Fall of the Berlin Wall: Hear the stories of the last people who made it across from the East

In the summer of 1989, few suspected that East Germany was weeks away from collapse. So in Berlin, Hans-Peter Spitzner was about to risk his and his daughter's lives to flee across the Wall. And to the north Mario Wächtler was steeling himself for a 20-mile swim to freedom via the Baltic…

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At first there was incredulity. It soon gave way to wild jubilation and tears of unbridled, wholly unexpected joy. The fall of the Berlin Wall, 25 years ago next Sunday, changed our world: it ended the Cold War and it remains the most seismic political event in Europe since the Second World War.

It fell just a few minutes short of midnight on 9 November 1989. At the Bornholmer Strasse crossing point, East Germany's border guards faced a huge and increasingly angry 20,000-strong crowd of East Berliners chanting, "Open the gate." The guards feared for their lives.

After trying to contact his superior, but getting no response, the officer in charge finally succumbed and ordered that the barriers be flung open. " We're opening the floodgates now," he announced. A human tide of East Berliners poured into West Berlin.

Within the hour, all seven of the wall's crossing points had been thrown open and a giant party was in full swing on the streets of West Berlin. The collapse of Communism in Europe had begun.

The wall was both a monster and, at the same time, Communism's worst advertisement from the outset. It was a signal that East German socialism had failed. Before it was put up in the early hours of 13 August 1961, more than 3.5 million East Germans had voted with their feet and left for West Germany. That summer, East Germany did not even have enough farm labourers to bring in the harvest.

Many argue that the regime had to build the wall; its only other option would have been to admit to its own moral, political and economic bankruptcy and resign. That was something the Kremlin was anxious to prevent at all costs.

Western leaders grudgingly accepted it, too: 1961 was the height of the Cold War. The wall stabilised a precarious situation in Europe and kept at bay the prospect of a third world war.

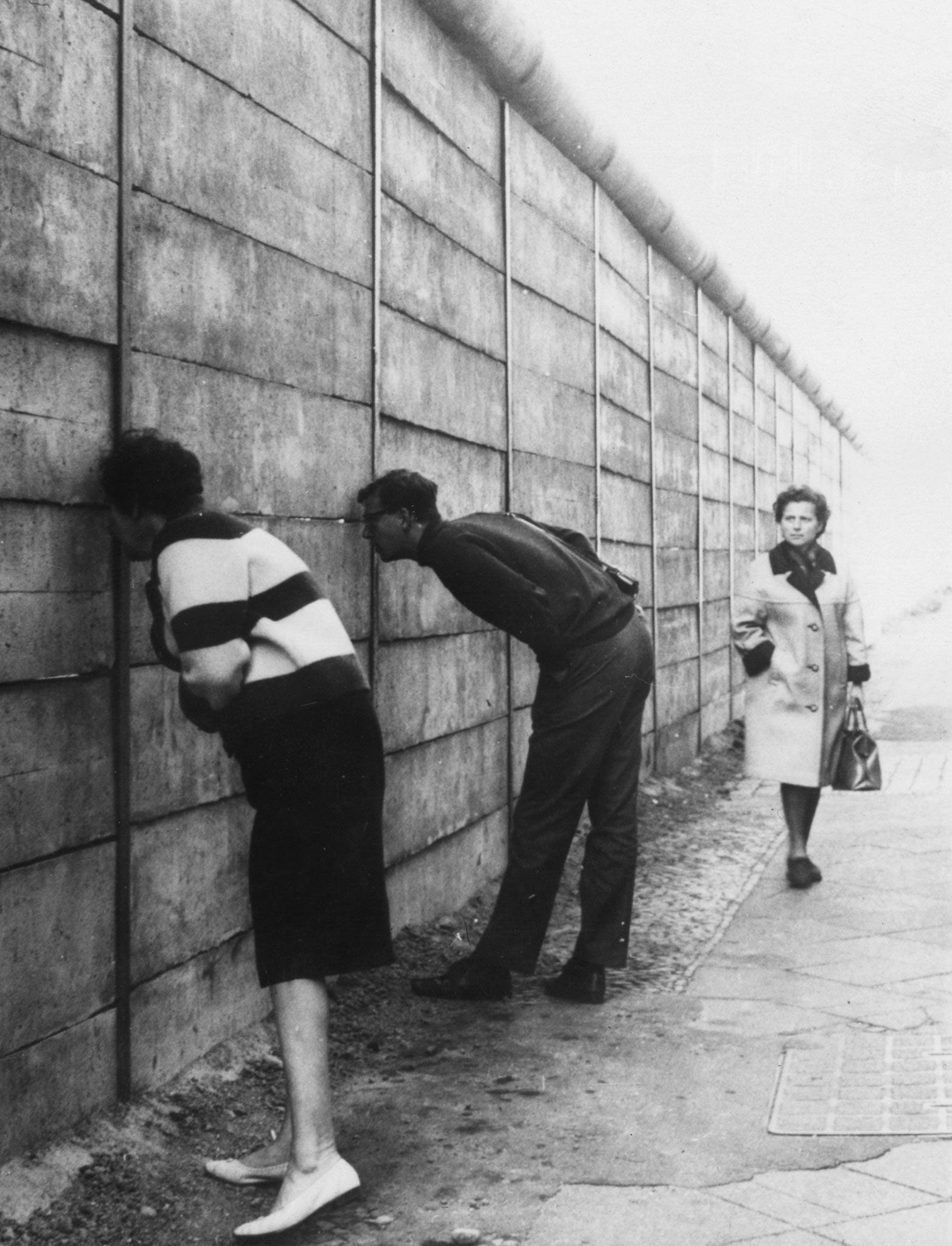

It began as barbed wire; then came breeze blocks and, subsequently, a 13ft-high concrete barrier topped with a round pipe to make scaling it difficult. It was manned round the clock by Kalashnikov-toting guards and equipped with watchtowers and searchlights. It encircled West Berlin, while its ugly sister – East Germany's heavily fortified Iron Curtain border – separated the Communist state from capitalist West Germany.

The wall bought Cold War stability at a ghastly human price. There is no final death count, but according to the most recent estimates, 718 people died either at the wall or at the inner German border, trying to escape to the West. Hundreds were shot dead; others suffered horrible injuries from shrapnel-spraying automatic firing devices that lined the border.

The last person to die at the wall was the 21-year-old East German Chris Gueffroy. He was shot through the heart by a border guard's bullet as he tried to escape to West Berlin on 5 February 1989 – only nine months before the wall disappeared into history.

The fall of the wall reunited Germans and their families, but it did so at a price. Many East Germans still see their country's subsequent reunification in 1990 both as a Western takeover and as an example of capitalism at its worst. Tens of thousands lost their jobs as Communist state collectives were disbanded.

Two million East Germans have emigrated to the West since reunification, the vast majority in search of jobs (a migration that came to a halt only last year, when the numbers returning equalled those leaving) – resulting in the demolition of tens of thousands of empty homes in the East. And economic data released this year shows that the East still has a lot of catching up to do. Its GDP still lags some 44 per cent behind that of the West, although a slow recovery is under way.

But among East Germans who experienced the Berlin Wall, there are very few who would want it back. Most cherish the democracy they have won and take pride in the fact that their current Chancellor is not only an Easterner like them but also one of Germany's most popular leaders ever. For a whole new generation, the wall is history.

Hans-Peter Spitzner – whose story as the last East German to flee across the wall can be read overleaf – maintains that today's reunited Germany is "the best Germany the Germans have ever had". Few would disagree.

Hans-Peter and Peggy Spitzner: The last people to cross the wall

It was a 4am ring on his doorbell, followed by a series of loud knocks, that made Hans-Peter Spitzner realise he had to flee East Germany.

Naked and half-asleep, he flipped open the latch to the two-roomed flat in Karl-Marx Stadt he shared with his wife, Ingrid, and their seven-year-old daughter, Peggy. The door was shoved open by four men in civilian clothes; one mumbled the words " house search". The visitors were members of the Stasi secret police.

Spitzner stood shaking in his bedroom as the officers ransacked his apartment. He was told to dress, bundled into the back of a Lada outside, and taken to Stasi HQ. "I was paralysed with fear and shock," Spitzner, now 60, recalls. "I had no idea what was going on or what I was supposed to have done."

He was ordered to put a piece of cloth into his pocket – he later learnt it was to enable sniffer dogs to recognise his smell. A piercingly bright lamp was pushed into his face. "After a minute or so, there was only the glare," he says. He was in the room for three hours. Strip-searched, photographed and finger-printed, he was told that from then on he was under surveillance. His crime? A teacher, Spitzner had crossed off all the names on his trade-union election ballot paper as they were all Communist party nominees.

"I knew I couldn't carry on living like this," he says. "Something had to change. The question was, what?" The answer, somewhat peculiarly, was provided by a Communist newspaper.

It described how soldiers from the Allied powers of Britain, France and the US who were stationed in West Berlin allegedly "sponged" off East Germany. Under post-war agreements, the Allies were allowed free access to the East. The paper claimed they changed their Western deutschmarks for Eastern money at favourable rates and stripped East Berlin's shops. The writer noted, in passing, that the Allied soldiers' cars were not checked by the Eastern authorities. "I thought, if the Allies could take home goods, they could take home people," Spitzner says.

Peter and his wife Ingrid began seriously thinking about escape in July 1989. Then Ingrid was suddenly given permission to travel to Austria for her aunt's 65th birthday. The East German politburo was flexible about married people with children travelling alone because it could make hostages of their families. Spitzner resolved to escape with his daughter, then meet Ingrid in the West. He told neither of his plan. He merely explained to Peggy that they were going to "meet Mummy".

On 16 August 1989, Spitzner and Peggy drove 120 miles to East Berlin. They spent the next two days hanging around the main Allied bus stop, begging the drivers to take them across to the West in the luggage compartment of their buses. "They all said it was too dangerous. By the end of the second day, I was just about to start for home when I spotted a black Toyota Camry with American licence plates in my wing mirror. A US soldier in uniform was in the driving seat."

The young serviceman, Eric Yaw, took seconds to consider the proposal, before saying: "OK, I'll do it." Peggy climbed into the boot with two holdalls and her father. The two lay jammed together. "I just remember it was dark and hot and we were going to see Mummy. I thought it was an adventure," Peggy, now 32, says.

After 20 minutes, the car pulled up at Checkpoint Charlie, the main crossing point for Allied soldiers through the Berlin Wall. Spitzner and Peggy heard the sound of guards' boots approaching. Spitzner was convinced they had been detected by heat scanners. If they were caught, they'd be arrested. If they fled, they'd be shot. "Then I heard the guard shout and the car started up. It was a black car and it was already so hot that the scanner couldn't spot us."

The Camry soon stopped, the boot flung open. Spitzner and Peggy blinked in the sunlight as Eric told them: "We're in the West, you can get out now." Spitzner was overjoyed, but he also had to tell Ingrid not to go back to East Germany. She wasn't in at the hotel where she was staying. "I dictated a frantic message to the hotel receptionist." Ingrid finally got it, and flew to West Berlin to join Spitzner and Peggy.

The family went back east after unification in 1990. They now live in a spacious modern house on the outskirts of what was Karl-Marx Stadt and is now Chemnitz. Peter still teaches. He became a city councillor and a member of Chancellor Angela Merkel's Christian Democratic Party. Sometimes he runs into the former Stasi officers who once made his life in the East a misery.

"They usually try and look through me," he says. " But I don't hate them for what they did any more." Despite the difficulties that many in the East have faced since reunification, Hans-Peter Spitzner remains adamant that, "Today's reunited Germany is the best Germany we've ever had."

Yet Peggy is not so sure. She now works as a call-centre supervisor and lives with her boyfriend in a small flat in Leipzig. "Capitalism may have won in Germany, but I'm not convinced it has all the answers – there must be something more than just profit out there," she says.

Eric Yaw was disciplined by the US Army for helping the Spitzners. He has long since left the US Army and now lives in a Mormon community near San Francisco. He visited Hans-Peter in Chemnitz earlier this year to celebrate his 60th birthday. "He always says that if he were faced with the same situation, he would do it again," says Spitzner.

Mario Wächtler: The last person to escape from East Germany

Fleeing the Iron Curtain was rarely a spectator sport. But despite the life-threatening risks involved, Mario Wächtler's escape from East Germany could almost be described as such: it ended with 1,500 people cheering him on as he dodged an armed border patrol, and a cash donation worth the equivalent of £3,000.

Wächtler was 24 when he became the last person to flee East Germany, on 2 September 1989, two months before the fall of the wall. It was a meticulously planned escape, carried out with the physical fitness and military precision one would expect of an SAS commando.

"I had wanted to get out of East Germany as a teenager," Wächtler, now 49, tells me from his home in the city of Winsen, near Hanover, where he has lived since his escape. "Border guards pulled me out of a train heading West when I was just 15. By the time I had reached my early twenties and completed my apprenticeship as a car mechanic, I realised that under Communism things were not going to change for the rest of my life. I had to get out."

A swimming-pool lifeguard in his home town of Karl-Marx Stadt, Wächtler resolved to "swim to freedom" across the 20 miles of Baltic then separating Communist East from capitalist West. He chose to start his escape from a wide sandy bay on the East German coast just west of the port Wismar. "The place was a holiday resort and across the water you could see West Germany and the ferries heading for Scandinavia. There were armed patrol boats and watchtowers equipped with searchlights to stop people fleeing, but I was convinced it must be possible to swim across to the West," Wächtler says.

He spent every weekend training for his escape on a four mile-long reservoir near his home, though he couldn't get hold of a neoprene swimsuit in Karl-Marx Stadt. "I had to travel to East Berlin to buy one, and even then the only one available in my size had short sleeves."

Wächtler covered the exposed parts of his body with a girlfriend's black tights, and wore a ski mask on his face. "I didn't dare wear goggles – the glass would have reflected if picked up by the border guards' searchlights. It would have been asking to get shot."

He spent the days before his flight attempt studying weather charts and making sure that the conditions were as near perfect as possible. On 2 September, his brother drove him up to the Baltic coast in his put-putting Trabant two-stroke-engined car.

The sea was almost flat calm. The water temperature was around 18C. As night fell, the lights of the West German beach resort of Timmendorfer Strand some 20 miles away began to sparkle in the distance. Wächtler slid into the water shortly after 11pm. His physical fitness was up to the mark and he felt good.

When he crossed a section of his route swept by the searchlights of border guards ashore, he reached for the snorkel he wore strapped to his waist and dived underwater. "I had calculated the distance correctly , but I didn't think it would take so long," he says.

As dawn broke, he was still swimming. Without the cover of darkness, he was now at risk of being spotted by one of the many East German patrol boats on the look-out for escapees. Wächtler's worst fears appeared confirmed around mid-morning. Still in the water, he saw a patrol boat approaching from 400 yards away. "My heart went into my mouth." He reached for his snorkel and dived. The patrol boat passed by; its crew had failed to spot him.

By late morning, Wächtler had reached the shipping lane that ran between East and West Germany. The captain of the Peter Pan, a West German ferry returning from Trelleborg in Sweden with 1,500 passengers aboard, just happened to spot him in the water. He stopped the engines and lowered a rescue boat – but the manoeuvre was spotted by the captain of an East German patrol boat nearby.

A frantic race for Wächtler began. The Peter Pan's rescue boat sped towards him, hotly pursued by the East German vessel. The Peter Pan's captain had informed his passengers and, by now, hundreds lined the ferry's bulwarks, clapping and cheering on the swimmer.

The Peter Pan's rescue boat got to Wächtler first. "I vividly remember the clapping as the boat was hauled back on board the ship. The passengers held a whip-round for me. I was given a drawer stuffed with about 6,000 West German marks."

Wächtler went to join his uncle in Hanover. He now runs a private ambulance service and has 40 employees. He lives with his wife and two grown-up children in the house he built for himself in Winsen. "The past 25 years have gone so fast," he says. "When I go back to what was East Germany, it hardly seems that the old Communist state ever existed. But I would never go back to live there."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments