Omens look bleak for Vladimir Putin: Can the president ride out the storm?

As the Russian government raises interest rates to combat falling oil prices and Western sanctions over the Ukraine, Mary Dejevsky wonders how far the rouble will fall and whether the Russian president can ride out the storm

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

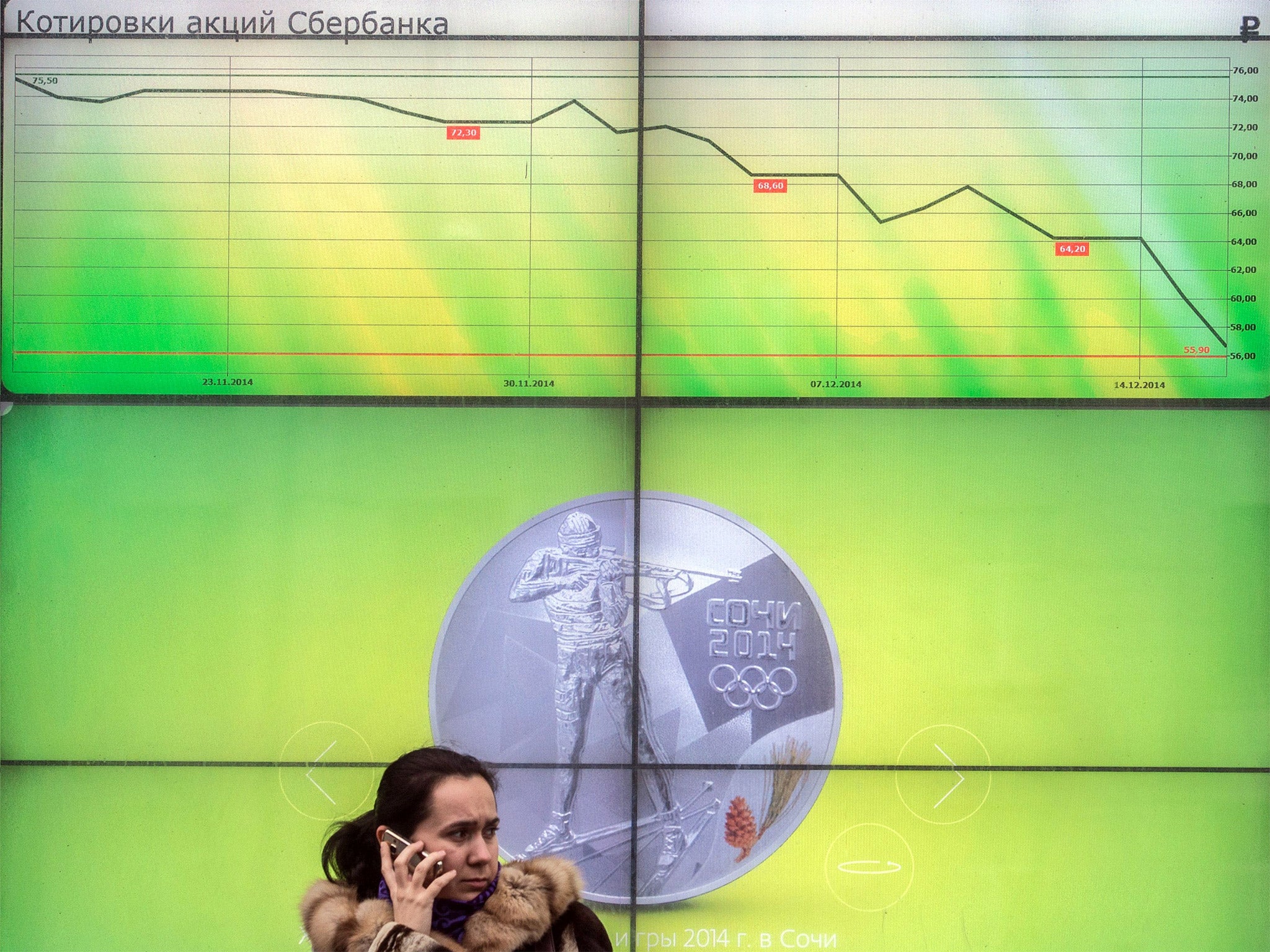

Your support makes all the difference.The raw figures look bad, and they are deteriorating. Experts differ on quite how much of a crisis the Russian economy is in – from the apocalyptic: the country is fast running out of money; it is on the verge of financial collapse and its reserves are not what they appear – to the phlegmatic.

Some of those in the second camp – take out oil and the Russian economy is well-managed, unencumbered by debt, and its foreign currency reserves are sufficient to see the country through another year and probably more – accuse some in the first camp of deliberately talking up the damage to open up, in effect, a third front in the bitter east-west stand-off over Ukraine, credibility being at least half the battle where a state’s finances are concerned. And so far, at least, comparisons with the 1998 currency crisis are in the Kremlin’s favour.

Although Russians can see the value of the rouble decreasing pretty much each day, there has as yet been no run on the banks. In an echo of the past, when payment was often demanded in “hard currency”, however, the government has warned that it is illegal to price goods in any currency than the rouble, and capital flight for 2014 is said to have run at record levels. One explanation might be that those with access to other currencies have already secured their cash by whatever means, while those operating solely in the rouble economy have yet to see any substantial change.

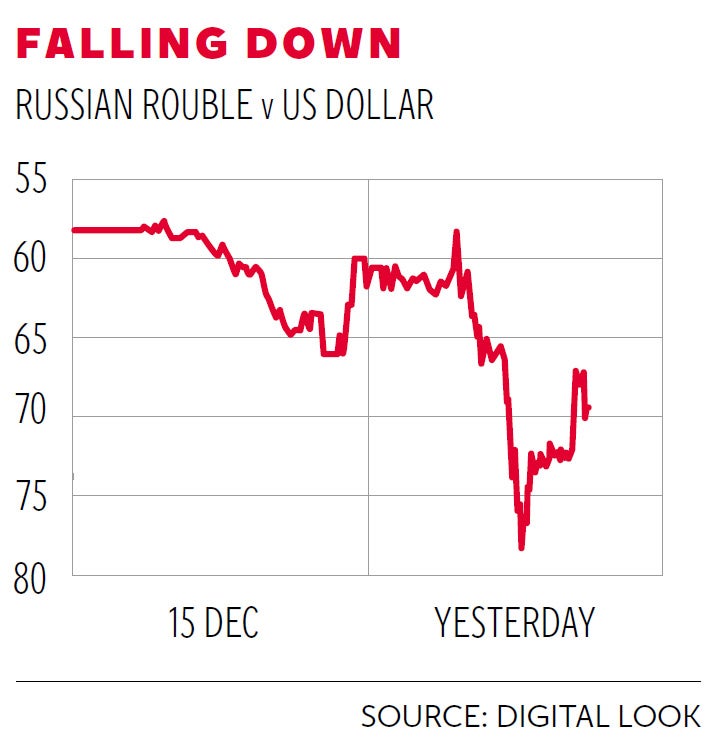

In her first official statement on Monday’s dramatic rise in interest rates, the head of Russia’s Central Bank yesterday defended the move as designed to curb inflation and encourage Russians to deposit more of their roubles in savings accounts. But Elvira Nabiullina, who has headed the bank since last year, said she did not expect the increase to have any immediate effect on the rate of the rouble, which has fallen sharply against the US dollar and other international currencies in recent trading.

On Monday, the Russian currency suffered its sharpest drop for 16 years, falling 10 per cent against the dollar, on rumours, it is said, that the US was preparing a new round of sanctions. Yesterday, the White House said Barack Obama was expected to sign legislation implementing new sanctions by the end of this week.

Analysts say the main reason for the rouble’s demise is the fall in world oil prices, which have slid from above $100 a barrel to $60 in the past six months – oil and gas taxes making up half of all the Russian budget’s revenue. The sanctions imposed by the US and EU in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its interference in eastern Ukraine are seen as an additional factor.

Yesterday, the rouble stabilised. Ms Nabiullina insisted in an interview that the rouble was currently undervalued in relation to the state of the Russian economy overall, but conceded that any return to what might be seen as a more normal rate would take time. Russia, she said, would have to learn to live in the “new reality”.

The rate rise, which is said to have been approved by President Vladimir Putin personally, is the latest and most demonstrative attempt by the Russian authorities to limit the economic damage from the debilitating conjunction of falling oil prices and Western sanctions.

If the government and Central Bank between them can retain public confidence, it is possible that Russia’s exchequer will be able to ride out the crisis. President Putin’s popularity rating remains only a little below the 80-plus per cent approval rating he attained after the annexation of Crimea, and most fundamentals of the Russian economy are seen as sound.

If, however, the sterling devaluation of 1992 and the UK’s enforced departure from the European Exchange Mechanism are seen as any sort of precedent – and there are parallels in the self-reinforcing nature of what is going on – then the omens are not good.

Or would the fall in the rouble – given that a currency is so closely bound up with national self-esteem – lead to a loss of public confidence in Putin that would trigger economic meltdown and a run on the banks. Or would a deepening crisis have the effect of boosting Putin’s stature still further as the protector of the nation in its adversity – and then what if he failed?

There is already whispering about cabals in the Kremlin, with sections of the military pitted against a more peaceable Putin clan – though, again, such reports could reflect wishful Western thinking and desperate attempts to “explain” Russia’s actions in relation to Ukraine.

For the short term, at least, a majority of Russians seem prepared to rally round Putin and join him in blaming Western malevolence for their plight. And if disillusionment set in, and Putin were to lose his popularity or his job, or both, what then?

The greatest danger would be for Western governments to assume that any replacement would be more to their liking. With nationalism in the ascendant, following what Russians see as the “recovery” of Crimea, a new president would need to promise more. Suing for peace would not be an option.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments