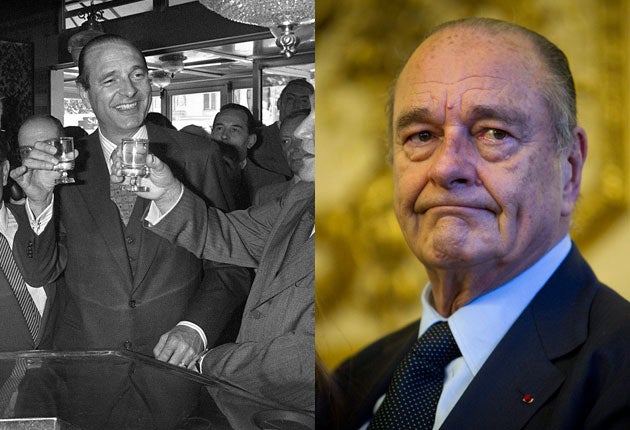

Chirac faces corruption trial that threatens to leave his legacy in tatters

France's ex-President is finally due in court, accused of embezzling €2m to further his career. So why is he still such a popular figure?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a small village lost in the wooded hills of South-west France, there is a building that looks like a cross between a battery chicken farm and a provincial airport terminal.

The building complex contains 15,000 objects of epic eclecticism. They include: a 5ft-long, stuffed, prehistoric fish; a pair of unworn blue cowboy-boots; a porcelain model of a sumo wrestler standing on one foot; a plastic cow; a New York Fire Department helmet; a chess set in which all four bishops are Desmond Tutu ; and a Winston Churchill pen and cigar set (presented by the grateful people of Britain).

The building houses the Musée du Président Jacques Chirac, a tribute to his 12 years as president of France (1995 to 2007) and the permanent resting place for the tons of ceremonial bric-a-brac that he received while in office.

This institution – one of the weirdest and least commercially successful museums in the world – is a perfect monument to the Chirac era. It has some wonderful moments. It is full of incronguous odds and ends. It attempts a bit of everything and it finally takes you nowhere very much.

The museum may also be emblematic of Mr Chirac's career in another way. It relies heavily on subsidies from the taxpayer. The €16m (£13.7m) that it cost to build the museum came from French national and regional governments and from the European Union's regional development fund. For each €4 that a visitor pays to enter the museum, the Corrèze departément council has to pay out another €30 to keep it afloat.

Over the next three weeks, a court in Paris is due to hear evidence that the whole of Mr Chirac's career was subsidised – illegally – by the taxpayers, not of Corrèze (his provincial fiefdom) but of Paris (his political power base). There is a possibility that the trial will be postponed. A last-minute constitutional objection may have to be referred to higher authority.

Only two previous former French heads of state have been placed on trial, Louis XVI in 1792 and Field Marshall Phillippe Pétain in 1945.

Beside the charges faced by his predecessors – "treachery against the people" and "treason" – the accusations against Mr Chirac may appear trivial. He is accused of embezzling, while mayor of Paris between 1977 and 1995, about €2m in Parisian taxpayers' money to fund his political party and to give sweeteners to his friends and public figures, including Charles de Gaulle's grandson.

This will be a trial with no prosecution and, in a sense, no victim. The public prosecution service concluded last year that Mr Chirac had no case to answer. The main victim, the city of Paris, has withdrawn its complaint after being reimbursed by Mr Chirac's friends and Nicolas Sarkozy's centre-right party.

Even if convicted (which is far from certain), Mr Chirac will probably get no more than a fine and a suspended sentence. At 78, he is, his friends and wife point out, an infirm old man who does not always recognise his friends and is given to uncharacteristic bursts of bad temper. They ask why he is being tried at all.

The former president is on trial because two sets of independent examining magistrates, who had painstakingly investigated two separate sets of corruption allegations against him, overruled the state prosecutor. They insisted the public interest demanded a trial because the accusations against Mr Chirac pointed to a prolonged and shameless conspiracy to pillage public funds over nearly two decades. As mayor of Paris, they argued, he created and ran a complex system of "embezzlement" to "increase his influence" and finance his rise to power.

The main case against Mr Chirac at the month-long trial will be made by two anti-corruption pressure groups which have declared themselves to be civil plaintiffs. They will argue that the relatively minor allegations against the former president are serious enough, but just the tip of the iceberg. Mr Chirac's now-defunct, centre-right party, the Rassemblement pour la République (RPR), was, they say, funded for years by a series of interlocking scams. These allegedly included kickbacks on Paris town hall contracts. They also included the placing of party officials on the town hall payroll and the appointment of generously paid special advisers to the mayor of Paris, most of whom had no connection with the French capital.

There is undisputed evidence that 21 people who were paid by the town hall actually worked for the RPR, which has been merged into Mr Sarkozy's Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP). There were probably far more. What is in dispute is whether Mr Chirac – then mayor of Paris and leader of the RPR – knew what was going on.

Amongst the phantom "special advisers" was a man who worked in Mr Chirac's constituency office, 300 miles from the capital and a few miles from Mr Chirac's château, near the village of Sarran, in Corréze. Sarran is now dominated by the Chirac museum.

In one respect, the museum is not emblematic of Mr Chirac's life and career. Since he was succeeded by his estranged former protégé, Mr Sarkozy, in 2007, visits to the Chirac museum have slumped. When The Independent called in last week, there were only four other members of the public on two floors of exhibitions. In the two large car parks there were three cars and a camper van. Attendance reached over 60,000 in the first full year in 2002; it fell to less than 30,000 in 2009.

Despite this month's trial, Mr Chirac has never been so popular. Recent polls have made him the most-liked political figure in France, with over 70 per cent approval ratings – much higher than anything that he achieved while in office.

When Mr Chirac attended the annual agricultural show in Paris last month – a rare public outing for him these days – he was mobbed by admirers for 20 minutes.

Mr Chirac's popularity is partly a mirror image of Mr Sarkozy's unpopularity. Mr Sarkozy came to power promising to be a kind of "anti-Chirac": more purposeful, more hands-on, more consistent, less hostile to American influence. After nearly four years of Mr Sarkozy's vainglorious and frenetic leadership, many French people – including, bizarrely, many on the left – now look back at Mr Chirac as a rascally, wise and reassuring uncle who did not achieve much but at least had the good sense to oppose the Iraq war in 2003.

Among the other visitors to the museum was a local woman, Josette, 53, and her 10-year-old grandson. "We've looked around before and there's not much worth seeing," she said. "But then again, there's nothing else to do here in the school holidays."

Asked about today's trial, she said: "That is all just politics. All politicians in France find ways of taking money to fund what they do... Chirac was no different but he was, at least, more human than some of the others.

"[François] Mitterrand was a cold man. Sarkozy is a cold man. I think people look back now and they think of Chirac as a kindly man."

But there was also, his critics and accusers argue, another Mr Chirac: a cynical, calculating and, when occasion demanded, brutal politician. This was the man who: back-stabbed his way to leadership of the Gaullist movement in the 1970s; betrayed President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing in 1981; was, successively, a virulent Euro-sceptic and then a flag-waving European; and artfully dispatched all centre-right rivals, until Mr Sarkozy came along. Over the next four weeks, with no help from the state prosecutor, the trial judge, Dominique Pauthe, must decide whether Mr Chirac was also a spider at the centre of a complex web of embezzlement of public funds.

The first day of the trial today will be given over to procedural arguments. Convoluted objections on constitutional principle have been put forward by the lawyer for a minor defendant, almost certainly with the connivance of the Chirac clan.

The ex-president will not attend. If the trial goes ahead, Mr Chirac will be present from tomorrow until 3 April, in the same courtroom in the Palais de Justice in Paris, which also witnessed the trial of Queen Marie Antoinette in 1793.

Mr Chirac does not risk the guillotine. All the same, his wife has told friends that she is worried.

Bernadette Chirac, who is still a local councillor in Correze, was a main mover in the creation of the Chirac museum in Sarran as a monument to his elusive legacy. She is said to be fearful that – whether her husband is convicted or not – his legacy will be forever tainted by the odour of corruption.

Leaders on Trial

Jacques Chirac

The president for 12 years from 1995 is accused of embezzling taxpayers' money while mayor of Paris to fund his political party.

Louis XVI

Tried and sent to the guillotine in 1793 following the French Revolution. Among the charges made against Louis XVI, were attacking the "sovereignty of the people" and "working to overthrow" the constitution.

Field Marshal Philippe Pétain

Convicted of treason and sentenced to death in 1945, later commuted to solitary confinement for life. A war hero in the First World War, Pétain, was appointed vice-premier during Hitler's invasion of France. He later sued for peace, and became "Chief of State" for the collaborationist Vichy regime in the south. Following his post-war conviction for treason, he died in prison.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments