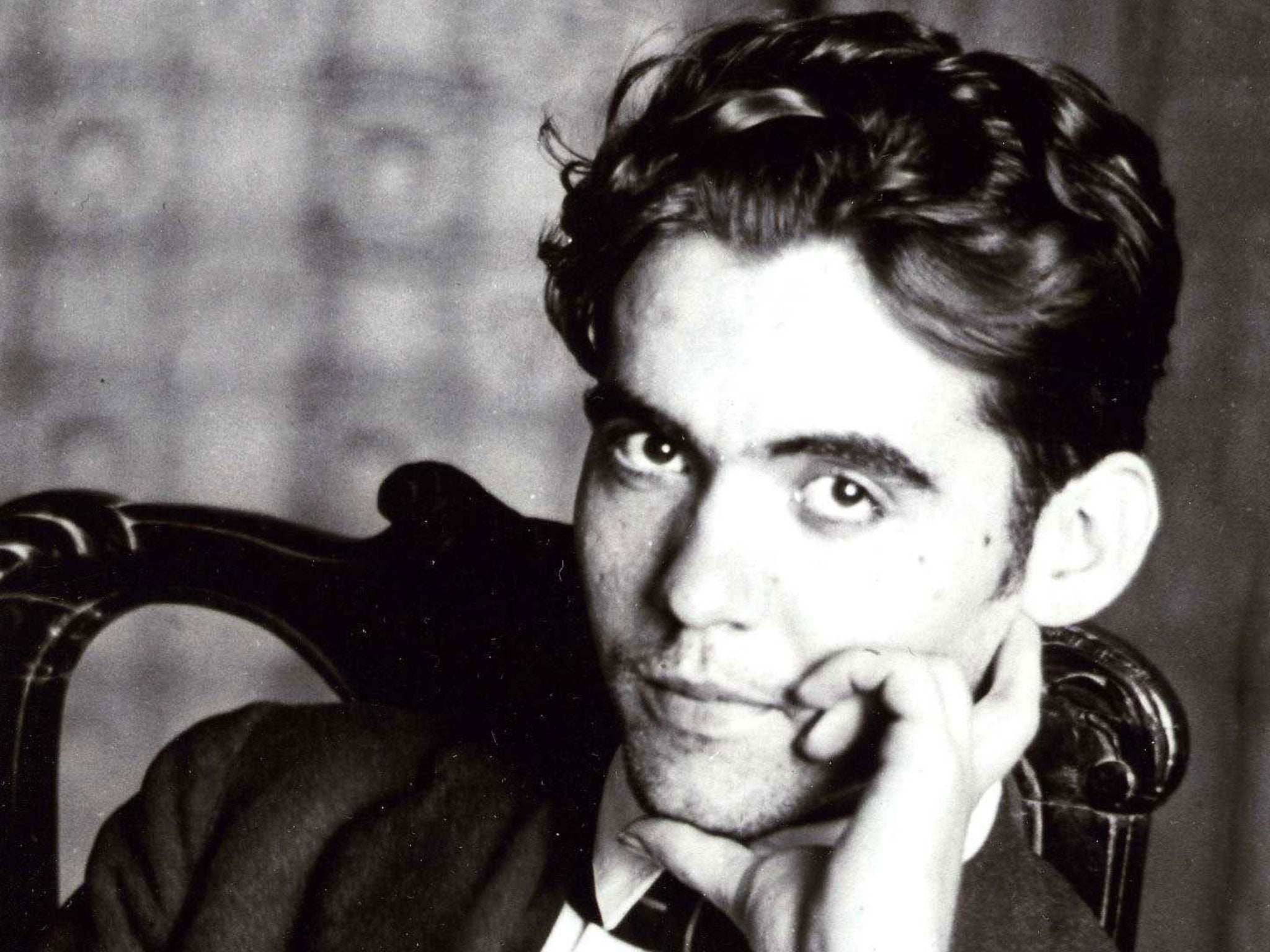

On show after 80 years, the poetry of Federico García Lorca that General Franco couldn't kill

Murdered Spanish poet’s key work to debut at New York exhibition

On 12 July 12, 1936, Spain’s most translated poet and playwright, Federico García Lorca, left the manuscript of one of his key works, Poet In New York, on the desk of his editor José Bergamín in Madrid with a handwritten note on top: “Back Tomorrow”.

But tomorrow never came. Instead of returning Lorca – part of the ‘Generation of ’27’, an avant-garde artists collective that included his friends Salvador Dali and film-maker Luis Bunuel – went home to Granada, where he was murdered five weeks later by General Franco’s death-squads as Spain tore itself apart in its three-year Civil War.

As for the Poet in New York manuscript, it was taken first to Paris then to central America by Bergamín as he and other Republicans went on the run from Franco. But shortly after an initial dual print run in 1940, the manuscript disappeared, with disputes lasting for decades over the accuracy of ensuing published versions.

Now, for the first time, those doubts should evaporate when the 96-page manuscript – located in 2003 when it was sold at Christies to the Federico García Lorca Foundation for £120,000 by an unemployed Mexican actress – finally goes on public view.

As from next Friday, 5 April, the manuscript will form part of the largest-ever North American exhibition of García Lorca’s work, held in New York’s Public Library and also containing drawings, photographs, letter and mementos from Lorca’s six-month spell at Columbia University in 1929-30 such as his guitar and library card. Coinciding with the exhibition, new English and Spanish language versions of Poet In New York are also due to be published.

Sent by his parents to the USA to study English and recover from an unhappy love affair with sculptor Emilio Aladren, Lorca’s Poet in New York harshly criticises modern-day capitalism. It is also what Lorca expert Christopher Maurer told NBC Latino media channel was “an indictment of contemporary civilization and a dark cry of metaphysical loneliness.”

“Lorca’s influence on American poetry cannot be overestimated,” added Susan Bernofsky, director of the Literarary Translation programme at Columbia University’s School of the Arts. “Something about his imagination has proved inspirational for many generations of writers.”

Amongst those North Americans inspired by the author of Blood Wedding, Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba are pop musician and artist Patti Smith, who will give a recital at the exhibition, Canadian folk singer Leonard Cohen, who called his daughter Lorca, and top South American poet Pablo Neruda – together with Lorca, one of the few Hispanic poets with a mass following among English-speaking audiences.

If one of his greatest works will now go on public show in its most complete version to date, the body of García Lorca himself has not been found.

Murdered by a right-wing death squad in the first months of the 1936-39 Civil War, his body is one of hundreds of Republican prisoners in a mass grave in the ravines of Viznar above Granada – and one of tens of thousands who suffered the same fate still lying in roadsides and ditches across Spain, almost 80 years after the war ended.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks