Spanish election: How the youth of Spain may hold the key

The vote on 20 December could upset the status quo

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Spain’s youth could be forgiven for thinking they don’t matter. During the recent recession, the unemployment rate for under-25s rose sharply – it is still nearly 50 per cent – and thousands of people emigrated to look for work. It’s hardly surprising that young people are among the keenest to use today’s general election to end the two-horse, left-right political divide which has dominated the country for more than four decades.

“It’s time to move on from what we’ve seen for so long,” said Adriana Hernando Sierra, an 18-year-old and first-time voter. “It’s about giving a chance to new people with different ideas about how to run this country.

“Many of my friends are keen to vote because they see this as an opportunity for real change. We’re all talking about that.”

Ms Hernando Sierra’s vote will be going to the centrist Ciudadanos party which, together with the left-wing, anti-austerity Podemos, are the two new major political players hoping to end the familiar battle between the socialist PSOE and ruling right-wing Partido Popular (PP).

A poll earlier this month confirmed that rejection of the PP is strongest among Spain’s younger generations; 58.2 per cent of 18- to 24-year-olds said that “they would never vote for them”; and among 25- to 34-year-olds, that percentage rose to 64.2 per cent.

The PP has held a parliamentary majority since 2011; the economy is now showing steady growth, with overall unemployment at more than 21 per cent, but the PP has been hit by a number of alleged corruption scandals.

Asked which party they would vote for if elections were held the next day, 14.2 per cent said Ciudadanos – compared with just 1.9 per cent this January; the PP trailed in fourth place, at 9.9 per cent. However, in another indication of why these elections are considered the most unpredictable in Spanish modern democracy, 52.9 per cent of 18- to 34-year-olds said they were still undecided which party to vote for, more than 10 points higher than the national average.

According to the latest polls, the PP is expected to gain the most parliamentary seats following the vote, but lose its majority. But, all four parties – the PP, PSOE, Ciudadanos and Podemos – have received between 18 and 26 per cent support in recent polls.

The fact that both Ciudadanos and Podemos have not been involved at elections on a national level before is also adding to the unpredictability, although the PP and the PSOE are expected to benefit from Spain’s system, which gives a higher proportion of seats to rural areas with fewer voters.

What is clear, though, is that the PP’s appeal to Spain’s younger generations has ebbed notably. At Ciudadanos’s end-of-campaign rally on 18 December in a central Madrid square, during the hour-long wait for leader Albert Rivera to speak, there was certainly a palpable sense of youthful energy in the air.

Noisy rock music blared out, with well-dressed young people predominant among the 3,000-strong crowd. Young parents wearing orange Ciudadanos scarves watched over their children in the square’s two small playgrounds between sips of free hot chocolate.

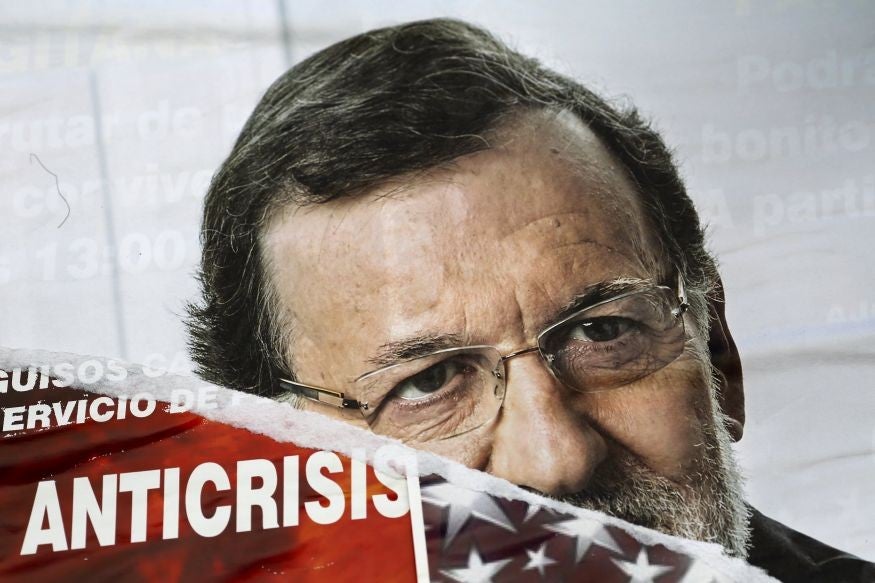

When the party’s campaign video started up on the giant screen, it showed Mr Rivera (at 36 he is 24 years younger than the current Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy) writing a letter to his daughter Adriana about his hopes for Spain’s future.

Mr Rivera is not the only youthful leader in the election; Pablo Iglesias, the leader of Podemos, is a pony-tailed, 37-year-old political science professor, known for preferring jeans to suits.

At the Ciudadanos rally, as he waited for the speakers, Pedro Carrasco, 25, made his case for voting for the party. It is “not just a change of old politics vs new”, he said.

“It’s an ideological change from that left and right divide. After so many young people emigrating to work because there’s none here, trying to create a life for themselves … we need that change.”

Francisco, 22, juggled his mobile phone and three Ciudadanos flags. “The PP and the Socialists had forgotten about the younger generations, and that’s why we’re here,” he said.

However, a clean break with the past may well be tricky, given the bewildering and unprecedented range of potential government coalitions that could be thrown up by a new Spanish parliament with no clear majority for any one party.

The uncertainty of the elections on 18 December has led to the PP urging last-minute waverers to vote for them if, as Mr Rajoy put it, “you don’t want nightmare alliances”. He warned that “Spain is not somewhere to play at Russian roulette”.

Others have also tried to make clear that they are the only viable option; the Socialists described themselves in their final campaign leaflet as “the only alternative to four more years of Rajoy”.

However, Mr Rajoy is perhaps not as confident as he tries to appear, having also left the door open to an alliance with other parties in order to prevent a leftist coalition government from emerging after general election.

Alliances would also not be on the wish list for those who seek a complete overhaul of the government. “It would be a real let-down if there were alliances,” said Jose Ballesteros, a 31-year-old doctor in Almeria, south-east Spain, who plans to vote for “one of the new parties”.

“I get the feeling that they [the alliances] were more interested in political power than in really making a change.”

Cristina Moya, an unemployed cleaner from Andalusia, said: “It would be terrible if after all this talk of change, the new parties let the old parties back in power.” The 27-year-old said that she would “probably vote for Podemos, although I’m severely disillusioned with politics in general”.

But even those members of the younger generation who are still loyal to Spain’s old-style parties believe that the arrival of Podemos and Ciudadanos has been beneficial in shaking things up – although the process needs to continue.

“It’s been harder fought than other political campaigns and that’s meant politicians have become more aware of what people are really talking about, their real concerns,” said Ainara Hernando, a 28-year-old writer from Vitoria in the Basque country and who admitted to being a “life-long PSOE voter”.

“The politicians still need to be more in touch with the real world,” she said. “There are still too many who have no idea what such a high level of youth unemployment really means, or even how much a cup of coffee costs in a local bar. That basic stuff – too often it’s still lacking.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments