Red faces in Paris as 'destroyed' Cartier-Bresson snaps resurface

Widow of celebrated photographer says negligent French state allowed pictures to be stolen

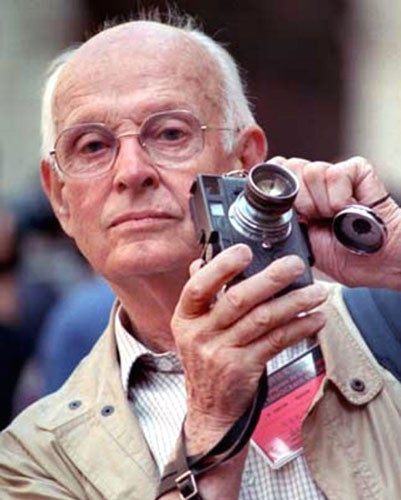

Prints made by the celebrated French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, supposedly destroyed after a flood, are turning up on the market, according to his widow. The allegation is deeply embarrassing to the French government which was given the 551 images by one of the greatest photographic masters in 1955 and 1970.

Some time before 1991, the prints were seriously damaged by flooding while stored in the basement of the contemporary arts centre in Paris. The photographer agreed, reluctantly, that they should be destroyed. In recent years, according to his widow, Martine Francq, batches of prints from this "lost" collection have been turning up on the French art market.

The potential for profit – and official embarrassment – is enormous. Last year an original print, made by Cartier-Bresson himself, fetched $265,000 at auction in New York. "Both sellers and potential buyers should beware," Mme Franck – also a photographer – said yesterday. "It seems that the French state was doubly negligent, first in failing to look after these works and then in failing to destroy them."

The Cartier-Bresson Foundation, set up in 2004 after the photographer's death at the age of 96, has formally requested that the French government confess it did not destroy the damaged prints. The government has refused to make any such admission. It insists that the images turning up for sale on the art market must come from another source.

Prints identified by Cartier-Bresson himself as coming from the government collection first surfaced in 2001. They were offered to an art dealer in Paris by a person who claimed to have found them in a dustbin. Pierre-Marc Richard, an expert who identified the images at the time, told Le Monde: "They were very dirty. It looked as if they had been trampled under foot. They didn't look like photos from an official archive."

After a formal complaint from Cartier-Bresson, the sale was blocked and the incident was hushed up. Mme Francq finally decided to speak out this week after reports that other prints from the "lost" state collection are being offered for sale.

Henri Cartier-Bresson was a pioneer of photo-journalism as an art form. He was a co-founder of the Magnum agency in Paris in 1947 with, amongst others, Robert Capa, David Seymour and William Vandivert.

Cartier-Bresson is best known for his apparently random images of street scenes and his description of photography as the art of the "decisive moment". In 1955, he mounted an exhibition in the Louvre in Paris of 358 images shot in France in the 1930s and Russia, the United States, India and China in the 1940s. These, and another 91 images, were later given to the French state. In 1991, when the Centre National des Arts Contemporain (CNAC) moved its archives from the 16th arrondissement of Paris to La Défense, it was discovered that the prints had been severely damaged by a water leak. (The plumbing of Paris is notoriously bad.)

Cartier-Bresson was invited to view the damage and agreed that the prints should be destroyed. Mme Franck now suspects that at least some of the images were stolen or simply thrown in a dustbin and recovered by persons unknown. She says her husband, before his death, identified some of the images offered for sale in 2001 as prints that he had made solely for the 1955 exhibition.

Claude Allemand-Cosneau, director of the CNAC, told Le Monde that he was "extremely sorry" for Mme Franck but there was no proof that the images now surfacing were from the lost collection.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks