Recognition at last for children who survived the hell of Nazi ghettos

Thousands haunted by Holocaust will receive compensation, 'but it's not about the money'

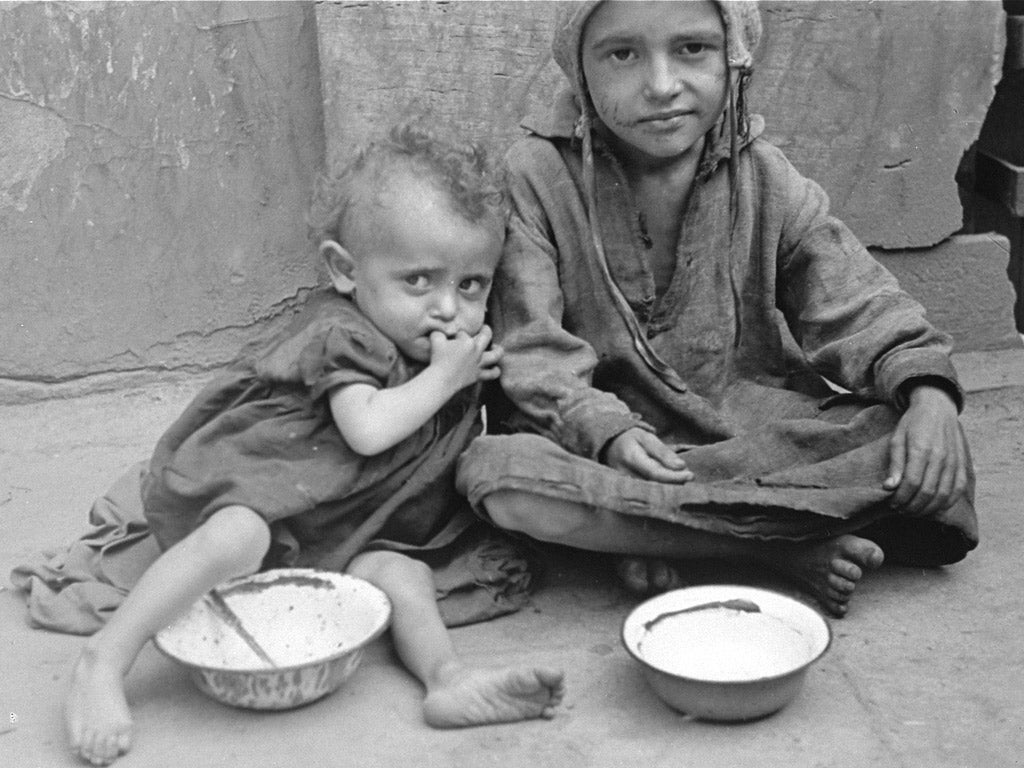

They were among the tens of thousands of Jewish children forced to endure misery, constant fear and starvation in the ghettos of Nazi-occupied Europe during the Second World War. Most of their family perished in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, yet miraculously Otto Herman and Erzsebet Benedek somehow survived.

The brother and sister, now aged 81 and 78 respectively, were freed from the torment of the Budapest ghetto by the Russian army in 1945 and moved to America during the post-war years. But the ordeal that will haunt them for the rest of their days always went unrecognised by the Germany that succeeded Adolf Hitler.

Yesterday however,more than 66 years after the end of the war, the New Yorkers were among about 16,000 Holocaust survivors who will now receive belated financial compensation from Germany under a hard-fought deal reached between the Jewish Claims Conference and officials from Chancellor Angela Merkel's government.

"It is not about money," Greg Schneider, the conference's executive vice-president who brokered the agreement late on Monday, said yesterday. "It's about Germany acknowledging these people's suffering. They are finally getting recognition of the horrors they suffered as children." Mr Herman and Ms Benedek will now receive monthly pensions from the German government amounting to about €240 (£206) each from 1 January.

Speaking from his Brooklyn apartment, next door to his sister's home, Mr Herman told the Associated Press yesterday that the additional pension would "help a lot" financially, but he made clear that it could never compensate for his harrowing wartime experiences.

Mr Schneider said the reparations agreement was reached after Germany agreed to criteria for paying compensation to Holocaust survivors. Previously, victims of Nazi persecution had to provide evidence that they were forced to live in a ghetto, in hiding or under a false identity for a minimum of 18 months in order to qualify for German government compensation. Under the new provisions the period is reduced to 12 months.

Julius Berman, chairman of the claims conference, said that his officials had long emphasised to the German government that it could not "quantify" the suffering of Holocaust survivors. "Living in hiding came with an unimaginable fear," he said. "Discovery would have resulted in the death sentence for any Jew who survived in hiding or by living under a false identity."

The Nazi regime set up more than 1,000 ghettos across Europe. The majority of the predominantly Jewish inmates were deported to the death camps. More than 400,000 Jews were herded into the infamous Warsaw ghetto. Thousands more were incarcerated in similar enclaves in Vilnius, Minsk, Lodz, Odessa and Budapest where they were forced to work while suffering starvation and illness.

In Budapest, many the city's Jews were initially protected by the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who set up safe houses and issued passports. But from late 1944 onwards they were rounded up by the Nazis and herded into a ghetto containing nearly 70,000 men, women and children. Otto Herman was sent to the Budapest ghetto with his sister. He was 14. His sister was only 11.

"I will never forget. Sometimes I don't want to speak because of the memory," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks