‘I was alive but almost already dead’: Former Charlie Hebdo culture writer’s journey through survival

Five years on from the Paris terror attack, writes Michael Cavna, art and tragedy intertwine in Philippe Lancon’s award-winning book

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Philippe Lancon is billed on his memoir as the survivor of a massacre, but he will tell you that is not entirely true. Because the Philippe Lancon who was soon to be shot one morning in Paris was a different man on a different path, and try as he might, the author says, “I can’t go back.”

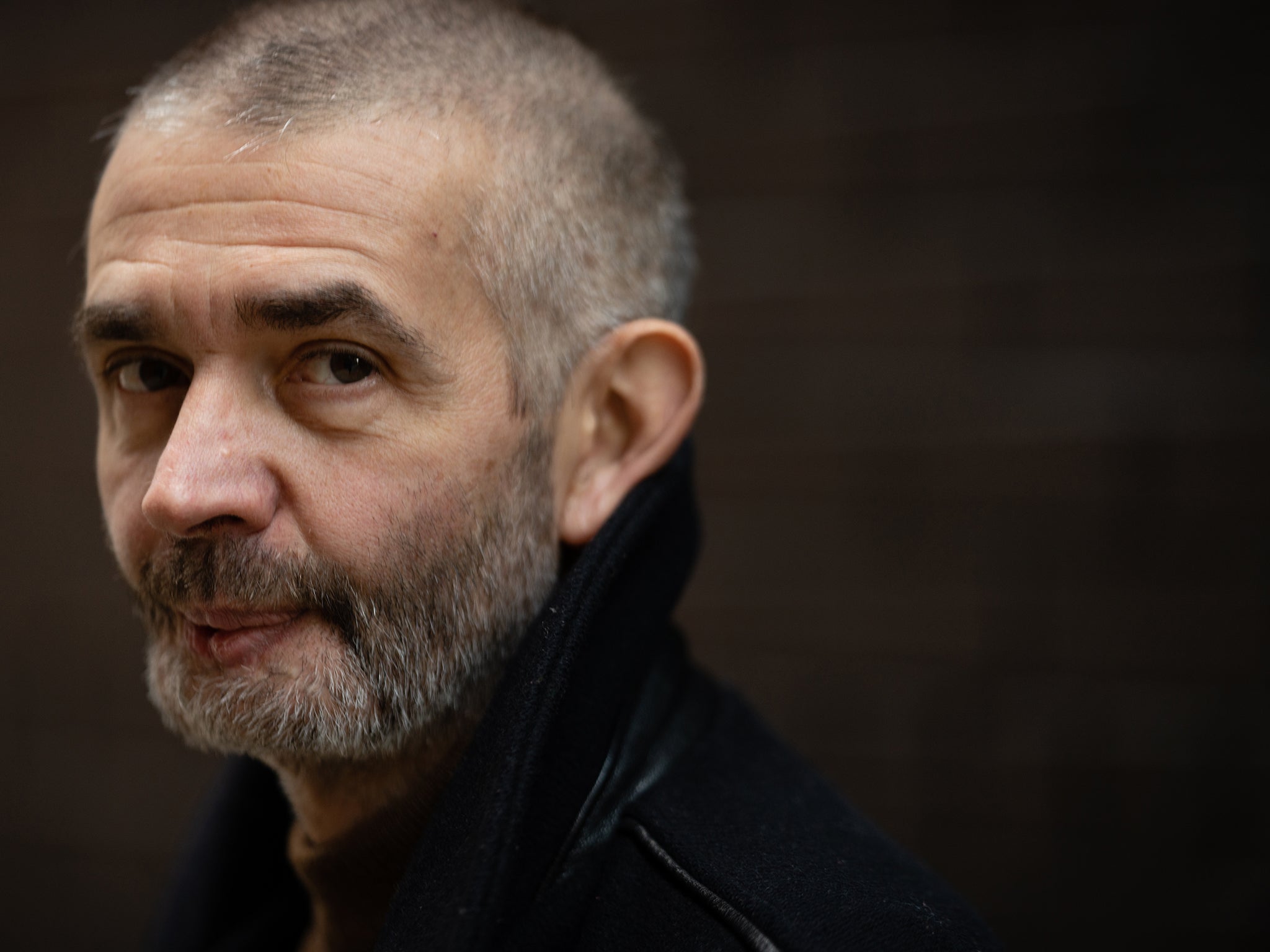

Five years ago this month, Lancon physically survived a workplace attack that left him lying amid the blood and blown-out body parts of friends. And when he speaks now, while sitting in a K Street hotel lobby on a grey Washington day, his lasting wounds are evident in his poignant words spoken through surgically repaired lips.

Lancon was a contributor to the Paris newspaper Liberation and magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015 when two terrorist gunmen entered Hebdo’s editorial offices and killed 12 people, including several well-known artists, after the satirical weekly published controversial cartoons depicting Muhammad. Eleven people were wounded including Lancon, a culture critic who was shot in the face and arm.

Lancon played dead on the floor, opening his eyes only to glimpse the legs of the gunman who had just been hovering over him.

Lancon says the attack, unfolding over a couple of minutes, overwhelmed his senses. “Everything was simultaneously foggy, precise and detached,” he writes in his award-winning book Disturbance: Surviving Charlie Hebdo, newly translated for the English-speaking market. The French title is Le Lambeau, which refers to a “fragment,” and the book tells of shattered teeth and shredded flesh, as well as fragments of time and memory and a tattered life.

One minute that Wednesday morning, Lancon was in an upbeat staff meeting, as cartoonist Georges Wolinski drew bawdy sketches, the artist known as Cabu marvelled at a Sixties photograph of jazz drummer Elvin Jones, and writer Bernard Maris and editor-cartoonist Stephane “Charb” Charbonnier teased Lancon about his next assignment. The next minute, Lancon heard sharp firecracker-like sounds from the hallway – “not at all [like] the noisy detonations in movies”, he writes.

All four of those colleagues would die in the attack. Immediately afterwards, Lancon, 56, felt that “I was alive but almost already dead”, he recounts in Disturbance, adding: “What remained of me?”

Five years later, Lancon is describing how it took many people to bring him back from almost already dead. Lean and alert, his hair and beard close-cropped, he looks directly at you with dark placid eyes. A short time later, while heading to a bookstore appearance, he dons a navy-blue pea coat like the pierced one he was wearing during the massacre.

The most visible trace of the attack is the lower right side of Lancon’s face; his beard partially covers where his jaw had to be rebuilt with a leg bone. The shooting left a quarter of his face like “a crater of torn, hanging flesh”, as if applied as a gouache blob “by the hand of a childish painter”, he writes, adding that the wound “had turned me into a monster”.

Less immediately apparent is how the attack has affected Lancon’s mind. As he speaks, his words do not convey intense feelings, be it rage or sorrow. He attributes such emotional equanimity partly to being a reporter trained in detachment since his days decades ago dropping into hot spots like Iraq. Yet it also reflects his sense of acceptance.

“Before, I used to be more angry,” Lancon says, “but now it’s very difficult for me to get angry. You have to let it go.” He even harbours no fury towards the two gunmen, saying their actions were symptomatic of larger social sicknesses.

When Lancon describes his traumatic experience, he, ever the culture critic, often relies upon the lens of art. Some aspects of the attack were like a Quentin Tarantino movie. And the aftermath was like a darker version of the painting La Danse, with the author writing that “the dead were almost holding hands”, like Matisse’s famous circle of interlocked figures. He references Shakespeare and Proust, and while in Washington, a stroll down a city alley reminds him of a scene in Three Days of the Condor, the spy thriller in which Robert Redford’s character escapes an office massacre.

But perhaps most tellingly, Lancon turns to an American western when trying to describe how the massacre irrevocably cleaved his life in two.

“It’s like The Outlaw Josey Wales,” says Lancon of the 1976 movie in which Clint Eastwood’s civil war-era character on the run must cross a river by tethered barge and then cut off all possibility of return. “I could see on the other side my former life,” he says. “I think it is not good to mourn that you can’t go back to the other bank. Josey Wales has to forget the revenge and die a bit.”

As he endured more than 20 surgeries, he watched just how many people helped reconstruct a life. Beyond the attack, Disturbance – largely written from Rome in 2017 – is a keenly observed journey of recovery as Lancon chronicles the cast of characters in his hospital, from loved ones to caregivers to his bodyguard to patients worse off than he. “I wrote this as a writer, not a patient,” he says. “This was not therapy.”

Speaking about the critically acclaimed book also allows him to reflect on Charlie Hebdo’s form of dark and provocative satire. “Some of the cartoons are good, some are not good. These cartoons are not democratic – they are not meant for everyone,” says Lancon, noting that prior to the shooting, even his parents did not read Charlie Hebdo. Later, at the bookstore appearance, he says he does embrace “the freedom for the cartoonists to do what they want to do. And then it’s very simple: If these are bad cartoons,” then Charlie Hebdo “won’t have readers, and the magazine dies naturally”.

Mostly, though, when he thinks about Charlie Hebdo, the sense of personal tragedy is still strong. Imagine you returned to where you work, he says, and half your colleagues are gone like ghosts.

And still, art and tragedy are intertwined. He once returned to the scrubbed former Hebdo offices and asked authorities to return his lost jazz book – the cherished one that Cabu looked at moments before he died. Bloodstains had melted into the book’s black and white photos. “My blood,” he writes, “perhaps mixed with that of my neighbours – had stuck [pages] together as it dried.”

And when Lancon sits on the edge of his hotel chair, as if leaning into life, he talks about men who return from the wreckage in Robinson Crusoe and the Tom Hanks-starring Cast Away. Lancon is a survivor sparked by curiosity. “Life is strong and until you are dead, it brings you surprise,” he says.

“I am neither too optimistic or pessimistic. Now I take life as it comes.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments