Italy's 'Armani of Mozzarella' Giuseppe Mandara arrested over 'contaminated cheese' amid accusations of mafia association

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.UPDATE (31.07.20): We can confirm that all charges against Guiseppe Mandara, as set out in this article, were dropped.

Italian newspapers usually only carry three varieties of headline: “Bufera su…” (egg on the face of …); “Giallo su…” (mystery surrounds…); and “La Lega insorge” (the populist Northern League party is getting its knickers in a twist).

But today a fourth headline – “King of the bufala” – was born, such was the clamour following news that the country’s top mozzarella mogul was in handcuffs, accused of adulterating his prize product.

Bufala means buffalo (which is supposed to supply the milk from which the top cheese is made) but also hoax or fraud –the likely indictments which threaten the cheese king with jail time.

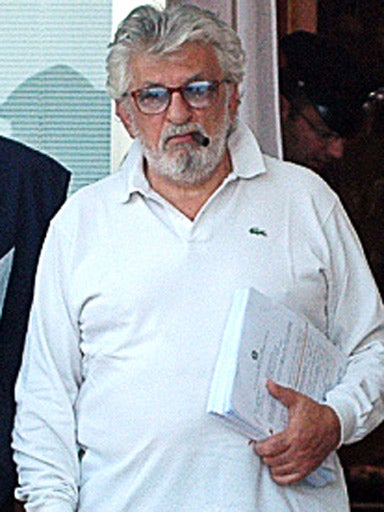

Additional accusations of mafia association, while less shocking to your average Italian, mean that, if he is proved guilty, the sentence for Giuseppe Mandara, who once called himself the "Armani of Mozzarella", could be a lengthy one.

Police held him and three associates after prosecutors decided there was sufficient evidence that he and his company, the Mandara Group, the biggest producer of buffalo mozzarella in Italy, were effectively controlled by the notorious Casalesi clan of the Camorra mafia, which is based in the Caserta province near Naples. They also seized assets worth €100 million.

Investigators say the company conned consumers by mixing ordinary cow milk with the more expensive and creamier buffalo product. Mr Mandara is also accused of labelling batches of ordinary provolone cheese as a more prestigious variety. One of the Italian judiciary’s wire taps even recorded Mr Mandara telling a colleague: “We’ll pretend we’re stupid, then we’ll be OK.”

For many Italians, adulteration of such a key element of their prized cuisine is regarded with horror. Fabio Vassallo, a Naples-born writer, said: “For us it’s the national cheese: it's an institution for both Italians and Neapolitans. In Campania [the region containing Naples] you don't even have to say ‘buffalo mozzarella’ – when you say ‘mozzarella’ it's a given that it's going to be buffalo.”

Perhaps more worrying is the charge that the Mandara business had traded in noxious substances after it was found that up to two tonnes of buffalo mozzarella, which was taken off the market, was contaminated with ceramic residue from a broken machine. The potential seriousness of this incident was underlined by Mr Mandara’s own intercepted comments; he was recorded telling a colleague that if the bits of tiles were swallowed by a small child “there could be a tragedy”.

For its part, Italy’s mighty mozzarella sector, which also exports to the rest of Europe, Japan and the United States, lost little time in trying to avert a financial disaster, amid fears the industry could go udders-up on news of one company’s adulterated cheese. The board of the consortium of buffalo mozzarella producers convened an emergency meeting at which Mr Mandara's membership was rescinded. In a statement, it expressed its “full confidence in the magistrates operation”. It can also point to the obligatory anti-mafia certificate that came into force for association members at the end of last month.

However, Mr Vassallo said: “I'm not surprised about the arrests: in Caserta there are so many dairy industries that obviously some of them must be run by the Camorra – the Caserta area is one of the most corrupt in the country and probably not that scrupulous about production standards.”

Prosecutors’ claims that Mr Mandara had received a bailout from the mafia when he was in financial trouble in the 1980s also serve to underline concerns that, in times of economic hardship and credit crunches, organised crime is always ready to step in with offers of assistance that many people or businesses might find hard to refuse.

Nonetheless, Michele Buonomo, the president of the Campania division of the national environmental group Legambiente, was upbeat following the arrest of Mr Mandara. “I applaud the magistrates,” he said. “The criminals of the buffalo mozzarella don’t belong in the land of mozzarella DOP [Denominazone di Origine Protetta or protected name of origin label that is supposed to guarantee the quality of buffalo mozzarella]… The investigations and the rigorousness of the checks guarantee the health of the public.”

And past experience suggest that public health really does need protecting in the context of mozzarella. In 2008, toxic dioxins were detected in the buffalo milk of some local dairies. The carcinogenic chemicals were thought to be present in the soil – and the grass eaten by the buffalo – as a result of the illegal dumping of toxic waste, an activity that makes the Camorra hundreds of millions of euros a year. Later, in 2010, Italian authorities had to issue a Europe-wide alert over possible contamination of mozzarella after balls of the cheese turned a worrying blue colour.

Nor are the problems limited to mozzarella. Last December, a report by the trade groups Unaprol, Coldiretti and Symbola warned that many "extra-virgin" olive oils on sale in Italy were adulterated rip-offs containing cheap oils obtained from any of half a dozen Mediterranean or North African countries, with many contaminated by rancid and mouldy ingredients. It said that four out of five bottles of extra-virgin "Italian" olive oil were actually blended with cheap foreign oil in a five-billion euro (£4.1 billion) a year scam. Warnings have previously surfaced on other key staples of the Italy's celebrated cuisine, including claims that supposedly fine wines are really cheap and nasty imitations from Romania, Poland and even Bolivia.

It’s tempting to suggest there’s something quintessentially Italian about these “Agrimafia” scandals with their mixture of the sublime (southern Italian food) and the (ethically) ridiculous willingness to debase it for a quick buck.

Mr Vassallo is not sure. “I do know there is easy money to be made. And you can find yourself part of a corrupt system in which it is difficult or impossible to say 'no'," he said. On a positive note, though, he says fans of Italian food can always look to the producers of undisputed quality such as Vannulo. “Go to places like this and your faith in real mozzarella is restored."

And eat a Naples pizza or a caprese salad with fresh quality mozzarella and it's easy to see what all the fuss is about.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments