Exclusive: The unseen photographs that throw new light on the First World War

A treasure trove of First World War photographs was discovered recently in France. Published here for the first time, they show British soldiers on their way to the Somme. But who took them? And who were these Tommies marching off to die?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The place, according to a jokingly chalked board, is "somewhere in France". The time is the winter of 1915 and the spring and summer of 1916. Hundreds of thousands of British and Empire soldiers, are preparing for The Big Push, the biggest British offensive of the 1914-18 war to date.

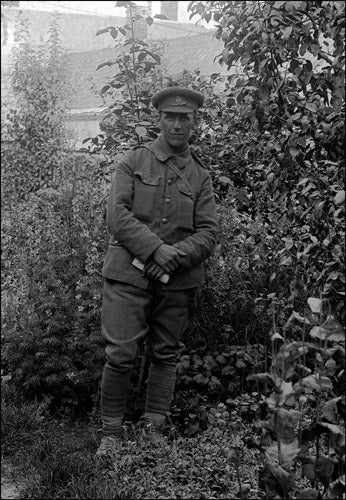

A local French photographer, almost certainly an amateur, possibly a farmer, has offered to take pictures for a few francs. Soldiers have queued to have a photograph taken to send back to their anxious but proud families in Britain or Australia or New Zealand.

Sometimes, the Tommies are snapped individually in front of the same battered door or in a pear and apple orchard. Sometimes they are photographed on horseback or in groups of comrades. A pretty six-year-old girl – the photographer's daughter? – occasionally stands with the soldiers or sits on their knees: a reminder of their families, of human tenderness and of a time when there was no war.

Many of the British soldiers are wearing rough sheepskins over their battle-dress: a tell-tale sign of the great overcoat shortage of the winter of 1915. The sheepskin-clad "Tommies" look, bizarrely, like ancient warriors or Greek or Yugoslav partisans.

Within a few months – or days, most probably – many of the soldiers were dead. The "somewhere in France" where these pictures were taken was a village called Warloy-Baillon in the département of the Somme. Ten miles to the east was the front line from which the British Army launched the most murderous battle of that, or any, war, which lasted from 1 July to late November 1916 and killed an estimated 1,000,000 British empire, French and German soldiers.

More than 90 years later, at least 400 glass photographic plates preserving the images were found in the loft of a barn at Warloy-Baillon and cast out as rubbish. In recent months, the plates, some in perfect condition, some badly damaged, have been lovingly assembled and their images printed, scanned and digitally restored by two Frenchmen.

Together, they form a poignant record of the British army on the eve of, or during, the battle of the Somme: the smiling, the scared, the scruffy, the smart, the formal, the jokey, the short, the tall, the young and the old. There is even an image of a 1914-18 war phenomenon which was rarely photographed and scarcely ever mentioned: a black Tommy in artillery uniform, with two white comrades.

The Independent Magazine publishes a large selection of the images here for the first time. More of the collection, including a few images of French civilians and soldiers, and possibly the photographer and his family, can be seen on The Independent website.

Who are these British and British Empire soldiers? Who was the photographer? Who was the little girl? From internal evidence in the pictures it is possible to identify the period and some of the military units – The Northumberland Fusiliers, the Tramways' Battalion of the Glasgow Highlanders, the Royal Leicestershire Regiment, the Royal Army Service Corps, the Royal Flying Corps, the Royal Engineers, a few Australians, a South African, a lone New Zealander.

The identity of the soldiers is, and may always remain, a mystery. They are, in a sense, a photographic parallel to the 400 unknown British and Australian soldiers now being excavated from eight mass graves near Fromelles, 50 miles to the north. Including the figures in the group photos, well over 400 unknown Tommy faces come back to us through the mists of time and battle.

Most First World War photographs show smart soldiers before leaving home for the front or exhausted soldiers during or just after combat. Here we see the clear and often modern-looking features of soldiers at rest, either before – or in some cases, it seems – just after fighting in the trenches to the east.

Many of the images show medical orderlies. Warloy-Baillon was the site of a large hospital, taken over by the British Army. Other soldiers were evidently photographed while in reserve, or engaged in behind-the-line tasks, or after recovering from minor wounds.

There are several gems. Who is the "black Tommy"? There was already a small black community in Britain in 1914 – in Cardiff, in Liverpool and in the North East. Black men are known to have volunteered and fought in the trenches, but very few photographs of them exist.

Who, also, is the giant of a British soldier, possibly as much as seven feet tall, sitting in front of two standard-sized comrades? Who was the Tommy who asked the photographer to take a picture of his back, which has been elaborately tattooed with the faces of the British royal family? Why is one group of soldiers holding a large rag doll?

Click here to help us answer these questions and more.

The survival of the images is owed to two local men: Bernard Gardin, aged 60, a photography enthusiast; and Dominique Zanardi, 49, proprietor of the "Tommy" café at Pozières, a village in the heart of the Somme battlefields.

M. Gardin was given a batch of about 270 glass plates by someone who knew of his hobby. He approached M. Zanardi, who has a collection of Great War memorabilia, including a football dug up 12 years ago inside a British soldier's rucksack. M. Zanardi, it turned out, already had 130 similar plates which he had gathered from other local people.

"About three years ago, someone bought a barn near Warloy-Baillon," M. Zanardi said. "They found the glass plates in the loft and just threw them out as rubbish. Many of them were picked up and taken away by passers-by. I started collecting them and had reached over 100 when M. Gardin turned up with this great batch of 270. They must also, originally, have come from the same source. There may be many more out there which we have not yet been found."

M. Gardin and M. Zanardi have had prints made, at their own expense, from the original plates. M. Gardin describes these as "9 x 12 centimetre glass plates, of the kind used at the time by amateur photographers. A professional would have used a camera with bigger plates, 18 centimetres x 24."

Amateur or not, the quality of many of the images turned out to be excellent. Some plates, however, had been damaged. M. Gardin scanned the prints into a computer and set about digitally restoring the images. "If it's just a question of filling in a wall or part of a uniform, it's quite easy," he said. "Faces, and especially eyes, are very tricky."

Prints of more than 100 of the unknown soldiers have now been framed and exhibited in M. Zanardi's café in Pozières. Others will join them when they are ready.

M. Zanardi's attempts to identify the photographer and the images of French civilians, and a handful of French soldiers, have got nowhere. "My belief is that he lived close to the barn where the plates were found," he said. "He may have been a farmer. The plates were just stacked up after he printed photographs from them and then forgotten for more than 90 years."

M. Gardin told me: "We think that they form an important, and moving, historical record. Our motive in restoring them was not financial. It was a tribute to all the British soldiers who fought here and also to an unknown photographer."

Identical copies of these images must have been sent home to mothers and wives and sweethearts in late 1915 and the first half of 1916. Will someone out there recognise their Great Grandad or their Great Uncle Bill?

Although some research has been conducted into the photographs, much hard work is yet to be done. Such compelling images must have a story attached; and with your help we hope to uncover as much of their fascinating history as possible. Click here to see how you can help.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments