‘Who lives to remember?’: Trauma of two boys shot dead crossing the Berlin Wall lingers on

Berlin Wall Anniversary: Death of boys was swept under the carpet by East German authorities, but as celebrations mark 30 years since the wall fell, their killings are a reminder of the ‘razor blade’ human effects of the barricade, finds Borzou Daragahi

It was just after dark when the two boys tried to make a run for it over the wall. Jorg Hartmann was slight and thin, a 10-year-old with longish blond hair that made many mistake him for a girl. The other boy, 13-year-old Lothar Schleusener, was the son of an electrician and a seamstress. Both lived in the working class Friedrichshain district of Berlin.

No one knows exactly what prompted the two neighbours to make the risky and dangerous dash across the frontier in the Treptow district that evening in 1966. The day before, Jorg had asked his grandmother for the address of his father, who lived on the other side of the increasingly formidable barrier of concrete and barbed wire that had been dividing the city, in West Berlin. Lothar also had enquired about family living on the other side.

According to court testimony three decades later, a border guard on the Eastern side said he “opened fire because he did not know what else to do and felt this was his duty”. He unleashed 40 rounds, before climbing down and finding that he had shot at children, claiming he was “totally shattered” by the realisation.

Jorg died immediately, while Lothar was taken to a police hospital where he succumbed to his gunshot wounds later that day, after an interrogation.

West Berlin newspapers and radio cited security officials and witnesses of the shooting, sometimes describing one of the victims as a girl. It was among the darkest periods of the Cold War, with western and Soviet proxies fighting each other for advantage all across the world, each camp accusing the other of violations of human rights and moral corruption.

The death of the two boys was a potential scandal. Adults attempting to surmount the Berlin Wall were fair game for the phalanxes of East German soldiers and border guards safeguarding the perimeter from an elaborate network of watchtowers. But children and pregnant women were off limits.

In subsequent weeks East German authorities attempted to erase not only the memory of the incident, but also of the boys themselves.

Though many heard the stories of two boys shot near the wall on West Berlin radio, most were too afraid to speak out, fearing reprisals. The guards involved in the shooting were sworn to secrecy, according to later court testimony and Stasi documents recovered years after the incident.

But the deaths and the effort to suppress all memory of the killings transformed the lives of those touched by it. Even 30 years after the fall of the wall, an event marked this weekend with celebrations throughout Berlin, the deaths continue to reverberate, serving as a reminder of the cruelty of perhaps the most infamous borders of the 20th century.

“My whole family was taken away from me and I couldn’t say goodbye,” says Annette Moeller, Jorg’s half-sister. “Every day my aunt would come home, I would go out and greet her. One day it wasn’t my aunt. It was a man in a black leather jacket and a black sedan. He said, ‘Get in the car.’”

Berlin is now a unified and thriving city, the capital of Germany, and emerging as a de facto centre of power of Europe as well as an increasingly important global crossroads. But for 44 years following the end of the Second World War, it was a divided city occupied by western powers and the Soviet Union.

West Berlin was an island of capitalism and western culture in the middle of Communist East Germany, and, after attempts to starve it out by the eastern powers failed, it became a conduit for eastern bloc citizens to escape to the west.

Alarmed by the flood of its citizens fleeing into the sectors controlled by the United States, United Kingdom and France, East Germany began erecting a massive wall surrounding West Berlin in 1961.

For foreigners visiting Berlin, the wall became a novelty. The crossing at Checkpoint Charlie became famous in popular culture as a site of espionage and intrigue. But most ordinary people crossed between the two sides via the public transit station at Friedrichstrasse, crossing over the wall and walking through passport control for day-long visits.

For Germans, the wall was brutal and ugly, 96 miles of concrete that cut off subway and tram lines, divided families, and separated friends from each other.

“The wall was a razor blade in the flesh of the people,” says Hans-Peter Spitzner, a former refugee from East Germany. “It symbolised the division of our people. When you looked out on to West Berlin, you realised you were living in a prison and you could see the other side.”

Thirty years ago, Spitzner, a schoolteacher, convinced a US soldier visiting East Berlin to bundle him and his seven-year-old daughter into the boot of his car to make a daring escape attempt to West Berlin.

He made it. He was lucky. Dozens of East Germans were killed trying to cross the wall, or tunnel under it. Many drowned in the Spree river. More were caught and arrested, serving long sentences in prison.

East German authorities immediately attempted to cover up the deaths of Jorg and Lothar. Jorg’s body was cremated and buried before relatives were told of the death; Lothar’s was handed to his parents for burial.

Jorg’s mother Ursula had psychological problems, says his sister Annette, now a 55-year-old retired laboratory technician in Berlin.

Along with another brother named Michael, Annette and Jorg were mostly in the care of their aunt and grandmother. But the death of Jorg worsened her mum’s condition, says Annette.

“It pushed my mother over the edge,” she says. “It definitely worsened her psychological state. After the incident, she was put into a psychiatric institution.”

Apparently worried that Jorg’s relatives might speak out about the killing, East German authorities sought to tear the family apart.

Despite papers granting Jorg’s grandmother, Erna Hartmann, and aunt, Ingrid Schutt, custody of the children, the surviving kids were taken away and put in orphanages.

Annette says she recalls crying and screaming as she was stuffed into a car. Eventually her aunt and grandmother got permission to visit her, but were then permanently barred after trying to take her away.

“I was separated from my mother, grandmother, aunt and brother,” she says. “They stole my childhood.”

After about one and a half years, she was adopted by the family of a member of the East German Communist Party. She says her new parents were loving and kind. But whenever she mentioned that her brother had been killed crossing the wall, she was told to remain silent.

“My new parents told me to keep quiet about it,” she says. “They said I was too young to remember. But I kept saying it: ‘I had a brother who had been killed crossing the wall.’”

Ursula Mariana Mors had a secret. She was Jorg’s primary schoolteacher. And she was immediately suspicious of the official story about his death: Jorg had allegedly drowned in a lake, and Lothar was said to have been electrocuted.

Though Jorg was not the brightest student, Mors happened to know for a fact that he was an excellent swimmer, and wouldn’t have been foolish enough to try to go swimming in a lake in March.

Mors remembers Jorg as a somewhat troubled boy, but quiet and well-behaved. She remembers his blond hair and bright blue eyes, and quite liked him even if he didn’t get the highest marks. She began asking questions about what happened to him, voicing doubts about the official account.

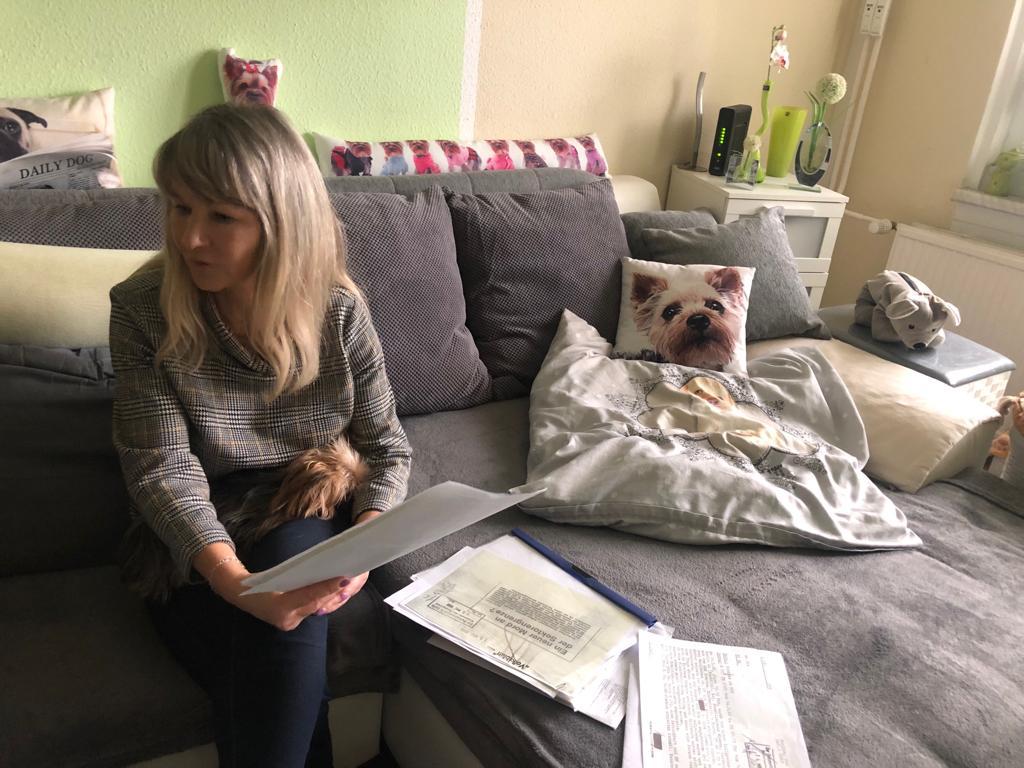

The director of her school summoned her into his office. “He told me, ‘You mustn’t ask questions or say what you know,’” she recalls, during an interview in her apartment in the Steglitz district of Berlin. “‘You must only say he drowned in a lake.’”

The conversation terrified Mors. It was as if they were trying to erase the boy and what happened to him from the annals of time.

She scribbled down everything she knew about the boy on a brown piece of paper: the names of his relatives, what kind of child he was, the grades he achieved at school, the phone numbers of his relatives, and a physical description of him.

“I recorded it all because I knew that one day there would be a prosecution,” she says.

And she and her husband then resolved that they too would escape East Germany. They packed up some belongings and pretended to go on holiday to Hungary. With the brown piece of paper in her belongings, the pair snuck across the border to Austria, and eventually made their way to West Germany, where they rebuilt their lives. Mors remained a schoolteacher, eventually moving back to Berlin.

“If I would have stayed I would have been forced to lie, and I didn’t want to lie,” says Mors. “That meant that I couldn’t be a teacher in East Germany.”

After the wall was opened on the night of 9 November 1989, East and West Germans alike took to it with sledgehammers and pickaxes, seeking to annihilate it. There was joy over the end of the wall, but also rage at what it had done to people’s lives.

Over the years, Jorg’s mother improved and eventually she came to understand what had happened to her boy. She died several years ago. Jorg’s brother Michael died last year at the age of 60. Annette has built her own family, and pictures of her grown children adorn the walls of her small Berlin flat.

In 1997, prosecutors eventually convicted one of Jorg’s shooters, handing him probation. Perhaps ironically, or maybe as a way to repent, after he finished his service in the East German armed forces he began work as a schoolteacher.

Mors keeps a folder with fading articles about Jorg and his fate. Inside is the same brown slip of paper on which she scribbled notes about her pupil and, which she smuggled across the East German frontier. There are copies of speeches she has given about Jorg over the years. A former student of hers once heard her speaking about Jorg on the radio and contacted her, organising a reunion with her and several of his classmates.

Mors asked her former pupils what they remembered about Jorg, and whether they had any pictures. She was stunned that they had nothing. They could not recall him. In the intervening years, none had spoken about Jorg. They had no images of him from class photos.

“Nobody remembered him,” says Mors. “They didn’t know anything about Jorg.”

Told of the recent death of Jorg’s brother, Michael, at 60, she is stunned. He was one of the few people who got to know Jorg during his brief life. “Who lives,” she says, “to remember the dead?”

Dennis Yucel contributed to this report

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks