How a Jewish woman survived pregnancy in a Nazi concentration camp to give birth to her son

During her time at Leipzig-Schönefeld, Fela Herling did everything in her power to hide her pregnancy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was shortly before Rosh Hashanah when I first learned of Simon Herling’s miraculous and triumphant story. Simon came to me by way of Joseph Berger, the recently retired New York Times columnist and author, who is a childhood friend of his. All I knew at that point was that there was an article in Der Tog (The Day), a Yiddish newspaper published in New York from 1914-1971 (that also merged with other Yidish newspapers during its nearly 60-year-long run, becoming Der Tog-Morgen Zshurnal/The Day-Jewish Journal by the 1950s), which related the story of his friend’s birth in a World War II, Nazi concentration camp, all the way up to his Bar Mitzvah.

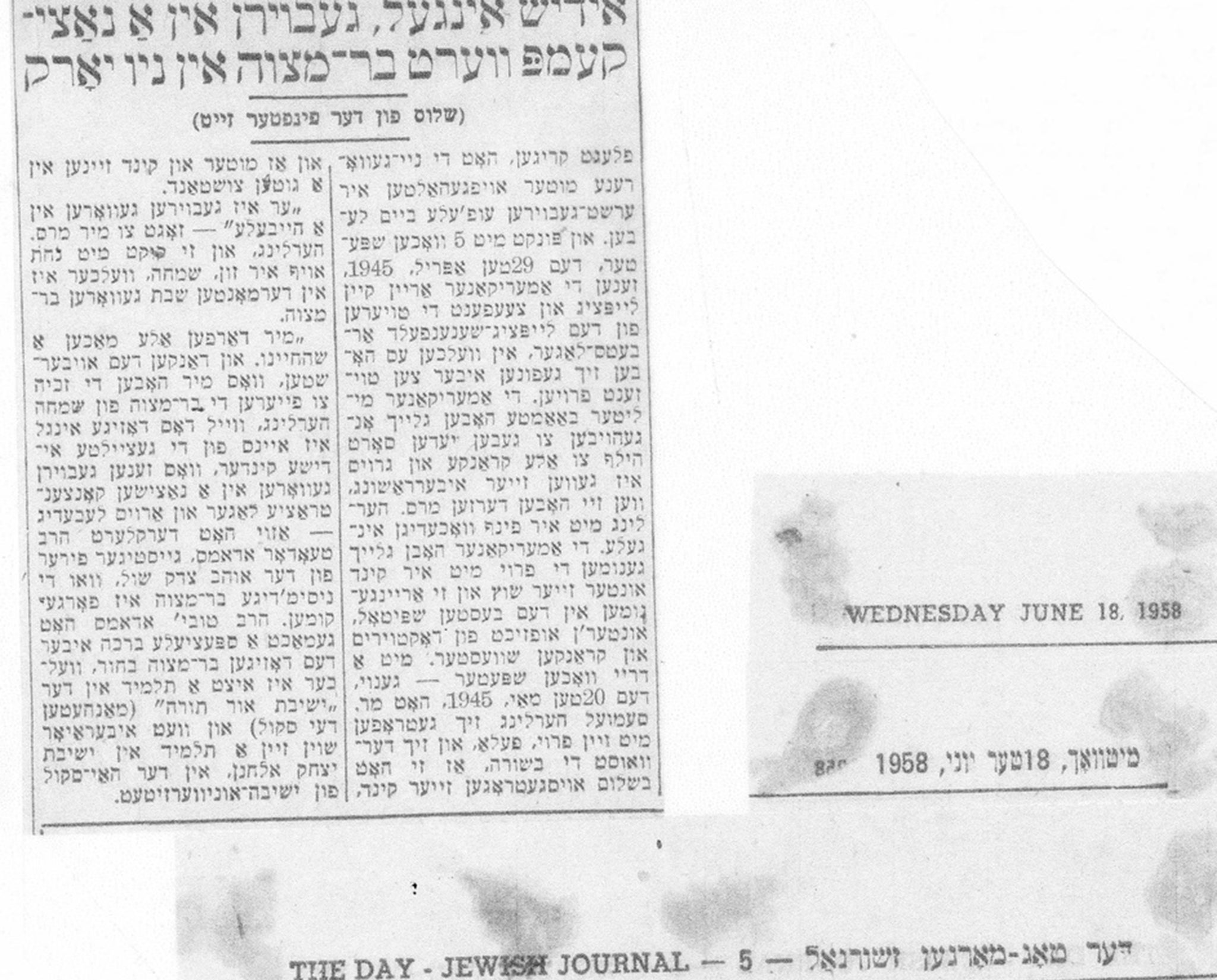

When I heard the part about being born in a concentration camp, I was particularly eager to learn more of Simon’s story and agreed, shortly thereafter, to translate the article. After all, how many children were born in concentration camps and actually lived to see the light of day?! My curiosity was altogether piqued. The article, “Jewish Boy, Born in a Nazi Camp, Becomes Bar Mitzvah in New York” (Wed., June 18, 1958) written by Asher Penn, relates how Simon’s mother, Fela Herling (Warsaw, Poland, c. 1915-New York, 1961) managed to carry him to full-term and deliver him in peace while spending most of those 9 months in the Leipzig-Schönefeld labor camp. Not only that, but Mrs. Herling herself clearly lived to tell of this miraculous feat, as did her husband, Sam or Shmuel (Suchedniów, Poland, c. 1910-New York, 1991).

Up until mid-1944, husband and wife were in the same camp, known as Skarżysko-Kamienna. They had been deported there in September 1942 from the town of Suchedniów, next to Kielce. At that time, the town was made “Judenrein,” and a large percentage of the Jewish community was deported to Treblinka. Among those deported – never to be seen again – were Simon’s four-year-old sister and grandmother. In mid-1944, the Herling couple was separated, with Sam being sent to Buchenwald, and Fela to Leipzig-Schönefeld, a sub-camp of Buchenwald. Shortly before this separation, Fela revealed to her husband that she was pregnant – something that was considered the “kiss of death” for Jewish women incarcerated under the Third Reich. At their parting, the two had no idea whether they would ever see one another again.

From early-on during her time in the Leipzig-Schönefeld women’s camp, Fela did everything in her power to cover up her expanding stomach. This meant seeking out the broadest female prisoner clothing that she was able to get, gathering together several rags, and binding them together around her body. According to the article, “she wore those belts around her person, until her body began to reach the natural fullness that comes from pregnancy.”

Among the various forms of hard labor that Fela was forced to perform during this period were schlepping heavy wagons loaded up with metal rails for a significant distance; carrying heavy sacks with potatoes and beets for an entire day, over an area of three blocks; and carrying down every sack that weighed around 250 pounds, into a cellar. In addition, Fela worked several months in a German ammunition factory, which entailed very long and strenuous hours of work. At one point, when she was already heavily pregnant, she fell asleep on the job – due to sheer exhaustion – and as a result, was savagely beaten with a whip.

Shortly thereafter, news spread throughout the camp that a woman had given birth to a child, which filled Fela with a sense of hope. (Subsequently, it was learned that three women – including Fela Herling – safely delivered infants in that camp, and that all survived.) The consequence of this event; however, which enraged the Nazis, was that the camp’s S.S. officials lined up all the women and told them to confess, if any one of them was pregnant, lest she cause the other women in her block to be severely punished. Upon hearing this, Fela stepped forward, publicly revealing that which she had kept so well-hidden for so long. At this point, she was already beyond the eighth month. The immediate sentence was deportation to be gassed.

But this was already the beginning of 1945; the Germans were losing the war, they were running low on oil and other basic articles of necessity, and were short on vehicles. In addition, they must surely have heard the talk that was already circulating about punishments to be meted out after World War II against the perpetrators of war crimes. Thus, the sheer timing of her pregnancy – quite late in the war – was likely one of the factors that enabled Fela Herling and her son to survive. Had she been pregnant earlier on while serving in a concentration camp, the likelihood that she and her unborn child would have survived the war were nearly impossible.

Yet perhaps the fact that she was living not only for herself, but also for her unborn child, gave Fela the fortitude and stamina to persevere during even the hardest of times. In her words, as quoted in the article: “But this child of mine brought me good luck from the [very] first moment on, even when he was not yet born.”

Instead of being sent for extermination, Fela was allowed – in the nick of time – to remain working in the camp, where she ultimately gave birth on March 23, 1945 to Simon (or Simcha, as he is called in the article). According to Fela, the delivery was swift and easy. Even before the woman who was supposed to be her midwife had fully prepared herself for the delivery, the newly born child was lying there, right alongside his mother.

The American Army liberated the Leipzig-Schönefeld camp on April 29, 1945, finding over 10,000 incarcerated women there. Among those were Fela Herling and her now 5-week-old son – both undernourished – who were sent for immediate medical attention to a hospital, where they were tended to by doctors and nurses. And only a few weeks later, on May 20, 1945, Sam Herling was reunited with his wife, whom he had learned, had given birth to their son, Simcha, while incarcerated in a concentration camp.

Returning to the article in which this miraculous account of survival and triumph was described, this piece was published on the occasion of Simon’s Bar Mitzvah, held in New York City, at Cong. Ohab Zedek, the preceding Saturday [or Sabbath]. The rabbi at the time, Rabbi Theodore [or Tovia] Adams (1915-1984), aptly remarked at the occasion that: “We must all make a Shehechyanu [i.e., a blessing of praise] and thank the Almighty that we have the merit to celebrate the Bar Mitzvah of Simcha Herling; because this is one of the few Jewish children to be born in a Nazi concentration camp and to emerge alive.” Indeed, this is one of the most amazing stories of wartime survival that I have ever read, and I have read and heard – firsthand – a great many such stories.

In speaking with Simon since translating that powerful article, I learned that he had discovered new details about his own history, which he had never before heard from either of his parents, both of whom are now deceased (his mother having died at the young age of 46, when he was only 16). For example, when I asked him whether he knew what had happened to the other women who had given birth to surviving children in the Leipzig-Schönefeld camp during the war, he replied that this was the first time he had ever heard of this.

As Simon conveyed, he did not question his parents much about their wartime experiences while growing up, out of sensitivity for their feelings, and because he did not want to cause them any undue pain, simply for the sake of fulfilling his own curiosity. Thus, only through reading my translation of his article – something that he had put off having done for several decades – had he come to know of the other women who had given birth to surviving children in the Leipzig-Schönefeld camp during the war, or the details surrounding his mother’s incarceration and pregnancy. In his overall estimate, Simon is definitely glad that he learned all that he did from my translation, which ultimately provided him with some pleasant surprises that had eluded him for many years.

If any of our readers has any information about the other children mentioned in this article, who were also born in the Leipzig Schönefeld concentration camp, please contact Rivka Schiller by emailing: rivka@rivkasyiddish.com.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments