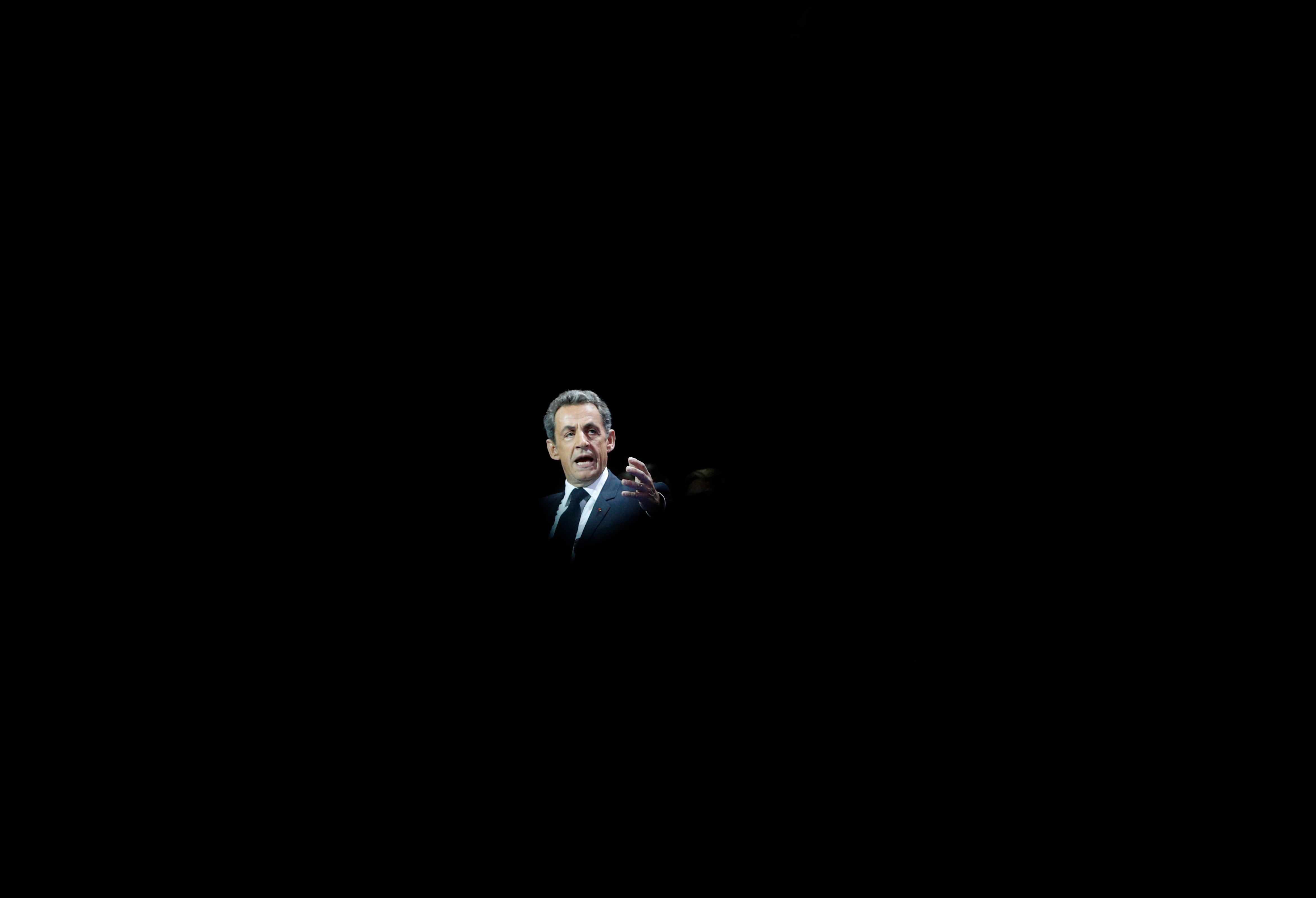

The rise and continued fall of Nicolas Sarkozy

The conviction for corruption completes a disastrous fall from grace for the once French president

President “Bling-Bling” and “The Gallic Thatcher” were Nicolas Sarkozy’s nicknames when he arrived at Windsor Castle on a state visit as a guest of the Queen.

The year was 2008, and France’s newly elected head of state was revelling in his reputation as a radical conservative politician who was ready to break the mould.

Gone were the stuffy conventions – Sarkozy had Carla Bruni, his new supermodel and pop singer wife by his side, and was determined to become an international media celebrity in his own right.

Sarkozy spoke of a “rupture” with the past that would haul his stagnating country into the 21st century as he promoted liberal economics in the forceful manner Margaret Thatcher had done in Britain in the 1980s.

Now, following a disastrous fall from grace, Sarkozy’s political career is all but over – he is a convicted criminal who will now spend many more years trying to stay out of prison.

Sarkozy’s conviction for bribing a judge is particularly humiliating considering his background as a notoriously reactionary interior minister.

As well as appealing his three-year prison sentence for corruption and influence peddling, Sarkozy faces further criminal trials, including over allegations that he accepted millions from the late Libyan dictator, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi.

Sarkozy had initially treated Gaddafi as a firm friend – inviting him to Paris for a state visit of his own in 2007 – but then turning on him by setting up the bloody intervention in Libya in 2011 which directly led to Gaddafi’s murder.

The military adventure is now blamed for turning the north African country into a failed state full of warlords and people smugglers.

It is certainly not what the future president envisaged while growing up in the 17th arrondissement of Paris, and then in the suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine.

Nicolas Sarkozy de Nagy-Bocsa was a classic put-upon small boy who had mighty ambitions.

He was frequently targeted by bullies because of his size – just 5ft 5in in his stacked heels – and also because of his foreign antecedents.

Politics was a way of asserting himself: “What made me who I am now is the sum of all the humiliations suffered during childhood,” he once admitted.

He entered local politics in his teens, and by the time he was 27 had become the mayor of Neuilly.

Sarkozy then virtually hijacked the Union for a Popular Movement – the party created as a vehicle for his one-time mentor Jacques Chirac – and used it to project himself as the future of France.

Deploying the kind of spin first formulated by Blairite strategists in Britain, Sarkozy presented himself as a leader capable of creating a new France.

He promised to revitalise the stagnant French economy, create jobs, and destroy the power of the unions crippling the country with over-generous pension schemes, the thirty-five-hour week, and the other benefits of an all-encompassing welfare state.

In fact, Sarkozy’s grand plans fizzled out completely. His single term of office is best remembered for his glamorous holiday snaps and high spending with Bruni, his third wife.

As soon as he got into power, Sarkozy awarded himself a pay rise of 140 per cent, worth the equivalent of around £210,000 a year, but this sum barely equalled a day’s earnings of the super-rich cronies he surrounded himself with.

Many of them had piled into Fouquet’s, the historic restaurant on the Champs-Elysees, for a celebratory party on his May election day in 2007.

They included multibillionaire friends Bernard Arnault, the head of the LVMH luxury goods empire and the wealthiest man in France, and other industrialists such as Martin Bouygues, and Vincent Bollore.

The first official foreign engagement together for Sarkozy and Bruni was the state visit to Windsor and London.

Its opulence set the tone for their time at the Elysee Palace, as they were compared to Louis XVI and his queen, Marie Antoinette.

Sarkozy was first ordered to rein in his expenses after it emerged that he and Bruni were spending more than £660 a day on flowers.

The Sarkozys were also advised to abandon one annual Bastille Day garden party because they had spent £600,000 on the previous one.

The figures were part of the first state audit of a French leader’s expenditure since Louis XVI, whose outrageous spending was one of the causes of the French Revolution.

When Sarkozy and Bruni decided to refit one of France’s presidential planes, they spent £50,000 on a new bread oven, just so that they could experience the thrill of oven-fresh baguettes at 700mph.

Promising nicknames such the “Gallic Thatcher” certainly all sounded laughable by the time the Sarkozy presidency came to an end in May 2012.

He was replaced by Francois Hollande, a socialist who said he “hated the rich” and who had promised a top income tax rate of 75 per cent.

The Paris home Sarkozy shares with Bruni was raided by fraud squad officers within two days of him losing his presidential immunity from prosecution in 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks