Roman Protasevich confession lifts lid on Lukashenko’s use of torture

The interview has led to further calls to isolate the Belarus regime

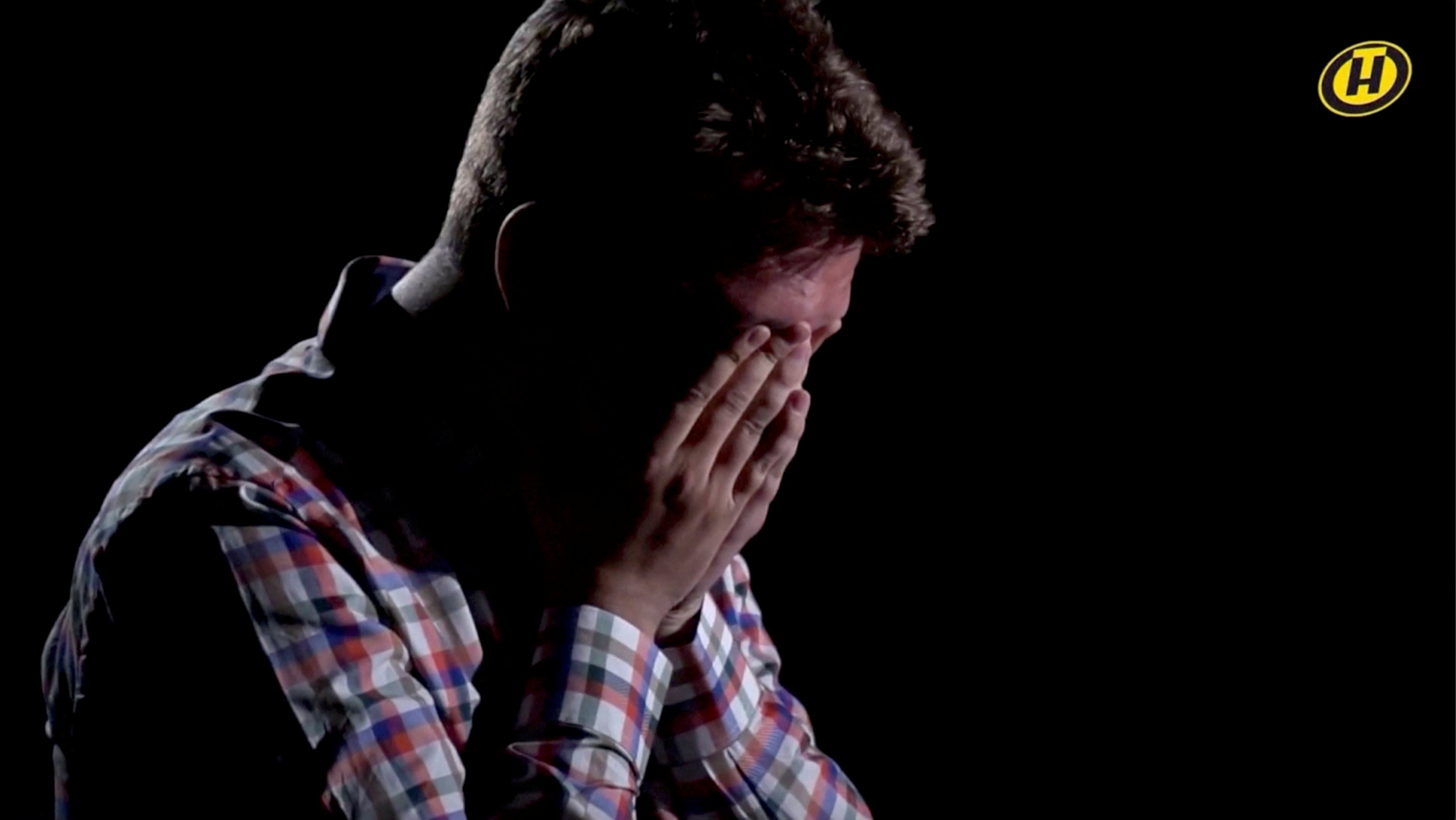

The competition is strong, but perhaps the most excruciating part of Roman Protasevich’s painful “confession” interview, published on state TV on Thursday night, is the end.

It is a moment when the jailed journalist cries and rubs his eyes – only to show deep indents left from handcuffs, freshly cut into his wrists.

That image should have been more than enough for those who hadn’t been paying attention for the hour-and-a-half beforehand: Roman Protasevich is being subjected to torture after being plucked from a Ryanair 737 by the long arms of Belarus’s erratic autocrat, Alexander Lukashenko.

His father, Dmitry Protasevich, not without reason, has said that his son was forced to deliver a script. “It’s not him speaking, and you can see he is fighting with himself when he is delivering what they want him to say,” he told Russian media afterwards. “Perhaps they threatened to kill him or his girlfriend.”

With this in mind, the “confessions” obtained by the so-called interviewer Marat Markov, a former member of Lukashenko’s administration, need to be viewed with every caveat.

In other words, Protasevich was not praising Belarus’ disputed president as a “man with balls of steel”. He does not “unquestionably respect him”. He was not confessing to planning a coup. He did not say that Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, Belarus’s president-in-exile, who almost certainly beat Lukashenko last August in elections, is being funded by Lithuania and shadowy oligarchs. And he was not making a promise “never to take part in politics again”.

For those who have followed Mr Lukashenko’s 27-year rule close up, the odious state -TV show touched on familiar ground.

Victoria Fedorova, who heads the International Committee for the Investigation of Torture in Belarus, said she doesn’t doubt “for a minute” that Protasevich had been “worked over”.

The depth of the cuts on his wrists suggested either that handcuffs had been deliberately dug in, or he had been hanging from them in his cell, she argued.

And that was only what we saw: there are other many “medieval” methods in use by Lukashenko’s regime that leave little to no visible evidence. Her group has documented many of those methods in 1,300 witness statements from victims of Mr Lukashenko’s post-election clampdown.

“We didn’t see under his shirt, and we can’t know the other pressures he is being put under,” Ms Fedorova said. “The threat of being handed over to insurgent fighters in Luhansk, a grey zone with no rule of law, for example, would have been a very weighty argument.”

Earlier this week Mr Lukashenko claimed he was considering a request from officials of the Russian-backed separatist authorities in Donbass to hand over his number-one prisoner. He suggested Mr Protasevich might have to worry about the death sentence.

Even if Mr Protasevich is spared what would amount to an extraordinary extra-legal move, the Belarusian prison system has shown it is more than capable of matching the worst in the world.

At the peak of the clampdown in August-September, as many as 1,406 people were subjected to police violence, according to one investigation. A third of those incidents resulted in serious injury. There were at least three cases of rape while in police detention. One of the victims was a minor.

As many as 450 political prisoners remain at Mr Lukashenko’s pleasure, with the health of the vast majority of them unknown. The spectre of activist Stepan Latypov’s attempted suicide in court on Wednesday would appear to give some clues about detention conditions.

Ms Fedorova says her group has documented torture by electric shock, sleep torture, beatings, and other serious injury. There was also evidence of prisoners being deliberately infected with coronavirus, and even being mocked with poisonous chemicals.

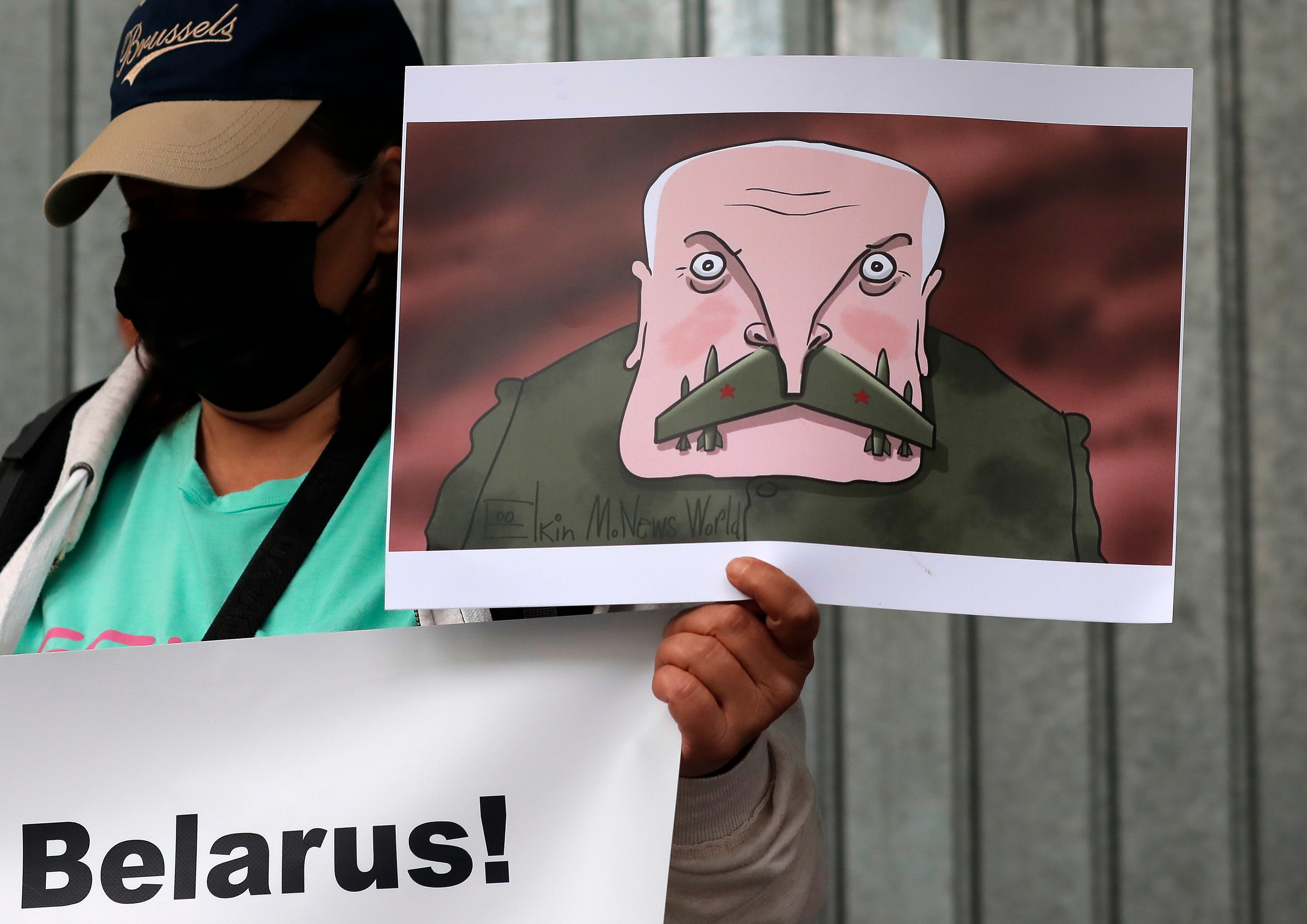

The forced television interview has led to calls to isolate Lukashenko’s regime even further.

Kenneth Roth, the head of Human Rights Watch, said the video “should be Exhibit A in a prosecution for torture and ill-treatment under President Lukashenko”.

And Ms Tikhanovskaya urged major powers to push harder against the Belarus regime in the run-up to next week’s G7 summit in Britain.

“Pressure is more powerful when these countries are acting jointly, and we are calling on [the] UK, the USA, the European Union and Ukraine. They have to act jointly so their voice will be more loud,” she said.

France has said it would like to invite the Belarusian opposition to the G7 summit, if host country Britain agrees.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks