Second Skripal suspect likely sent to Salisbury to administer novichok antidote, security sources say

'We know that novichok exposure needs immediate antidote so it makes eminent sense to have a military doctor, who is also a trained GRU operative, who can play his part in the operation'

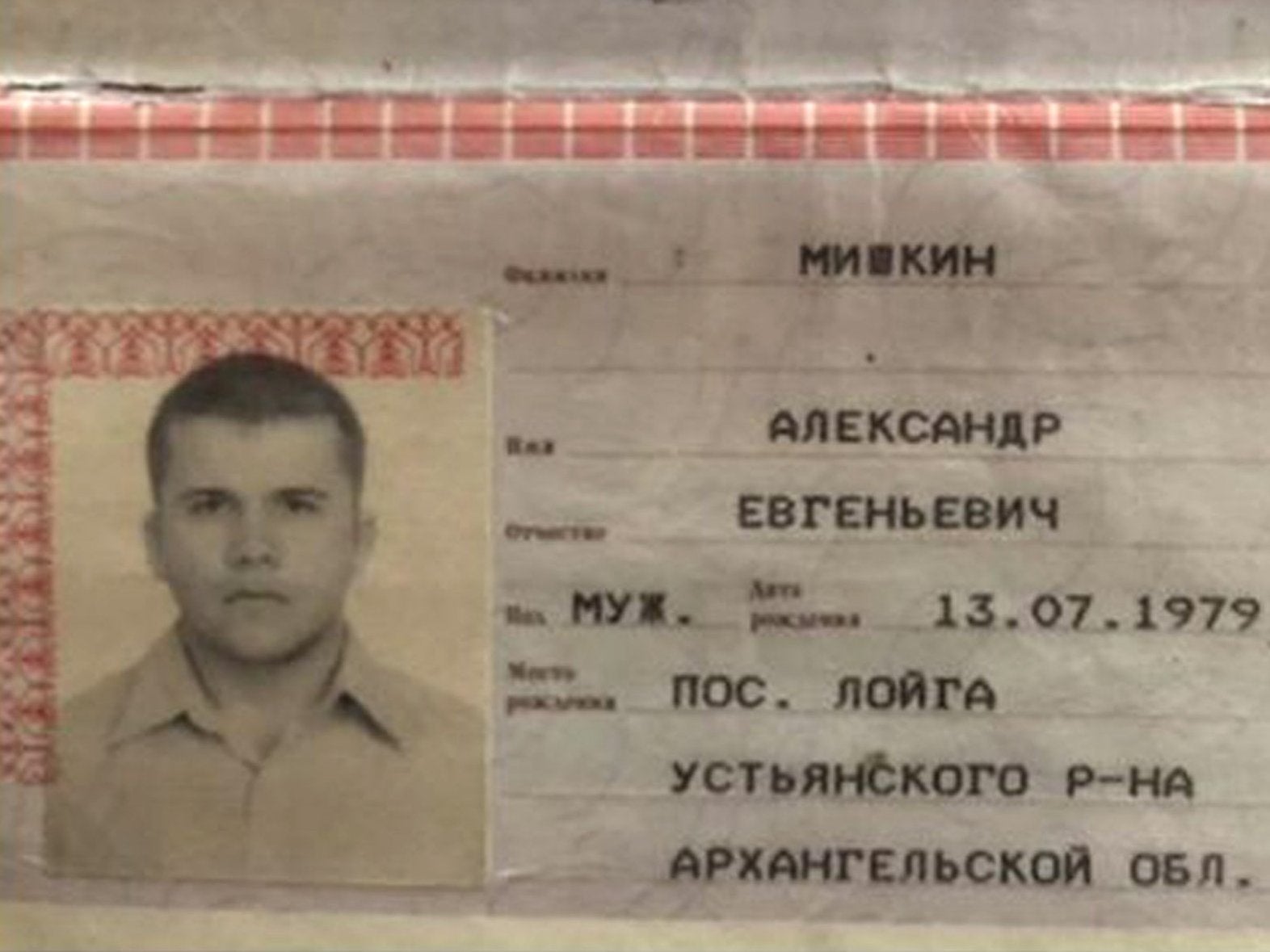

Alexander Mishkin, the second man accused of involvement in the Skripal assassination plot, was likely to have been sent on the mission because he was a trained doctor capable of providing an antidote in case the novichok attack went wrong, according to security sources.

Dr Mishkin, like the GRU colleague who travelled with him to Salisbury, was made a ‘Hero of the Russian Federation’ with Vladimir Putin personally presenting him with the award, according to the investigative website Bellingcat.

But unlike Col Anatolyi Chepiga, who was a member of the Spetnatz special forces, the nature of the services the doctor had provided for the prestigious decoration remains unclear.

Dr Mishkin, who had travelled to Britain on a passport under the name of Alexander Petrov, studied at the Kirov Medical Academy, known in Russian as Voyenmed.

The institute trains medics for the Russian naval forces, and specialised in undersea and hypobaric medicine, a form of treatment for decompression sickness, but also for wounds which do not heal, such as those received from radiation injury.

The relative rarity of novichok, say security officials, meant that the presence of a qualified medic in an operation like the one in Salisbury would have been a very useful precaution.

Pralidoxime Chloride and Atropine are recognised antidotes to nerve agents, but they must be administered within a very short time after exposure to be effective.

Vladimir Uglev, a Russian scientist who was one of the team which had developed novichok at a Russian state facility had previously told The Independent that novichok, depending on the dosage, could be countered with quick use of antidote.

He himself had survived a minor accident with the nerve agent after fast treatment. “I had dropped some on my right arm. I felt irritation on my right arm for five, six years, but that is all,” he recalled.

Dr Mishkin and Col Chepiga could have acquired the antidote after arriving in London. However, there is no evidence, say Whitehall sources, of them meeting anyone or going to a pharmacy, thus the two men were likely to have been carrying it when they travelled to London from Moscow.

There shouldn’t have been any need for a qualified medical person to administer the nerve agent. But there were obvious advantages in having one if something went wrong

“There shouldn’t have been any need for a qualified medical person to administer the nerve agent. But there were obvious advantages in having one if something went wrong,” said a Whitehall official.

“But seeking any medical treatment in case of an accident – inadvertent self-poisoning – would have meant the mission being compromised and would have been incriminating, with very serious consequences: the Moscow link would have been quickly exposed.”

“We know that novichok exposure needs immediate antidote so it makes eminent sense to have a military doctor, who is also a trained GRU operative, who can play his part in the operation and also provide a degree of medical security as well.”

Dr Mishkin, 39 years old, received his award, like Col Chepiga, for services in Ukraine, researchers for Bellingcat were told by neighbours of his family in Loyga, in the Archangelsk District of Northern Russia.

But while Col Chepiga’s decoration is said to have resulted from several specific operations in Crimea where he was serving with the Spetznatz, there is no evidence that Dr Mishkin had been a member of the special forces or had taken part in combat operations.

Researchers for Bellingcat, however, spoke to a source close to Dr Mishkin’s grandmother who stated that the award may have been for his work in arranging the escape of Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine’s pro-Moscow president, following the Maidan protests in 2014.

The grandmother, who is also a doctor, brought up her grandson and is said to have the photograph of him being presented with the ‘Hero’ award by President Putin.

She disappeared from her home three days ago after the website announced that it will be revealing the real identity of ‘Alexander Petrov’.

Bellingcat stated: “The inclusion of a trained military doctor on the team implies that the purpose of the mission has been different from information gathering or other routine espionage activities.”

“Bellingcat contacted various sources with knowledge of practices of Russian military intelligence who provided a range of options on what the relevance of the presence of a doctor in a foreign-operations team means.

“While some stated that the GRU was known to form multi-functional and multi-skilled teams as part of operational ‘best practices,’ others suggested that a doctor would be a mandatory addition to a team tasked with poisoning a target – either for ensuring effective application of the chemical, or to protect team members from accidental self-poisoning.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks