Croatia election: Swastika on pitch during Euro 2016 qualifier with Italy is symbolic of the rise of the far right in the Balkan state

Serbs and other minorities live in fear as ultra-nationalists uses fascist chants and emblems ahead of poll, fuelled by deep economic hardship

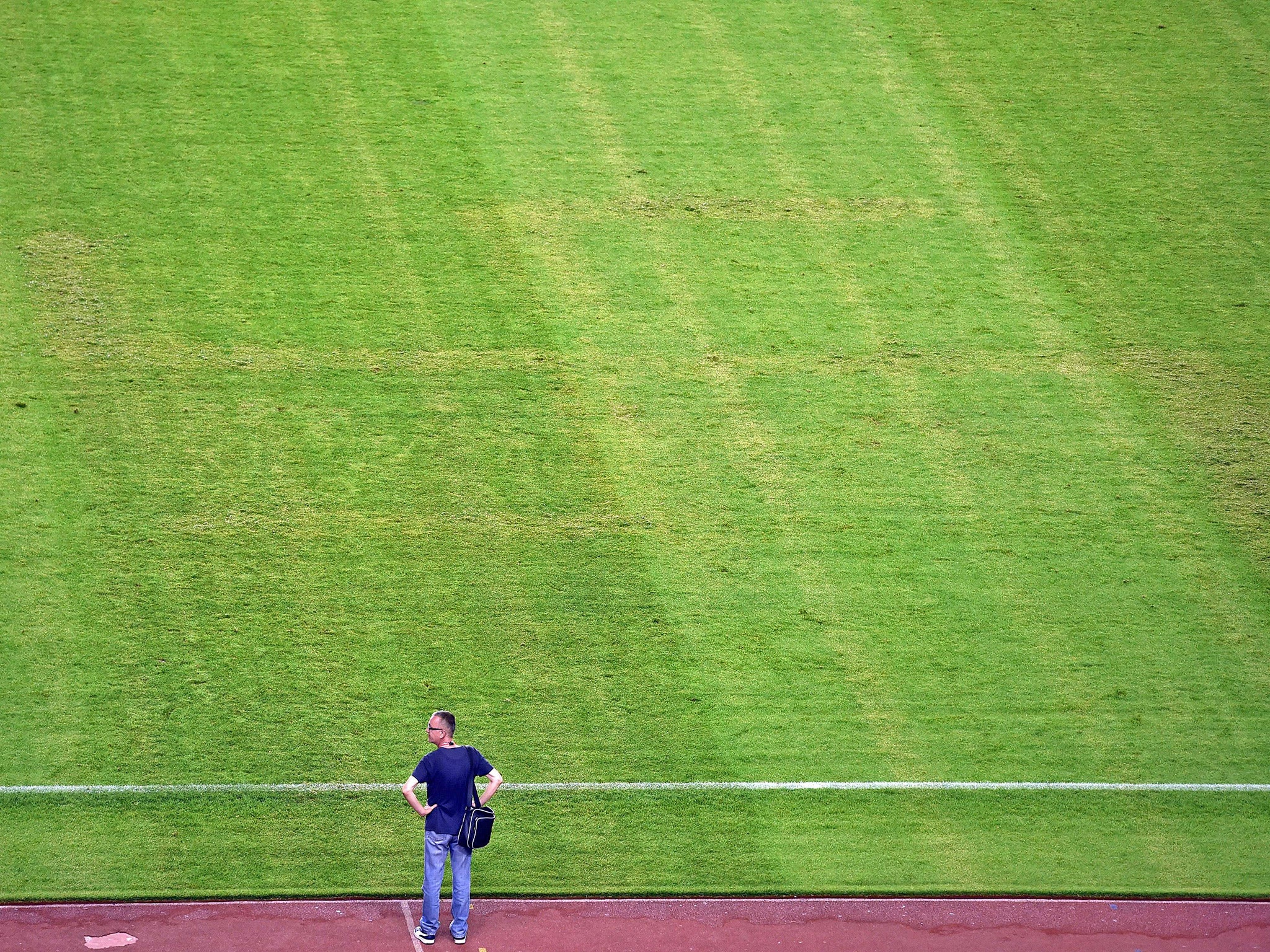

It was one of the biggest nights in Croatia’s sporting calendar: a European Championship qualifying match with Italy. In a game televised around the world, a gigantic swastika materialised on the pitch under the shocked gaze of European football officials.

The swastika, sprayed by an unknown vandal with a chemical that became visible only when floodlights came on, has become the most potent symbol of a rise in ultra-nationalist sentiment that appears to be bleeding into the mainstream population in the EU’s newest member state.

But it’s not the only one. In the ethnically mixed towns of eastern Croatia, road signs in the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet have been destroyed and Serbian Orthodox churches have been vandalised with a “U” symbol representing the Nazi-linked II Ustasha regime. Ustasha chants are heard at sports stadiums and rock concerts. During the Second World War, the country sent tens of thousands of Serbs, Jews and Gypsies to Nazi death camps. But the Balkan state has called for change after the global outcry prompted by the swastika on the field. “This act has inflicted immeasurable damage on the reputation of Croatian citizens and their homeland all over the world,” said Croatia’s new conservative President, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic. “Therefore, we must finally put a stop to such things.”

The rise of the right in Croatia has been fuelled by deep economic hardship and growing public anger over the inability of the left-leaning government to deal with it, even after the country entered the EU two years ago. Dreams of sudden riches have not materialised.

Minorities, especially Serbs, have feared for their safety since Ms Grabar-Kitarovic was elected in December. The anti-Serb graffiti has evoked memories of the bloodshed that engulfed the region during the 1990s Balkan wars that tore the former Yugoslavia apart.

At an event last month in southern Austria, Croatian ultra-nationalist Ivica Safaric proudly brandished the “U” Ustasha symbol on a medallion around his neck. His companions in black shirts raised their right arms in a Nazi salute, shouting the battle call “For the homeland – Ready!” which was used by wartime Croatian fascist troops.

“I respect the Ustasha movement because it created the independent state of Croatia,” said Mr Safaric, who fought for Croatia’s independence in the 1990s.

The gathering in Bleiburg was a memorial to tens of thousands of pro-Nazi soldiers, their families, children and civilians killed by communist guerrillas at the end of the war in 1945.

A major commemoration for the Bleiburg massacre victims is held annually in May, but last month’s gathering was by far the largest, with an estimated 40,000 people participating. It happened as much of Europe marked the 70th anniversary of liberation from the Nazis, and the pro-Nazi imagery at Bleiburg was met by a muted response from Croatia’s politicians.

Ms Grabar-Kitarovic endorsed the Bleiburg commemorations and honoured the victims days ahead of the main event, but did not attend. She also paid an informal visit to the site of an Ustasha-run death camp in Jasenovac, but also did not attend official commemorations of the 70th anniversary of the camp’s liberation. In an illustration of the ideological divide, Croatia’s embattled leftist Prime Minister Zoran Milanovic did participate in the official ceremonies at Jasenovac, where at least 80,000 people, mostly Serbs, were killed. He urged Croats to acknowledge what happened in the death camp as being part of Nazi genocide.

Analysts say the right-wing advance in Croatia – a country deeply split between left-wing and conservative traditions – has surged to its highest point since it gained independence from the Serb-led Yugoslavia in the 1991-95 war.

Minority Serbs, who fought against Croatia’s independence during the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s, have been under increasing pressure from the nationalists. Croatian war veterans campaigning under the slogan “100 per cent Croatia” – implying an ethnically pure state – have demanded that Serbs stop using the Cyrillic alphabet in Croatia, although their right to do so is guaranteed by the country’s laws.

Most Croatian officials are downplaying the far-right surge, saying it is part of pre-election campaigning.

“Croatian society is not better or worse than in the other EU countries,” said parliament’s Speaker Josip Leko. “We are in an election year and some themes are being opened by those who want to attract sympathisers.”

AP

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks