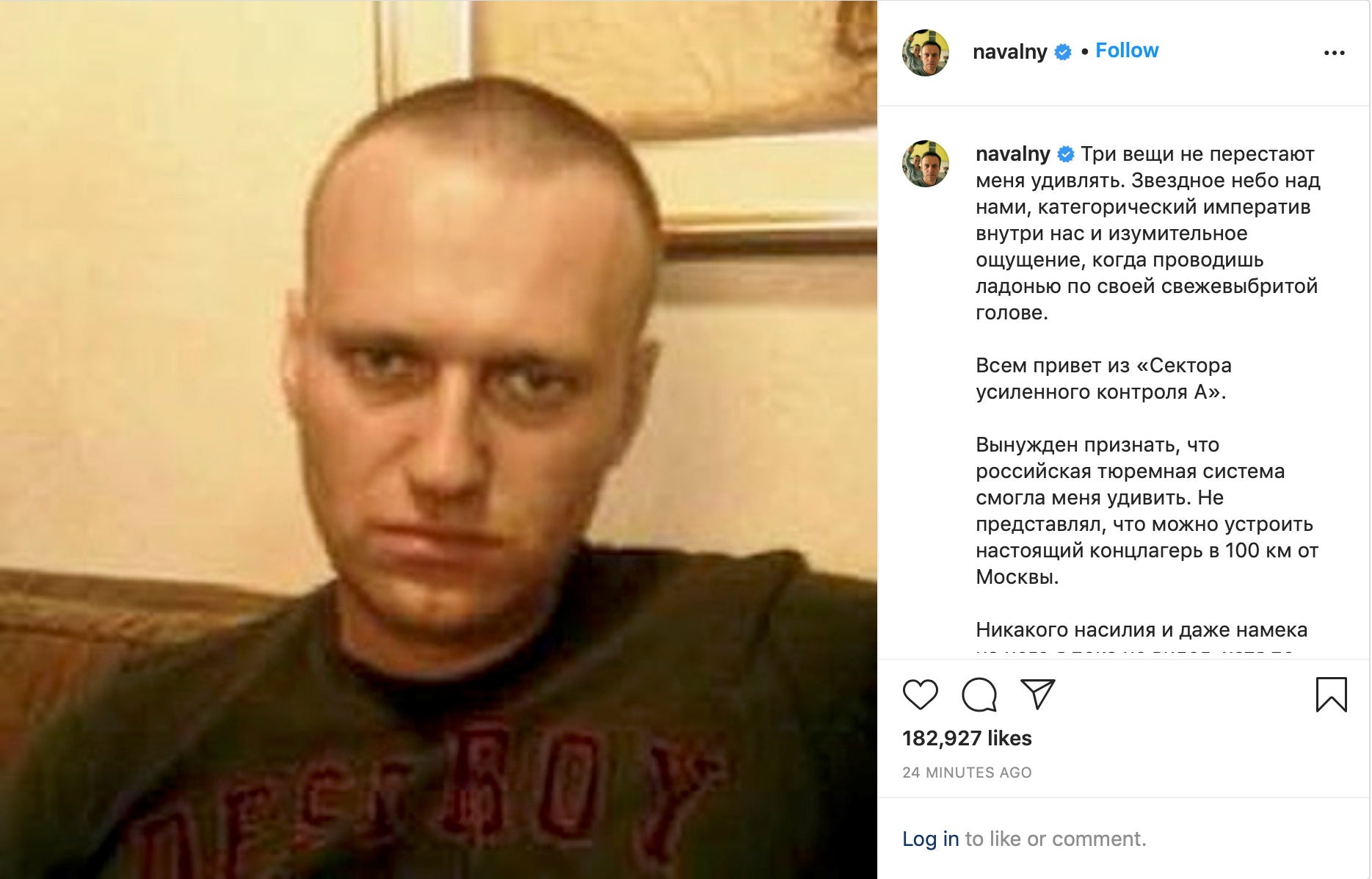

Alexei Navalny writes from new ‘concentration camp’ home

The Kremlin critic also revealed he was woken up ‘every hour’ at night

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alexei Navalny has resurfaced days after going missing within the Russian prison system — confirming his new home as the infamous IK-2 colony in Vladimir region, which he likened to a “concentration camp”.

A social media post in Mr Navalny’s name, apparently dictated to lawyers, described the tough conditions in the prison, including being woken up "every hour" at night on account of him supposedly being a flight risk.

"A man in a pea coat films me and says: ‘2.30 am, prisoner Navalny, removed from preventative risk lists, all in order," the post read. “I calmly go back to sleep with the thought that there are people who still remember about me and will never forget me. Cool, no?”

The post, carried on Instagram and Facebook, compared conditions to those depicted in 1984, George Orwell’s famous dystopian novel.

Prison rules were rigorously observed by cowed prisoners, it read — even in the absence of obvious violence. Inmates stood at attention, “too frightened to even turn their heads,” and in a way that lent credibility to accounts of people “being beaten nearly to death with wooden hammers.”

Read more:

“I must acknowledge that the Russian prison system has managed to surprise me,” Mr Navalny’s post said. “I couldn’t imagine that it was possible to set up a real concentration camp within 100 kilometres from Moscow."

The message confirmed the opposition leader has been been assigned to a high-security section in the prison associated with reports of psychological torture. The section is usually referred to by its acronym Suka, translated into English as “bitch”. Lawyers suggested he would likely be transferred to another part of the colony after completing a two week period in quarantine.

The fiercest critic of Russian president Vladimir Putin, Mr Navalny, 44, was arrested on his return to Russia in January. He had been in Germany for several months receiving treatment after surviving a nerve agent poisoning attempt on his life, which, it has been claimed, was carried out by Russian agents. The Kremlin has denied any involvement in the poisoning, but has also ruled out any criminal investigation.

In February, Mr Navalny was sentenced to two and a half years for supposedly breaking the terms of probation while convalescing in Germany. His whereabouts for much of the period since have been unknown.

The process of newly convicted prisoners being moved around the prison system in stages, usually in overcrowded trains or buses, is a legacy of tsarist and Soviet systems.

In theory, authorities are obliged to inform lawyers and next of kin about the whereabouts of new prisoners. In Mr Navalny’s case, this did not happen — with leaks in state media before today the only clues as to his eventual destination.

The Kremlin critic’s arrest triggered a wave of protests that drew tens of thousands to the streets across Russia. Authorities have detained about 11,000 people, many of whom were fined or given jail terms ranging from seven to 15 days.

Russian officials have dismissed demands from the United States and the European Union to free Mr Navalny and stop the crackdown on his supporters.

Moscow has also rebuffed the European Court of Human Rights’ ruling ordering the Russian government to release him, dismissing the demand as unlawful and "inadmissible" meddling in Russia’s home affairs.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments