'Last Nazi trial' opens in Munich

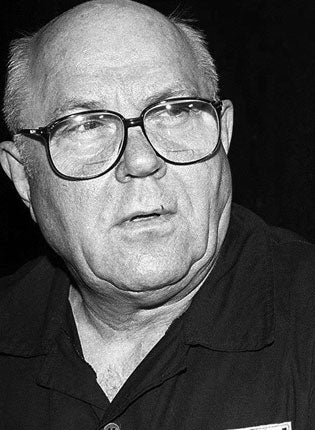

Sixteen years after Israelis acquitted him as falsely identified, a frail John Demjanjuk is back in the dock

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is being billed as the last big Nazi war crimes trial. This morning, a frail, cancer-ridden, 89-year-old Ukrainian with a life expectancy of less than a year will appear in a Munich courtroom to answer for a mass murder so monstrous in scale that it still defies the imagination, 66 years after it took place.

John Demjanjuk, who was only extradited from the US to Germany earlier this year after being pursued by justice for decades, is accused of being one of the feared guards at the Nazi-run Sobibor extermination camp in German-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Between April and June 1943, nearly 30,000 Jews, many of them from Holland, were picked up from their homes in raids and shipped to Poland where all of them were ritually slaughtered in the camp's gas chambers, executed in mass shootings or simply clubbed to death by brutal SS-men specially trained for the job.

German prosecutors have arrived at the death toll from Nazi records detailing the number of Jews who were forced on to 15 train transports from Holland during that period. A total of 29,579 boarded the trains but 1,679 of the passengers died en route in the airless and windowless rail cars into which they were herded like cattle.

Many of the witnesses called to give evidence against Mr Demjanjuk are the surviving children of those murdered in Sobibor in those months. About 30 them will attend today's trial, many of whom said yesterday that they had been plagued for most of their lives by feelings of guilt that they had been able to survive while their parents were slaughtered.

David van Huiden, 78, only escaped being rounded up and shipped to the camp because his parents had told him to take the family's Alsatian dog for a walk in the event of a round up. Mr Van Huiden says he escaped because the Germans took pity on the dog, a German breed. He survived the war hidden by a non-Jewish Dutch family. His mother, stepfather and older sister were dispatched to Sobibor and murdered on 29 June 1943. "My parents were unable to defend themselves," Mr Van Huiden said yesterday. He says he must now do what his parents could not.

Prosecutors will aim to prove that Mr Demjanjuk was genuinely a Sobibor SS guard at the time of the mass murder. Kurt Schrimm, the chief prosecutor in the case, insists that there is no doubt. "For the first time we have found the lists of names of people Demjanjuk personally led into the gas chambers," he said in a pre-trial interview

Mr Demjanjuk insists that he is completely innocent and that the prosecution's case against him is based on mistaken identity. His lawyers say they will contest evidence against him which may have been given under duress. "Some of the witnesses were questioned 30 years ago in what was part of the Soviet Union and possibly under pressure," said Gü Maull, Mr Demjanjuk's lawyer.

Born as Ivan Demjanjuk in the Ukraine in 1920, he joined the Red Army at the beginning of the war and fought until he was captured by invading German forces in 1942. Mr Demjanjuk then claims to have joined an anti-Soviet Russian military unit that was funded by the Nazis and to have fought with the unit until the end of the war. He emigrated to the US as a displaced person in 1952.

But by the early 1980s, Israel became convinced that it had blown Mr Demjanjuk's cover and persuaded the US to extradite him to stand trial on charges that he was in fact "Ivan the Terrible", a notorious Ukrainian guard at the Treblinka death camp who forced Jews into the gas chambers with a sword. But in 1993, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that there was reasonable doubt about whether Mr Demjanjuk was Ivan the Terrible. He was cleared.

In 2002, the US authorities unearthed fresh evidence that Mr Demjanjuk was employed in Nazi death camps. However it was not until last year that German prosecutors came up with evidence sufficiently incriminating to persuade the US to extradite him. Mr Demjanjuk was flown to Germany earlier this year. Prosecutors say one of their key pieces of evidence against him is an SS identity card which shows that he was posted to Sobibor in 1943.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments