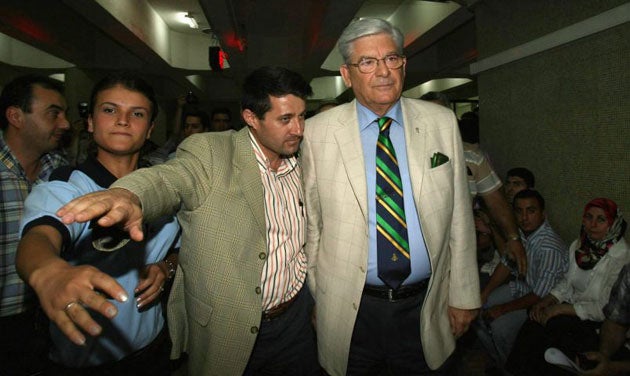

Democracy on trial in Turkey as 86 face coup attempt charge

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Turkey's most important political trial in more than a decade starts near Istanbul today, amid hopes the country may finally be able to crush shadowy criminal groups that, for decades, have hobbled its democratic development.

The 86 defendants, prominent secularists and right-wingers united only by their authoritarian ultra-nationalism, stand accused of attempting to remove the government of Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan by force. The indictment against them, a 2,455-page door-stopper, reads like a Dan Brown novel.

Beginning with the discovery of 27 hand-grenades in the Istanbul home of a retired military officer last June, the prosecutors accumulated evidence linking the gang to assassinations stretching back more than 15 years.

The gang's aim, they assert, was to use high-profile murders to stir up social tensions, easing the way for military intervention against a ruling party which has its roots in political Islam.

The accused – among them senior retired military officers, mafiosi and prominent academics and journalists – are alleged to have commissioned the murder of a High Court judge in April 2006. Originally blamed on Islamists, the killing triggered a secularist backlash against the government that culminated in a veiled coup threat last year and a court attempt to close the ruling AK Party this February.

The government narrowly escaped closure in July, but divisions over Islam remain deep. Debates about the gang the Turkish media has called Ergenekon reflect the polarisations.

For much of the pro-government media, Ergenekon is behind every act of terrorism in the past half-century. Many secularists dismiss the trial as a government-backed plot to neutralise its enemies. Who has heard of a coup attempt started with 27 grenades, they ask contemptuously.

Belma Akcura, an investigative journalist who has been following the Ergenekon investigations closely, is no fan of the Justice and Development (AKP) government. But she is critical of the secularist view. "Think of it like this", she says. "The affair of the 27 grenades is like a kid caught stealing sweets from a shop. Questioned by the police, he turns out to be part of a group stealing sweets from every single shop in the whole of Turkey."

In the past, it was the left-leaning secularists who were the ones who worked hardest to shed light on what Turks called the "Deep State", paramilitary groups with links to the military, police and politicians – and possibly the CIA – that are believed to have been active in Turkey since the 1950s.

The reason for their change of heart, Ms Akcura says, stems from radical changes in threat perceptions in Turkey. In the 1970s, extreme right-wing nationalists were almost certainly used by certain state activists to stoke a near-civil war against left-wingers that culminated in a military coup in 1980. The same men reappeared at the height of a Kurdish uprising in the 1990s, forming death squads that assassinated hundreds of Kurdish activists. None of the murders has been solved.

Several of the men on trial today are believed to have played a key role a decade ago. One of the defendants, retired general Veli Kucuk, was the military police commander in a western Turkish province notorious as a killing ground for pro-Kurdish businessmen. Another retired military police chief who fled to Russia months ago to avoid arrest, headed a command post where two Kurdish politicians were taken in for questioning in 2001. The two men have not been seen since. Yet Belma Akcura thinks pro-government media claims that Ergenekon is the latest face of the Deep State slightly miss the point. "In the past, these people were part of the state," she says. "Now they are outside, trying to get in."

The heyday of paramilitary groups in Turkey came to an unexpected end in November 1996, after a Mercedes with an Istanbul police chief, a pro-government Kurdish chieftain and a notorious right-wing killer crashed at high speed. Local police found machine-guns, grenades and diplomatic passports signed by the then interior minister in the boot of the car, sparking a media frenzy.

Subsequent investigations into the so-called Susurluk affair showed how mafiosi on the state payroll had been involved in criminal activities. Yet, while dozens were jailed, the gang heads remained free. The last man to talk to the right-wing killer before he died in the crash, General Kucuk, refused to give evidence to a parliamentary commission and was promptly promoted by the army. Many analysts see the fact that General Kucuk is now in the dock as evidence of a fundamental change in the balance of power in Turkey.

"What we are living through today are the birth pains of a new regime – the death of 60 years of controlled democracy, the birth of a Turkey that has the full democracy it deserves", says Alper Gormus, the left-leaning editor of a magazine that was closed last year after it revealed evidence of military coup plans in 2004.

For others, the real test of Turkey's transformation lies in the fate of two four-star generals who were detained this July in connection with the coup plot. The two men, the highest-ranking officers ever arrested in Turkey, have yet to be charged in connection with Ergenekon.

"The mentality that a privileged few can act against the interests of the people is like a cancer eating away at the flesh of this country," says Mehmet Metiner, a former adviser to the Prime Mminister. "Unless this case is taken to its logical conclusion, Turkish democracy will continue to limp."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments