria". Beria was one of Stalin's cruellest henchmen. Other controversial Bolsheviks on the list include Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the Cheka, eventually renamed the KGB.

Does Stalin have a chance of winning?

It is not known who is leading the vote, but Stalin's popularity among a certain section of the population makes it quite possible that he will make the 50-strong shortlist, and perhaps the final 12.

But he faces stiff competition. Peter the Great, who founded St Petersburg, is likely to win a lot of support. The clever money would be on the poet Alexander Pushkin. Although he died in his 30s, Pushkin is by far the most popular Russian literary figure, with streets, squares and cities bearing his name. Every Russian schoolchild can recite at least a few verses of his poetry, and as the popular Russian saying goes: "Pushkin is our everything."

Is Stalin likely to continue becoming more popular in Russia?

Yes...

* As time goes by, the repression and murder of the epoch is forgotten, while there is a nostalgia for superpower status

* The state controls TV, which continues to make patriotic programmes about Stalin and the war that gloss over the repression

* Russians traditionally respect a strong leader more than they worry about human rights or democracy

No...

* Russians will continue to respect for those who fought the Nazis, but they can separate this from respect for a vicious dictator

* Young Russians may not be democrats, or politically engaged, but nor do they have any time for Communism or Stalinism

* After Putin, state propaganda could turn away from portraying the Soviet past as glorious, and adopt a more nuanced approach

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments