Greece crisis: Nation on the brink after creditors refuse to extend bailout deadline

Alexis Tsipras has called for a referendum by the Greek people on the bailout

Greece has been pushed closer to an exit from the eurozone after its creditors ruled out an extension to its bailout programme which is set to expire on Tuesday night.

The country is in uncharted waters. With its financial coffers bare, it is entirely reliant on money from its creditors to pay its debts, and a €1.6m (£1.1m) payment to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is due on Tuesday. Without being able to service its debts, there are fears that it will have to leave the 19-member eurozone and exit the euro.

The sense of a possible disaster was strong as eurozone finance ministers met to try to secure a deal with Greece. In a statement after talks in Brussels, the group said: “Regrettably, despite efforts at all levels and full support of the Eurogroup, this proposal has been rejected by the Greek authorities who broke off the programme negotiations late on 26 June unilaterally.

“The Eurogroup recalls the significant financial transfers and support provided to Greece over the last years. The Eurogroup has been open until the very last moment to further support the Greek people through a continued growth-oriented programme.”

Jeroen Dijsselbloem, the president of the Eurogroup of finance ministers for the currency zone, expressed his regret at the move. The ministers had been surprised by a call by Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras for a referendum by the Greek people on the bailout – which is provisionally set for 5 July, something which appeared to make reaching a deal on Saturday almost impossible. The Greek parliament was due to vote on Saturday night on whether the referendum would take place.

The Dutch Finance minister said of the decision by Mr Tsipras: “I am very disappointed. After our last meeting, the door on our side was still open, but that door has closed on the Greek side.”

The Eurogroup ministers were still meeting on Saturday, without Greek representatives in the room, to decide how to proceed and “prepare for what’s needed to ensure the stability of eurozone remains at its high level”. Upon leaving the meeting, Greek Finance minister Yanis Varoufakis called it a “sad day for Europe”.

Mr Dijsselbloem reiterated his concern over the gap between the end of the deal and the referendum, saying: “How does the Greek government think that it will survive and deal with its problems in that period? I do not know.”

The European Central Bank (ECB), which has been providing Greece with the liquidity needed to keep its banks and financial system afloat, was also meeting to decide its next move.

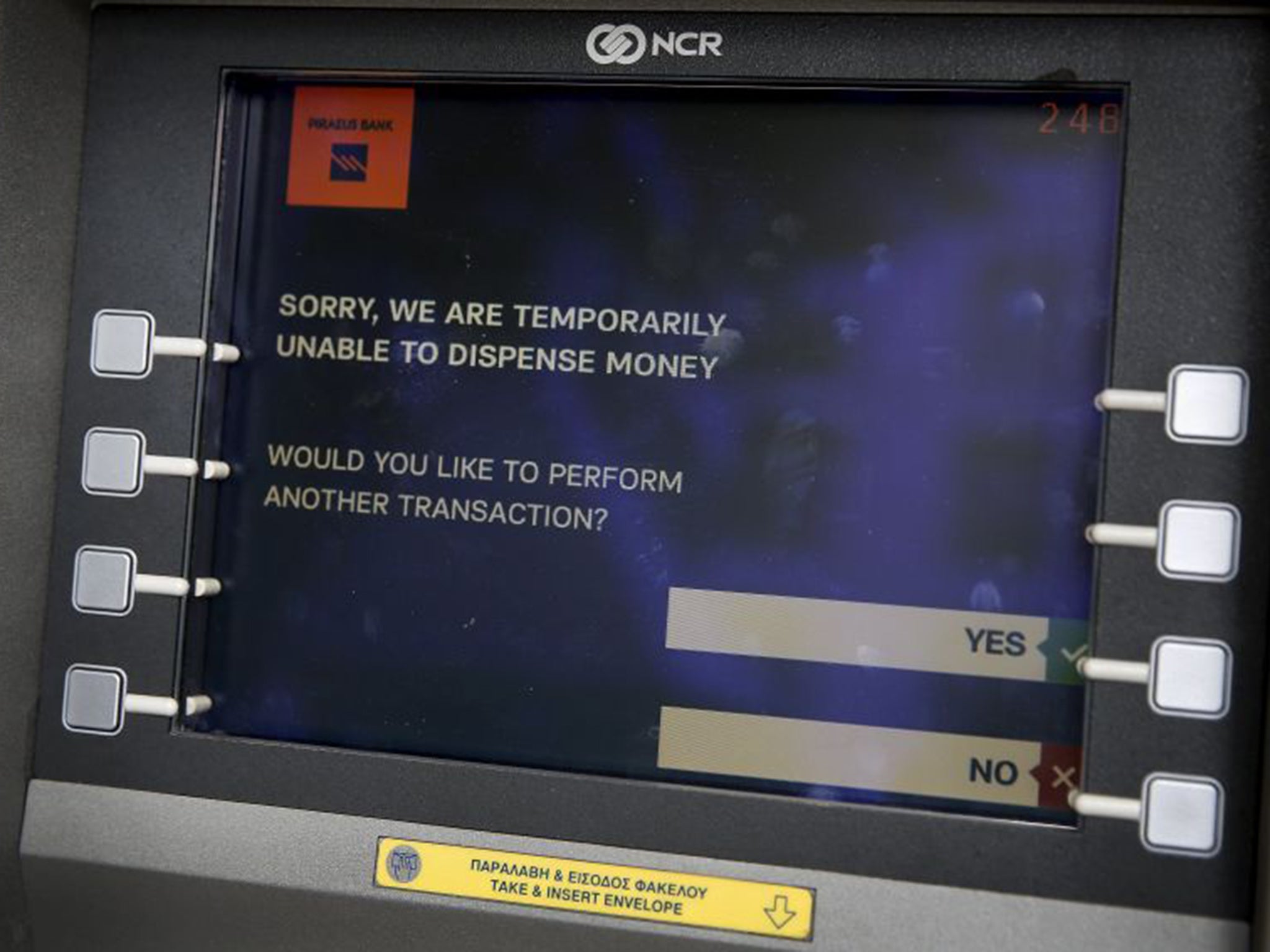

That meeting came as Greeks lined up across Athens to take money out of banks. “Is any cash left?” a pensioner asked a young lady who was unable to get cash from a ATM in the central Pangrati district. Dozens of Greeks crowded outside the bank waiting to see whether it still dispensed cash. “No, nothing. They must have removed it all.”

Mr Tsipras announced the referendum in a dramatic address to the nation late on Friday. In the hours following the announcement of the referendum, people braved the rain and started forming queues outside several ATMs, lasting well until 3am.

“We must have money to shop. We really don’t know what will happen tomorrow,” shouted a concerned cash saver. Local reports suggested that ATMs inside Parliament had been depleted by 2.30pm local time. But the queues weren’t formed only by concerned savers. Pensioners and their families had been queuing to withdraw their pensions which were coming due at the end of the month.

“We’re just rushing to get out money which comes in at the end of the month,” said a retired state worker who refused to give his name; he had served at the finance ministry for years. “I only have €100 in my pocket, don’t really need more. There’s no reason to panic – nothing much can change in a country that has been poor for the past five years,” he said.

A huge banner was unfurled and placed on the “white tower” landmark in Thessaloniki, the second biggest city of Greece. “People of Europe rise up and clash with austerity – no to austerity, no to fear,” the banner read. Meanwhile, social media was buzzing with activity over the referendum. “We vote ‘no’ to the referendum of the 5th of July,” said a call on Facebook. By Saturday afternoon, more than 20,000 users had already signed up to the call.

But not all Greeks welcomed the news of a referendum with enthusiasm. In a gift shop a few yards down from the bank, a couple were shopping for a wallet, trying to decide between two, one having “London” emblazoned on it. “No, don’t get that one – the UK isn’t in the euro and it’ll be bad luck,” said the husband.

Discussion in the shop revolved around the referendum, and the shop owner’s anger was palpable. “I’m angry [at this government]. The referendum is an offence to the Greek voter,” said Francesca Papanika. “People need time and proper information to reflect on this referendum and have a real understanding of the ramifications involved in a no or a yes.”

Ms Papanika points to the UK, which has several months to decide on whether it wants to continue with its EU membership, as opposed to the Greeks who have only seven days. Ms Papanika, who was born in Germany and studied in French, feels her identity is fundamentally European. Although her income dropped by 60 per cent over the crisis years, she is still committed to remaining in the euro.

“We’re in Europe by nature but also because of our geographical position. No one can take that from us.” She is worried about what the drachma could represent for the country and even her business – warning how a return to an undervalued national currency will wipe out small businesses like hers.

Her partner, Eleni Christodoulaki, agreed. “Of course we’re European. The entire question is simply ridiculous,” she said. “Measures will have to be implemented, irrespective of whether we’re in Europe or not, because we must deal with our fiscal and debt problems.”

Yiannis and his wife queuing outside a bank said he was withdrawing enough money to last the coming weeks. “Finally, the people are asked to vote,” he said. “It will be no from me, because Greeks are asked to decide between death and death by Europe. I’d rather die by my own choice in my own country, with fellow Greeks, rather than have someone else decide my fate.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks