Refugee crisis: Pressure grows along the migrant trail to close Europe's open borders

Hungary has already shown it is not afraid to shut its borders, using razor wire and handing out long prison sentences to those who cross

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.With Slovenia behind them and Austria just ahead, the asylum seekers shoved at the metal barriers blocking their path and chanted a plea into the smoky night air: “We want to go!”

Nearly 1,000 people had been waiting all day for the border crossing to open, penned into a no-man’s land by twitchy troops armed with pistols and assault rifles who met requests for food or water with stern commands and glares icy enough to match the fast-falling temperature.

“We’ve already spent two nights outside,” said Galia Ali, pointing to her severely disabled 8-year-old son, who lay shivering on a blanket near a dwindling fire. “If we’re still here in the morning, he’ll be dead.”

Hours later, the barriers were lifted, and the migrants surged into Austria. But up and down the route being traveled by a historic number of migrants this year as they seek new lives in Europe, pressure is building to close the continent’s cherished open borders for good.

Hungary already has proved that it can largely insulate itself from the refugee crisis by deploying razor wire and threatening lengthy prison sentences for anyone who dares cross it. The country’s moves have shifted the burden of the refugee crisis to its neighbors — and are now tempting leaders in those nations to build their own fences.

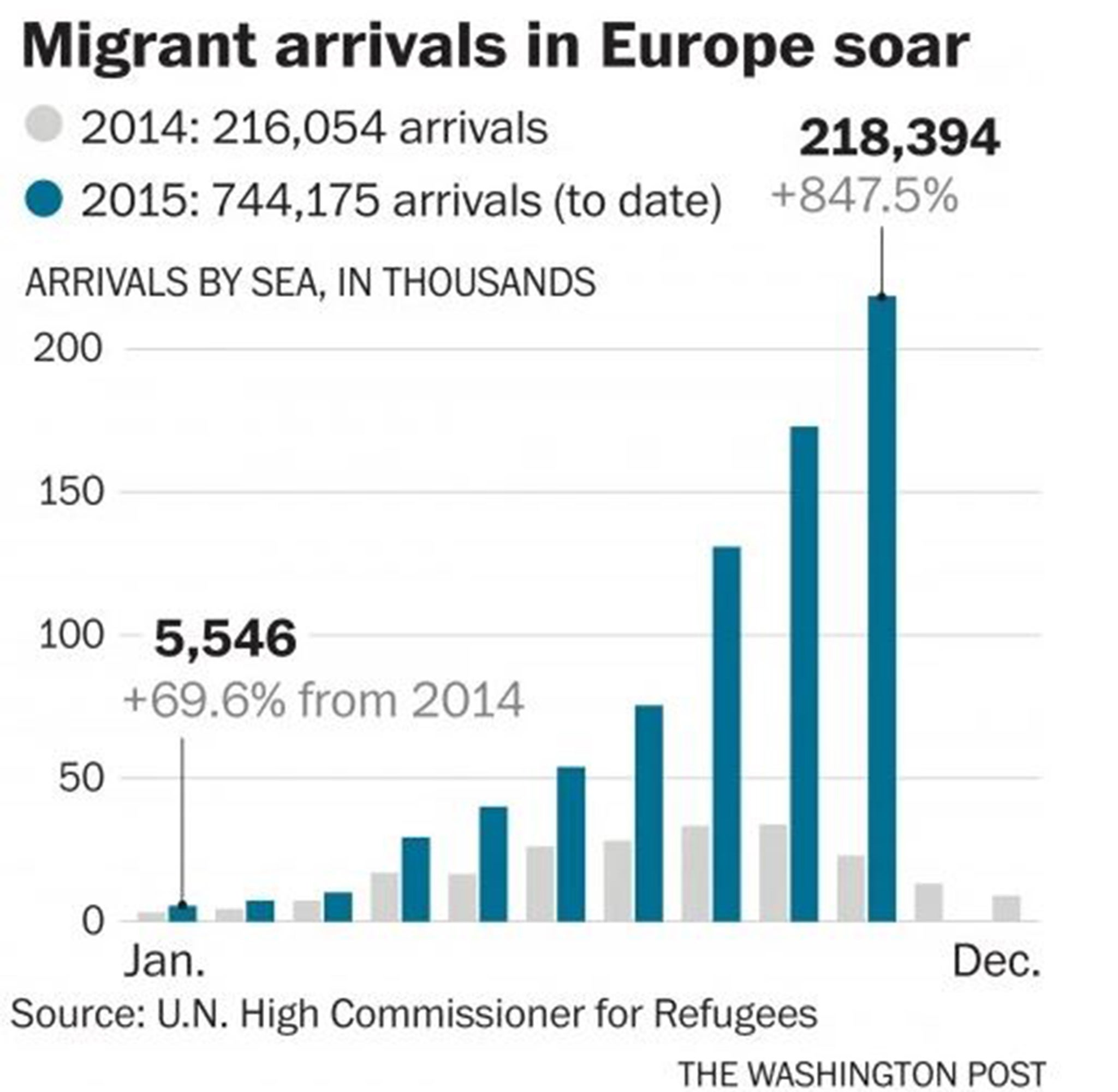

The U.N. refugee agency said Monday that a record 218,394 people crossed the Mediterranean to reach European shores in October — about as many as the total from all of last year. As the numbers rise, officials in countries across central and southeastern Europe are eyeing one another nervously, fearing that a sudden closure of any one border could unleash a domino effect across the region that would leave tens of thousands of people stranded and angry, far from their intended destinations in the continent’s north.

The result would be chaos and violence, said Croatian Interior Minister Ranko Ostojic, who has coordinated his country’s response as more than 300,000 people have crossed through the small coastal nation since mid-September — including 8,400 on Sunday alone.

“You really think you can stop these people without shooting?” Ostojic said. “You’d have to build a wall around Europe if you really wanted to stop these kinds of flows.”

Rather than try to impede the movement of migrants, Croatia has sought to speed it up, arranging trains to ferry people from the Serbian border in the east to the Slovenian border in the west. But the country’s right-wing opposition, which is a slight favorite to win national elections Sunday, has proposed a different solution: a fence.

Slovenia has said it is considering a fence of its own. Foreign Minister Karl Erjavec described that action as “a last resort” but added that he is “very much concerned” that other countries will erect barriers, leaving his tiny Alpine nation shouldering an unsustainable burden. Even now, he said, Slovenia is struggling to cope.

“We cannot go on like this for a long time,” Erjavec said in an e-mailed response to questions. “We have received more than 100,000 migrants in just two weeks. This number represents 5% of our population. Our human, financial and material resources are limited.”

Farther up the trail, Austrian officials said last week that they are planning barriers to better regulate the movement of migrants coming across from Slovenia. They quickly clarified that they have no intention of closing the border. But they also have said they will not be able to leave it open if Germany — the next stop after Austria and for many asylum seekers the final destination — decides it can no longer handle an influx that brought more than a half-million asylum seekers to the country during the first nine months of the year. As her poll numbers fall, calls are growing for Chancellor Angela Merkel to do exactly that.

“Everyone is afraid of the moment when Germany decides it has had enough,” said Igor Tabak, a Croatian security analyst for the Web site Obris.org.

The closure of borders, Tabak said, would not only undermine the principle of free movement at the heart of Europe’s post-Cold War identity, but it also could be deeply destabilizing in the Balkans, where countries that were in conflict with one another less than a generation ago are being forced to cooperate on the biggest challenge to confront the European Union in decades.

Slovenia, Croatia and Serbia have spent weeks trading accusations of mishandling the crisis. Should a right-wing Croatian government opt to close the border with Serbia, Tabak said, the flow would probably shift to Bosnia, an ethnically divided nation that has struggled to hang together since its blood-soaked birth.

“If you have an influx of a large number of migrants into such a fragile system, it’s easy to imagine the local institutions crumbling in Bosnia,” Tabak said.

Ostojic, the Croatian interior minister, said coordination among the regional rivals has improved after an emergency meeting of Balkan nations in Brussels late last month. In recent days, trains have begun to speed migrants through the region as part of a trial program that is expected to be fully rolled out this week.

The system replaces one that officials acknowledge was woefully unsuited to the scale of the crisis. In the first two weeks after Hungary closed its border with Croatia, forcing migrants to reroute through Slovenia, thousands of people slept in the open each night as rain poured and temperatures plummeted.

Slovenia accused Croatia of sending migrants streaming across the border without warning. Croatia charged that Slovenia had failed to ready itself — a point that some Slovenian officials now concede.

“Nobody had foreseen what was going to happen. The country was not prepared,” said Ivan Molan, mayor of Brezice, a handsome Slovenian town of red-tiled roofs and quiet lanes that has borne the brunt of the crisis.

Molan said the new system of moving asylum seekers across borders by train could help to normalize life in a place where up to 10,000 people had been trekking each day through farmers’ fields and driving away the tourists who normally flock to Brezice for a dip at its thermal spas.

But he fears that the Austrians will close their border, trapping frustrated migrants in Slovenia. The country, like others in the Balkans, has no recent history of welcoming refugees from outside the region and has little to offer them. “If that happens, this part of Slovenia will descend into a real crisis,” Molan said.

At the other end of the country — a mere 75 miles to the north — refugees who were awaiting the chance to walk into Austria said they were desperate to leave a place that had brought them only grief.

“I didn’t even know Slovenia existed before I came here,” said Sozdar el-Hassan, a 24-year-old from Damascus who stood pressed against an iron barricade while clutching her 22-month-old daughter. “It’s the smallest country, but it gave us the most problems.”

On a journey that has become a race to beat both winter weather and the prospect of closed borders, Slovenia had badly stalled her family’s progress: They had crossed through five countries in four days, but Slovenia alone took another four.

One night, they slept outside in the mud, with no blankets. For two days, they were housed in a crowded and filthy tent, with heavily armed police barring the exits. Hassan said they were forbidden to leave the tent to visit family members or even to use the toilet.

“I asked one of the police, ‘Are we prisoners here?’ And he responded, ‘For this moment, you’re prisoners,’ ” said Hassan, a cheery and bright-eyed woman who said she learned English by watching Tom Hanks movies. “It was devastating.”

Hassan said she dreams of studying accounting in Germany after her education was cut short by the war in Syria. But as she stood in the cold and rain waiting for the border to be opened, her exhausted daughter screaming in her arms, she conceded that she would settle for falling a little bit short.

“At least I want to get to Austria,” she said. “I just don’t want to stay here.”

Karla Adam in London contributed to this report

Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments