‘Not just about Ukraine’: Why Romania is one of Kiev’s strongest supporters in Russia dispute

Some European nations have been criticised for their lack of support for Ukraine, but not Romania, which has its own security fears about any conflict with Russia

The crisis in Ukraine is prompting Romania to take on a more active military and security role in eastern Europe than at any time in its recent history, providing support to both Kiev and its Nato allies.

Bucharest has in recent days publicly welcomed possible deployments of American and French troops to bolster a contingent of nearly 1,000 United States military personnel already in the country at several bases, including a sophisticated Aegis Ashore Missile Defence station in the southern city of Deveselu.

Romania has for several years been providing Ukraine with cybersecurity backing, intensified talks with Kiev on strengthening naval security cooperation in the Black Sea and given Ukraine what one former foreign affairs adviser called “unconditional political support” as it confronts a potential incursion by Russia.

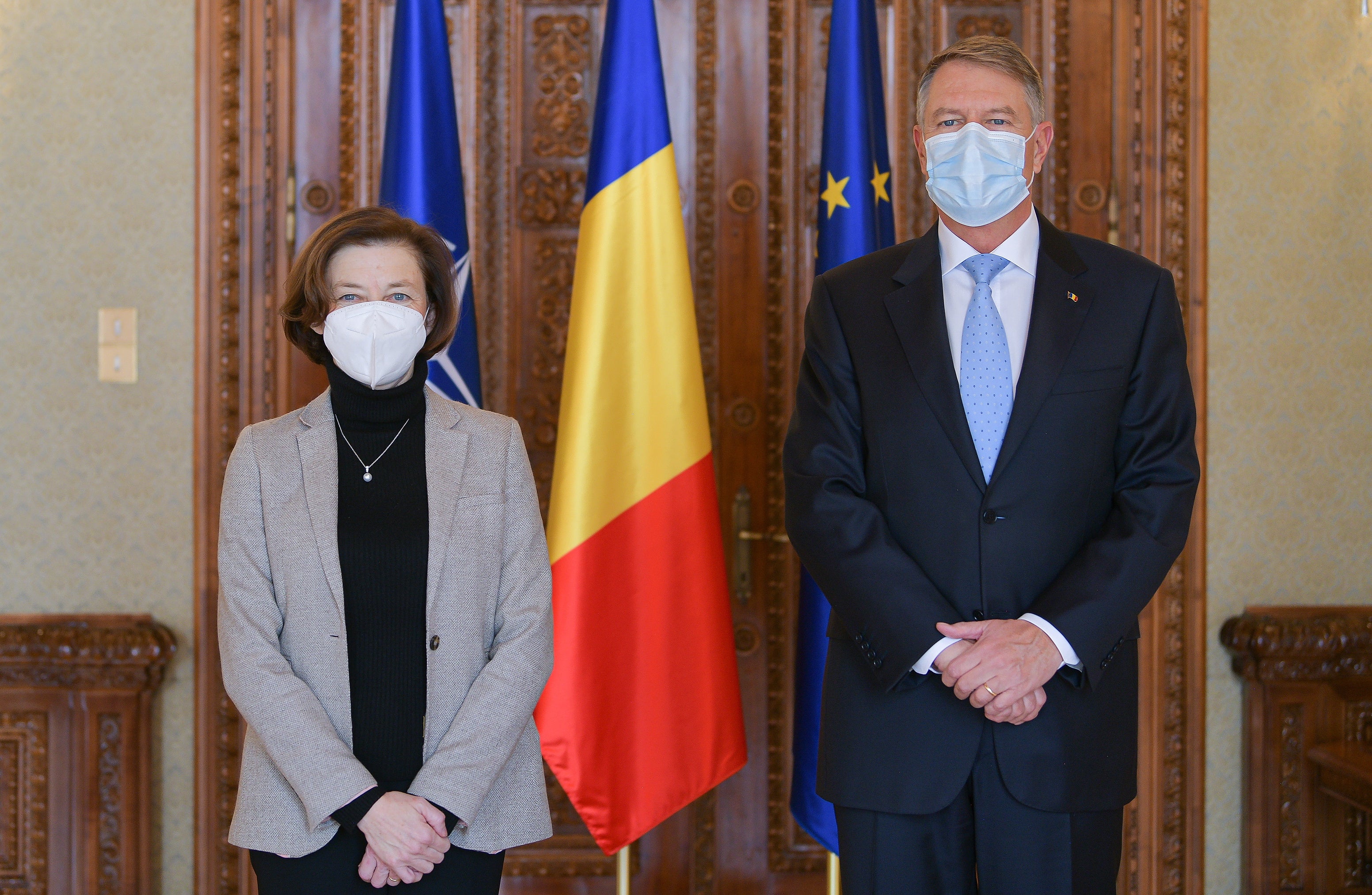

“We must be prepared for any possible scenario,” Romanian President Klaus Iohannis said in a statement on Wednesday. “The crisis is not just about Ukraine, security on the Black Sea, or European security, but about the security of the Euro-Atlantic area.”

French armed forces minister Florence Parly, after meeting with Romanian counterparts on Thursday, said a team of experts was arriving in Romania to sketch out a possible deployment.

“The current security situation is worrying on the eastern flank of Europe,” she said. “Romanians are rightly anxious to strengthen their own security, as tensions in Ukraine continue to escalate.”

Perhaps no other eastern European country has embraced its role as a possible deterrent against a possible Russian invasion of Ukraine as enthusiastically as Romania, which joined Nato in 2004.

“Romania is Nato’s military pillar for southeast Europe,” said Radu Magdin, a former foreign policy adviser to the Romanian government. ““It’s the hub for southeast Europe. You have so many facilities, either Nato or bilateral.”

The withdrawal of Nato forces from Romania and Bulgaria was among Russian president Vladimir Putin’s publicly stated demands for avoiding a clash over Ukraine, prompting a measure of alarm in Bucharest.

Late Wednesday, diplomatic convoys could be seen rushing across the capital in black Mercedes sedans. Among Romanian youth there are worries that war is imminent, and that they could be drawn into fighting any conflict.

Few believe that Russians would attempt to invade Romania itself. Driving Romania’s anxiety is not only the security of Ukraine, with which it shares a 373-mile border, but the complicated potential role of Moldova in any conflict involving Russia and Nato.

Romanians worry that any incursion into Ukraine could trigger instability and spillover in Moldova, a largely Romanian-speaking nation of 2.6 million over which it has clashed with Russia for centuries. The former Soviet Republic is regarded by many as part of historical Romania.

The Kremlin-controlled territory of Transnistria, a Russian-occupied district of Moldova, remains Moscow’s western-most garrison, just 100 miles from the Romanian border, and has been cited as among the ways Russia could launch a front against Ukraine.

While many analysts speculate that the weapons and equipment in Transnistria are dated, there is no guarantee Russia has not supplied its estimated 1,500 troops there with advanced weaponry, or could do so on short notice.

“We’re cautious about the surprises that Russia may cause us in Moldova,” said Mr Magdin. “More of a Nato security presence here, means more security for Romania.”

With a population of 19 million, Romania is one of the largest countries in eastern Europe. Its ethnic diaspora includes significant enclaves in Serbia and Ukraine, both of which are vulnerable to Russian influence and pressure. But it has been consumed by internal matters for years, shying away from eastern Europe and mostly restricted its foreign policy focus to the European Union and Nato.

Perceived Russian assertiveness over Ukraine may be changing that.

Romanian animosity toward Russia runs deep.

It is rooted in repeated Russian invasions over the centuries and what Bucharest regards as the century-old theft by Moscow of precious golden relics belonging to the country’s long deposed royal family. Romanian armed forces enthusiastically collaborated with Nazi Germany against Russia during World War II, including in the siege of Stalingrad.

Following the fall of the Communist regime in 1990, Romania was among the most enthusiastic former Warsaw Pact nations to join in western security and economic blocs, including the EU, which it joined in 2007. Fear of Russian ambitions in part drove the pivot.

“The Romanian intelligentsia knew even in the 1990s that we had a limited window of time before the Russians would eventually recover,” said Mr Magdin. “So we had to get into all of the clubs as fast as we could.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks