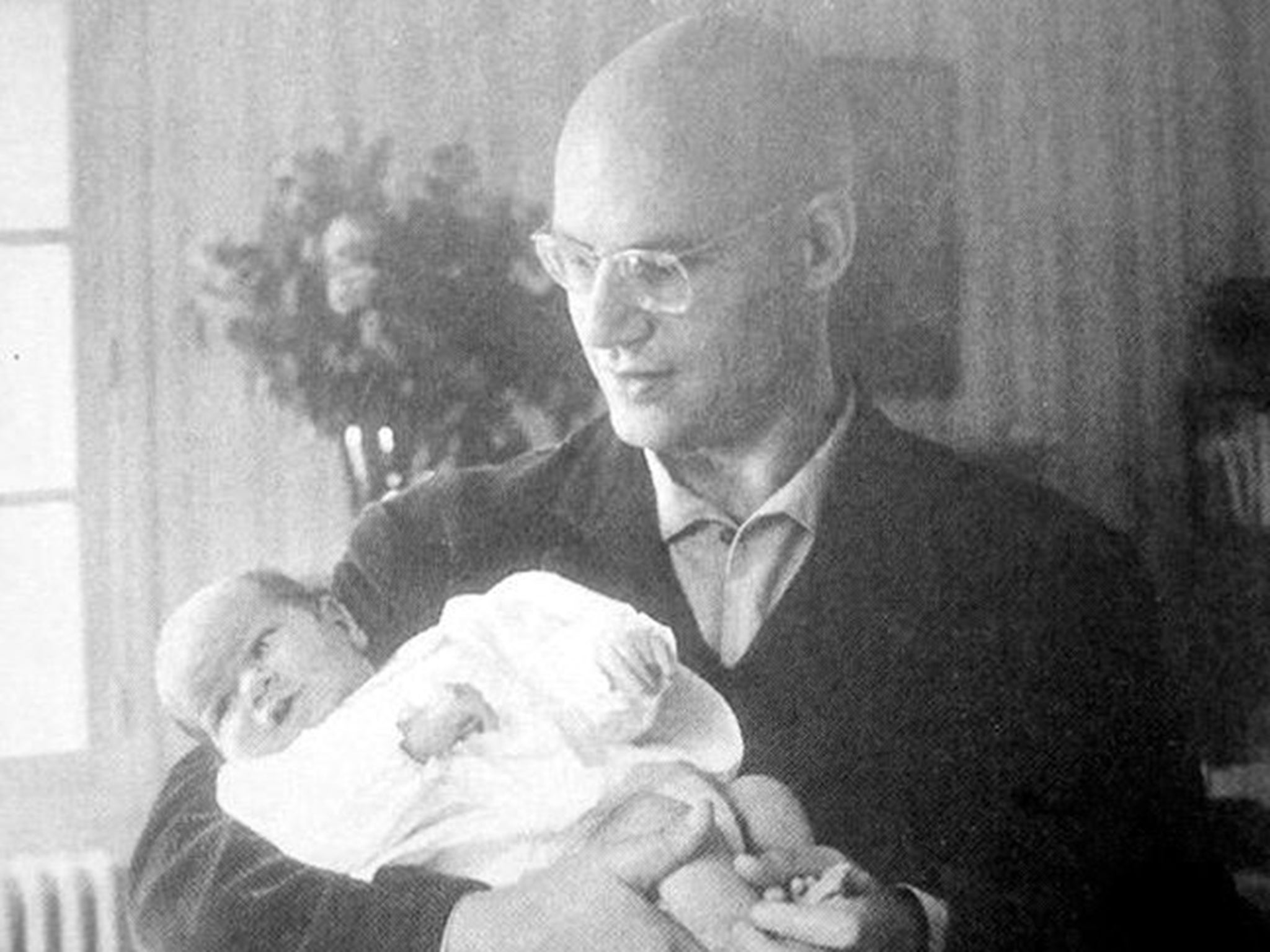

Greatest mathematician of the 20th century and the most important scientific mind you've never heard of: Alexander Grothendieck dies aged 86

Grothendieck lived in his later years as a reclusive farmer and ecologist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alexander Grothendieck was probably the most important scientific mind that you never heard of. He died on Thursday, aged 86, after living as a recluse for over two decades in a small village in the Pyrenees.

Mr Grothendieck, born in Germany, and for a long time stateless, was naturalised French in 1971. He is regarded as the greatest mathematician of the 20th century – someone who transformed thinking about spaces and numbers by his work in the field of algebraic geometry.

The implications of his work are still reverberating through the world of mathematics today, long after he officially abandoned the field to become a subsistence farmer and ardent pacifist and ecologist.

In recent years, he has become a mythic figure to the radical green movement. His unpublished autobiography, Récoltes et Semailles (“Harvests and Sowing”), has been posted on the internet.

Mr Grothendieck’s death will precipitate a scramble to get hold of 20,000 unseen pages of his mathematical works which are held at the University of Montpellier in southern France. Many years ago Mr Grothendieck ordered this archive – and all his other unpublished work – to be destroyed after his death. This instruction may have been rescinded and is, in any case, unlikely to be obeyed.

Grothiendieck was awarded two of world’s most prestigious mathematics prizes – the Fields medal in 1966 and the Crafoord prize in 1988. He accepted, but refused to collect, the first because the ceremony was in Moscow and he detested the Soviet Union. He refused the Crafoord prize - worth $250,000 – altogether.

In a long letter of explanation to Le Monde in 1988, he said that he did not need the money. He also said that science, as then conceived, would be overturned by “a total destruction of civilization… without historical precedent”.

In the same year he told an American journalist: “I’m not a mathematician any more… I now devote my days to the transcription of my dreams.”

Three years later, Mr Grothendieck – already something of a recluse – moved to Lasserre, a village in the Pyrenees, and refused to see visitors, including his family.

He was married three times and had several children. He died in hospital at Saint-Girons in the Ariège department.

Mr Grothendieck was born in Berlin on 28 March 1928. His father, Sascha Schapiro, a Russian Jew, and his mother, Hanka Grothendieck, a radical journalist, left Germany for France in 1933.

His father was deported by the pro-Nazi Vichy regime in 1942 and died in Auschwitz. Alexander and his mother survived the war in an internment camp in the south of France.

Soon after the war he studied maths at the University of Montpellier. He was recommended as a graduate student to two celebrated French mathematicians, Laurent Schwartz and Jean Dieudonné. They gave him a list of 14 unsolved problems and asked him to use one as the basis of his research for years to come. He returned a few months later with the solution to all 14.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments