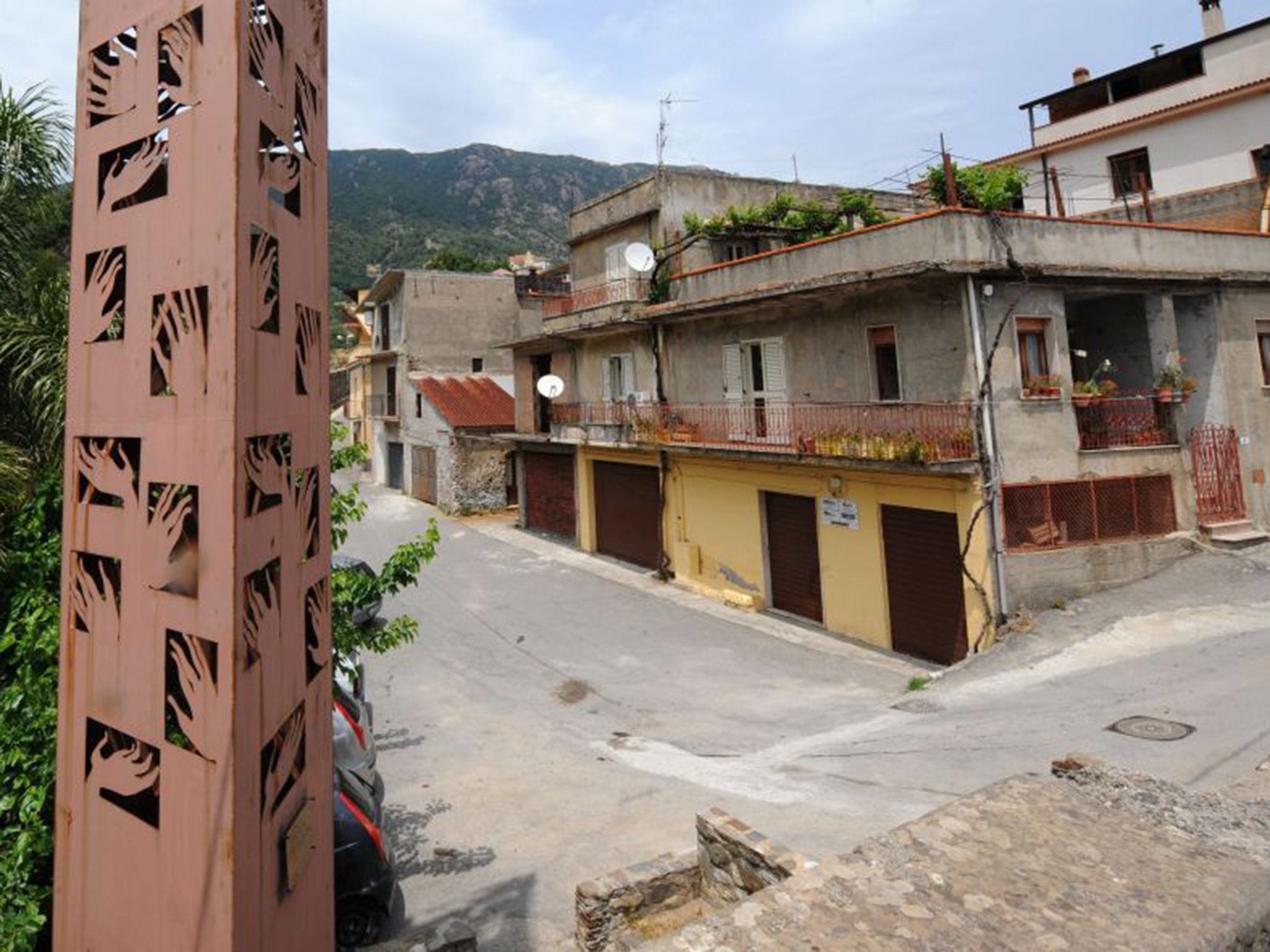

Fears for southern Italy as unemployment, organised crime and economic recession sees young people leave the country

With three-quarters of its youth unemployed, locals fear investment is pointless until organised crime is tackled

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The territory south of Rome, that includes many of Italy’s most enchanting places, in Sicily, Puglia and Campania, is fading away; choked by corruption, its economy mired in recession and its communities corroded by unemployment. The birth rate is at the lowest in history; you might say the beautiful south is dying.

Everyone agrees that southern Italy has a problem. But no one seems able to solve it – and time is running out.

Tourists flock there for the food, climate and scenery. But young locals, faced with 75 per cent youth unemployment, are buying one-way tickets to London and Berlin.

Later this month, Prime Minister Matteo Renzi will launch his Democratic Party’s “master plan” to resuscitate the south, often called Il Mezzogiorno. It can’t come a moment too soon.

Mr Renzi’s infrastructure minister and right-hand man Graziano Delrio has signalled that the government will boost investment in agriculture, manufacturing and tourism – the latter being the southern region’s most obvious strength.

Even some in Mr Renzi’s own party, though, are saying the measures will be too little, too late. Francesco Boccia, a Pugliese MP and economist, claimed that the Renzi government had in the past two years snatched €3.5bn (£2.57bn) earmarked for investment in the south in order to fund tax breaks for employers across Italy as part of plans to add flexibility to the labour market. “This was money that was meant for the south of Italy. It didn’t go there,” he said.

But, in a recent interview, Mr Delrio said: “What is lacking is not the money, but the efficiency with which the projects are executed, and in this respect there are delays and difficulties.” He said a new body, the Agency for National Cohesion, would help put that right.

Mr Boccia is not convinced by the ability of the agency to make a difference, given that the organisation itself is behind schedule. “It’s supposed to have been working since 2013 and so far it’s done nothing. So in a sense it’s already a flop,” he said.

Michele D’Ercole, the agency official with special responsibility for southern regions, said the organisation had been recruiting the right staff. He said it would soon be channelling investment where it was needed and checking progress in the south’s economy. “By measuring, for example, the amount of new rail track and tramlines, we can show if there have been improvements to transport,” he added.

Transport is an area that needs improvement, given that a rail journey of just 160 miles between the southern mainland’s two main cities –Bari and Naples – takes four hours or more and requires a change of trains.

Some observers, however, say no amount of investment is going to make a difference unless inroads are made against organised crime. “The number one problem is the absence of the state,” said Francesco Giavazzi, professor of economics at Bocconi University. “Calabria is particularly bad. It’s like a lost region.”

Economic stagnation and lack of opportunity has created a vicious circle in the most deprived areas. This week a priest in inner-city Naples, Father Alex Zanotelli, warned that social decay allowed young people to be easily recruited into a life of crime by mafia clans, whose corrupting influence was suffocating the economy. “In this situation, where are the young going to end up, apart from in the clutches of the Camorra?” he said.

On 11 September, Father Zanotelli spoke at the funeral of 17-year-old Gennaro Cesarano, whose death last weekend – linked to the latest outbreak of mob violence in the southern city – led him to conclude that the local situation was “worse, in some ways, than in the shanty towns of Nairobi”, where he had worked for several years.

Residents of Naples, Lecce in Puglia, and Catania, in Sicily, say the south has been forgotten. Marco, a 29-year-old in Lecce, who didn’t want to give his full name, has two degrees but is still waiting for an internship with a local company, funded by an European Union grant, that will pay him €400 a month. “It should have started at the beginning of the year. But I’m still waiting. That’s Italian bureaucracy.”

“I don’t want to leave the Salento [southern Puglia] or Italy. But I think I will follow some of my friends and go to London.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments