Basquiat's Paris dream comes true – 22 years too late for him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

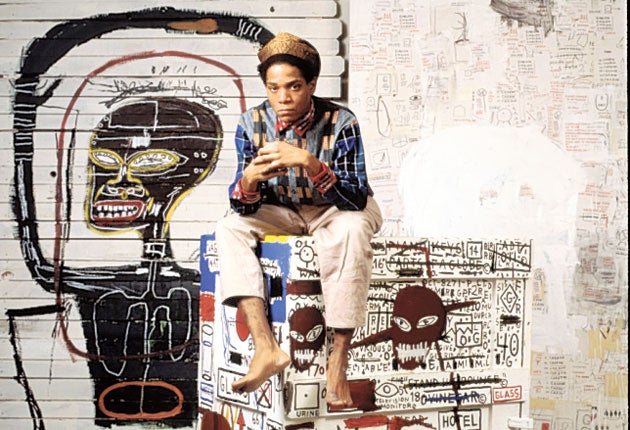

Your support makes all the difference.At the end of Jean-Michel Basquiat's short life, the explosively talented but troubled New York artist had a dream – to stage a major exhibit of his eye-popping, doodle-covered work in Paris.

Nearly 50 years after his birth, and 22 years after his death at the age of 27 of a drug overdose, Basquiat's wish has finally come true.

Basquiat, which opened yesterday at the Modern Art Museum of the City of Paris, brings together more than 150 pieces that trace his rise from graffiti artist to star of the New York art scene.

The son of a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother, Basquiat broke the glass ceiling that had kept black artists out of the art elite. Curators said his dazzling rise helped pave the way for other prominent African-Americans, including President Barack Obama, who was born a year after Basquiat.

"Jean-Michel Basquiat is a very important link in the chain that led to black Americans' liberation," said curator Dieter Buchhart, adding that the artist's grappling with racism was a major theme of his work. "It's overtly political and takes on issues of race and questions capitalism in the boldest ways."

Slave Trade, an oversized 1982 painting featuring a white auctioneer offering a massive skull with a crown of thorns, probes the tragic history of Africans' arrival in the US, while 1983's Undiscovered Genius of the Mississippi Delta skewers the stultifying legacy of segregation. An untitled 1981 canvas features a black man in prison stripes flanked by two white policemen. The officers, hulking shapes in royal blue, wear neat caps, while the prisoner's headgear is more ethereal: a halo.

Basquiat's paintings celebrate icons of black culture, from boxers like Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Robinson and Joe Louis to jazzmen including Miles Davis. Now's the Time, an oversized black wooden disk painted with white lines to suggest a massive LP, is a tribute to Charlie Parker.

It's also among the most sober of the pieces in the Paris show, which explodes with saturated colours, nervous lines and letters and words that – repeated obsessively and sometimes scratched out – crowd the crudely drawn figures. The canvases are palimpsests, piled with layer after layer of acrylic paint and patches of pastel and melded with drawings on paper.

"Basquiat was constantly working and reworking his paintings, adding elements and then painting over them, so that what was there before left just the faintest of traces," said Mr Buchhart, adding that the artist's obsessive, workaholic nature was a source of friction with Andy Warhol, who took Basquiat under his wing in the early 1980s.

The show includes several collaborations between the two, including 1984's Arm and Hammer II, with two huge logos from the baking soda brand side by side. The one on the right – Warhol's – is a faithful reproduction of the iconic logo, with a beefy arm brandishing a hammer, while on the right, Basquiat presents Charlie Parker with a saxophone at his lips as the logo's centrepiece.

"Sometimes the collaborations didn't go so well," Mr Buchhart said. "Sometimes Warhol wasn't so happy because he would paint something and Basquiat would go in and paint over everything. But Basquiat sometimes thought Warhol was lazy because he would finish quickly and Basquiat wanted to go back into everything over and over."

In addition to the paintings, most of them towering canvases and wooden panels, the show also includes unexpected artistic objects, like a painted refrigerator and even a football helmet sprouting a thin moss of human hair.

Mr Buchhart called the show, which runs until January 30, the realisation of Basquiat's last dreams. "I talked to his father, who told me that in the last months of his life, Basquiat talked about wanting a big show in Paris," he said. "We're so glad it's finally happened."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments