The Big Question: Why can't Italy rid itself of the scourge of football hooliganism?

Why are we asking this now?

Italian fans erupted up and down the country on Sunday after a Lazio fan was accidentally shot dead by a policeman at a motorway service station. The violence was particularly wild at the stadium in Bergamo, where fears for public safety led to the game between Atalanta and AC Milan being called off after seven minutes.

Doesn't football hooliganism break out every weekend?

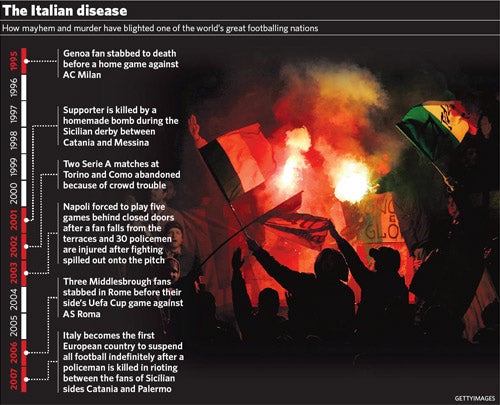

It was certainly a running problem, until matters came to a head nine months ago. A derby match in the Sicilian city of Catania between Catania and Palermo exploded in spectacular violence inside the ground. When play was halted, the "Ultras", as Italy's extreme fans are called, poured on to the streets and continued battling with police in scenes that were carried live on television news and shocked the nation.

At the culmination of the violence, a local policeman called Filippo Raciti was struck by a missile thrown by a fan and later died in hospital. His death provoked an impassioned debate about where Italian football was heading, and the government passed a law mandating change.

So what has changed?

Security is far tighter inside Italian football grounds this season, though still nothing like as rigid as in Britain. Turnstiles and named tickets have been introduced, making it possible for the first time for clubs to monitor and ban turbulent fans. And the cosy relationship between the management of clubs and their "Ultras", whereby club chairmen indulge the rampages, racist chants, obscene banners and flare attacks of the violent fans, has been checked if not abolished. For the first time in many years the Ultras can no longer swagger into the ground with no real checks and do as they please.

Doesn't the latest incident suggest that the problem persists?

That is certainly one interpretation: there are plenty of despondent football-lovers in Italy this week, lamenting the death of the game, the criminalisation of football supporters, the barbarisation of the whole sport. But then over-the-top responses are normal in Italy.

Why was the fan shot dead?

The full story will emerge at the trial of the officer, who is expected to be charged with murder. But according to his own testimony yesterday it was a grotesque and improbable accident; the officer apparently intended to fire shots in the air to force a car that was leaving the service area at speed to stop, but he fired his pistol when he was running and instead of going safely upwards his second shot penetrated the neck of the fan sitting in the back of his car, who was asleep at the time.

So the shooting was nothing to do with crowd violence?

The car leaving the service area at speed allegedly contained Juventus fans, who shortly before had exchanged punches and kicks with two car-loads of fans of the Roman club Lazio. So the incident was connected with crowd violence in the sense that, as fighting has been made more difficult inside the grounds, Ultras increasingly stage their scraps a good distance away. But according to one report yesterday, the officer who fired the fatal shots was not even aware that a brawl was going on at the other side of the motorway.

Why did fans react so violently?

While there are frightening rivalries between the fans of particular Italian clubs – the two sides from the capital, Roma and Lazio, for example – all Italian Ultras regard all Italian policemen as their common enemy. In the Ultras' parlance, there is a war going on between the two sides, and the death of Filippo Raciti and the surge of indignation and revulsion against crowd violence right across Italy that followed his death enabled the police to make important gains in the "war". The silence of the "north curve", the corner of the ground where Ultras congregate, the moderation of the language of the banners they carry, in some cases the disappearance of the banners altogether, made it look as if the crushing of the Ultras was close at hand.

The accidental death at the weekend allowed them to seize the initiative again, to show the world that they are still around, still a menace and capable of acts of spectacular destructiveness. Capable also of impressive feats of collective self-pity and self-dramatisation.

So how does the Ultras' 'logic' work?

After Raciti's death, Italian football was closed down for an entire week. On Sunday initially only the Lazio-Inter game was cancelled – so hundreds of Ultras demonstrated in Milan and elsewhere with banners lamenting "All deaths are not equal". Yet as several observers pointed out, the deaths were not remotely comparable: it was clear from the outset that the killing of Gabriele Sandri was an accident unrelated to football, while Raciti died combatting fan violence. It was also by no means clear that if the authorities had gone ahead and cancelled all games, as several politicians said they should, the result would have been a quiet and sober day of mourning.

In Rome, for example, the match scheduled for the Olympic stadium last night was cancelled – but the area around the stadium was the scene of the worst rioting in the country, with 40 policemen injured and damage to property estimated at at least 100,000 euros.

Is there a positive way of interpreting Sunday's mayhem?

The most optimistic interpretation is that these are the death throes of a form of crowd behaviour that the Italian state has made clear it will no longer indulge. The past months have shown that it is possible to induce fans to behave in a more civilised manner. The challenge the authorities face now is to prove that they are still serious about that, and are prepared to do what it takes to face down the newly resurgent Ultras.

The stakes are high: the government has indicated that it is willing to close down the whole football industry again, as it did in February. The clubs, which earn far less from television rights than their English equivalents (because clubs negotiate their fees individually), and whose accounts are notoriously shaky, cannot afford that.

Will Italian football continue to be racked by crowd violence?

Yes...

* If the fans responsible for the damage in Rome and Bergamo on Sunday are let off the hook

* If clubs allow the Ultras to return to their violent, provocative ways

* If another incident like Sunday's shooting occurs soon, in which case all bets are off

No...

* If politicians stick to the tough line they have pursued since February

* If the minority of violent fans decide the light is not worth the candle

* If the government begins to tackle problems of insecure employment, worthless higher education and social decay which reinforce nihilistic behaviour

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks