German elections: what to watch and what could happen next?

For the first time in post-war history there is no incumbent in the running and three candidates with realistic chances of winning; the race is thus truly wide open, writes Erik Kirschbaum in Berlin

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Seen from abroad, post-war elections in Germany have tended to be a bit on the dull side.

In many ways it reflects the country’s tacit desire to be as stable, ordinary and inconspicuous as possible after the turmoil of the 1930s and 1940s – years most Germans yearn to forget. Hence, the conservative Christian Democrats have ruled the giant nation in the heart of Europe quietly and cautiously for most of the past seven decades.

But despite Germany’s natural aversion to changing leaders, Sunday’s 20th national election since 1949 could actually be one worth watching for a variety of reasons – especially as Germany is Europe’s most powerful economy and the undisputed leader for much of what happens on the continent.

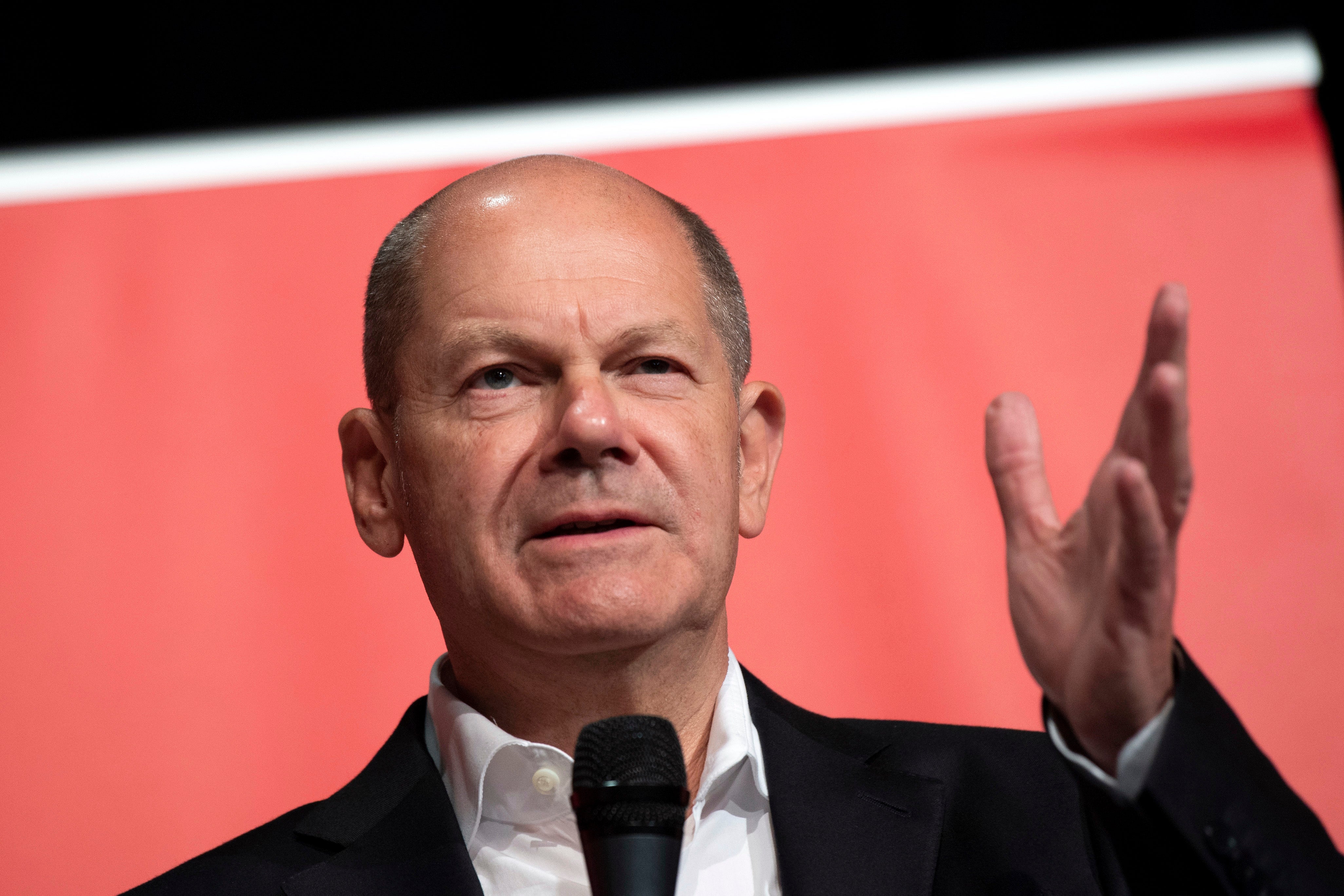

For the first time in post-war history there is no incumbent in the running and three candidates with realistic chances of winning; the race is thus truly wide open – the next chancellor could be either Olaf Scholz from the centre-left Social Democrats, Armin Laschet from the centre-right Christian Democrats or even Annalena Baerbock from the Greens. All three have been atop the polls for several weeks at a time since May.

This will be the first post-Merkel election, and no one has any clue really how it will all end up

Germany has never ever had a ‘throw-the-bums-out’ election and has had only had eight mostly long-serving leaders over the past 72 years – compared with an eye-popping total in Italy of 30 in the same time period at the other extreme. There have been 14 American presidents and 15 UK prime ministers during that period. Epitomising that desire for political stability, just three of Germany’s conservative chancellors ruled for an incredible total of 46 years: Konrad Adenauer, Helmut Kohl and Angela Merkel. Never before did an officeholder leave voluntarily – until Merkel decided to bow out now at 67 instead of facing a defeat at the polls or fall victim to an inner-party rival as all seven of her predecessors.

Adding to the electoral buzz in the air in Berlin this week, opinion polls have been narrowing steadily towards the statistical margin-of-error gap of two percentage points after the voter surveys were especially volatile this spring and summer – the three leading parties have each taken ephemeral turns as frontrunners over the last few months.

There are also more alternative coalition possibilities this year – at least five of which are listed below – than ever before. It thus seems increasingly likely that that an awkward three-party government made up of at least one unwanted bedfellow will be the outcome, also for the first time. It could take at least a month of coalition negotiations – or maybe twice as long – before Merkel can turn over the keys to her successor.

“This will be the first post-Merkel election, and no one has any clue really how it will all end up,” said Thomas Jaeger, a political scientist at Cologne University, in an interview with The Independent. “There are also so many unanswered questions this time around and major issues of the day have been ignored – especially in foreign policy – such as how are Germany and Europe going to be positioned in the worsening China-USA tension as well as what’s going to happen with the European Union.”

Instead, the focus of the campaign has been inward-looking on domestic issues – such as whether or not to raise the minimum wage to €12 an hour or whether Germany should introduce a speed limit on its famous speed-limit-free motorways as a small step towards reducing CO2 emissions. The dominant issue of the past 18 months, the Covid-19 pandemic, has all but disappeared from the front pages for the time being – an uncanny lull that will likely erupt again soon in a country with a vaccination rate of just 63% of those 18 and older.

While the climate crisis and fighting CO2 emissions has figured as the top issue for most German voters in surveys, the three leading parties obfuscated – unable to present compelling or even coherent answers while arguing about carbon pricing, rising petrol prices and whether coal turning plants should be shut down before 2038.

Scholz has gone out of his way to run as the masculine version of Merkel

The lingering Covid-19 pandemic continues to claim lives and open ominous fissures in the country. It also continues to wreak havoc with the economy, yet it was also largely overlooked during the hot phase of the final eight weeks of the campaign, with none of the candidates eager to tackle such a loser topic.

The SPD holds a narrowing two percentage point lead – 25% to 23% – over the Christian Democrats in the polls and are also ahead of the slumping Greens on 16.5%. In early July the situation was reversed, with the Christian Democrats far ahead on 29% compared with 19% for the Greens and just 16% for the SPD. SPD candidate Scholz’s comeback is more due to the series of terrible blunders made by his rivals than anything he has accomplished himself. He has nevertheless rebranded himself as a safe pair of hands and the natural heir to the still-popular Merkel – despite the small fact that he’s from the other party.

“Scholz has gone out of his way to run as the masculine version of Merkel,” one senior government official in Berlin said with admiration of his makeover in an interview, noting that the finance minister and former mayor of Germany’s second city, Hamburg, had even flashed the famous Merkel diamond-shaped hand gesture in tongue-in-cheek fashion for a Munich newspaper photo series. “It’s all kind of incredible that he’s pulled that one off.”

Scholz has come from behind to become the improbable frontrunner, moving into the lead only last month after the long-suffering SPD had spent years hovering around 14%-15% in the polls.

“A lot of people laughed at us when Olaf Scholz was announced as our chancellor candidate,” said Sawsan Chebli, a leader in the SPD in Berlin and junior minister in the city government, in an interview. “The SPD had fallen to third place with about 14% in the polls and people were like ‘how can you even consider getting the chancellery at 14%?’. But Olaf has done a great job showing people he is the right person for the job. He is what a majority of people seems to like: calm, serious and thoughtful. Olaf isn’t ever going to be the most flamboyant person in the room. He tends to do things in an inconspicuous way but they get done well.”

Chebli said she senses renewed gratitude for the centre-left SPD following the ravages of the coronavirus crisis. “I also think that a lot of people have come to appreciate a strong SPD in the coalition with the CDU, and also the positions the SPD stands for and what the SPD can do to protect people in difficult times like now during the corona pandemic.“

There is in any event a palpable desire for change at the top in Germany, even if the SPD has been junior partners to Merkel’s CDU for the past eight years. Several conservative members of parliament have had to resign in the past year over financial corruption, a telling indication of a party that has held power for too long. Other conservatives have turned to gallows humor in recent weeks to try brace themselves for Sunday’s crushing defeat, especially if the proud party ends up with a record low of just above 20%, after winning more than 33% four years ago.

“It’s time for change in Germany and you can feel that desire just everywhere you go,” said Özcan Mutlu, a leader in the Green Party in Berlin and former member of parliament, in an interview with The Independent. “People want a new government – and they’re going to get their wish on Sunday.”

Here is a look at the most likely three-way scenarios in order of probability:

“Traffic light coalition” or Red-Green-Yellow

It’s called “traffic light” in Germany as a shorthand for the parties’ colours: SPD (red), Greens (green) and Free Democrats (yellow). The SPD, with its chancellor candidate Olaf Scholz, has said it would like to reenact the “Red-Green” coalition that ruled from 1998-2005. But together the parties are projected to win only 42% of the vote – thus needing a third partner. The least-objectional third partner would be the Free Democrats (FDP), who are polling 13%. But the pro-business, tax-cutting party that was long post-war West Germany’s kingmaker is playing hard-to-get. The smart money in Germany is thus betting on a “Traffic Light Coalition” even though there could be tensions between the left-leaning SPD-Green dominance on the one hand and the small centrist FDP on the other. Both the FDP and Greens have been out of the federal government for eight and 16 years, respectively, and both are eager to get back into power.

“Red-Red-Green” or “R2G”

This is a less likely three-way coalition made up of the SPD (25%), Greens (16.5%) and Linke party (6%) – mainly because the far-left Linke made up from the remnants of the former ruling party in Communist East Germany has called for disbanding Nato. That’s completely out of the question for legions of SPD and Greens voters who rely on the United States and Nato for their defence, and that stance has doomed any such similar R2G coalition at the national level in the past – even though such a tie-up would have been mathematically possible after the 2013 election. Scholz has cleverly opted against formally ruling out “R2G” for now despite dropping heavy hints it’s highly unlikely because of the Linke’s anti-Nato stance. Scholz has rejected that demand but declines to exclude the possibility of a three-way tie-up with the Linke in order to have some leverage with the FDP. That is why the conservatives are up in arms about the possibility of the Linke party, with its 6% of the vote, possibly getting seats in the next federal government as long as Scholz won’t rule it out. Even though the “Red Scare” tactics worked in the 1990s, Germans aren’t falling for it this time around.

“Deutschland” or “Mickey Mouse” coalition – or Red-Black-Yellow

This three-way coalition led by the SPD (25%), the CDU/CSU (23%) and FDP (11%) would be the preferred option for the conservatives and FDP but the centre-left SPD are done with the conservatives after being their junior partner for 12 of the past 16 years and seeing their own support crumble as a result from levels above 40% in the late 1990s to under 20% at times in recent years. It’s called the “German coalition” because its colours match those of the German flag (sort of, considering the national colours are actually black-red-gold and not black-red-yellow). Black-red-yellow nevertheless matches the clothes that Mickey Mouse wears.

Kenya coalition – SPD-CDU-Greens

This also possible but unlikely because the SPD (25%) is done with the CDU/CSU (23%) and it’s hard to imagine the CDU/CSU, which has ruled Germany for 52 of the past 72 years would settle for the junior partner role for the first time in post-war history. The Greens (16.5%) would also have little enthusiasm for a Kenya coalition, even though they won’t rule it out.

Jamaica coalition – CDU/CSU-Greens-FDP

This is also an unlikely alliance of “losers” because the Greens would rather partner with the SPD, which is expected to emerge triumphant on Sunday. Talks for a Jamaica coalition after the last election in 2017 dragged on for a month but collapsed when the FDP abandoned them. The SPD and Greens are also ideologically much closer than the CDU/CSU and Greens.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments