A far-right revolution as regional France opens its doors to a reconstructed National Front

The party set to take half a dozen towns in Sunday’s elections. John Lichfield reports from one - the pretty, hilltop Fréjus

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fréjus is a pretty Roman town on a hill beside the blue Mediterranean. It has winding streets of ochre or pink buildings, low unemployment, a small immigrant population and little crime.

On Sunday, barring a political earthquake, it will elect a far-right mayor, aged 26. Fréjus – conservative, sleepy Fréjus – will become the spearhead of a populist revolution, not just against President François Hollande but against the entire, stumbling, exasperating French ruling class of the centre-left and the centre-right.

Fréjus (pop, 54,000) is one of a half-dozen towns which could be captured by the National Front in the second round of French municipal elections tomorrow. It is one of two large towns where Marine Le Pen’s “reconstructed” and “non-racist” FN – Front National – looks almost certain to win.

Why? And why here? All politics are local. In Fréjus, local quarrels have reinforced national grievances. Like all the 15 towns where the FN topped the first-round poll last weekend, Fréjus is a political basket case.

The town hall has piled up €150m (£124m) of debt. Both its centre-right mayor, Elie Brun, and its most famous political son – the former defence minister, François Léotard – have been convicted of corruption.

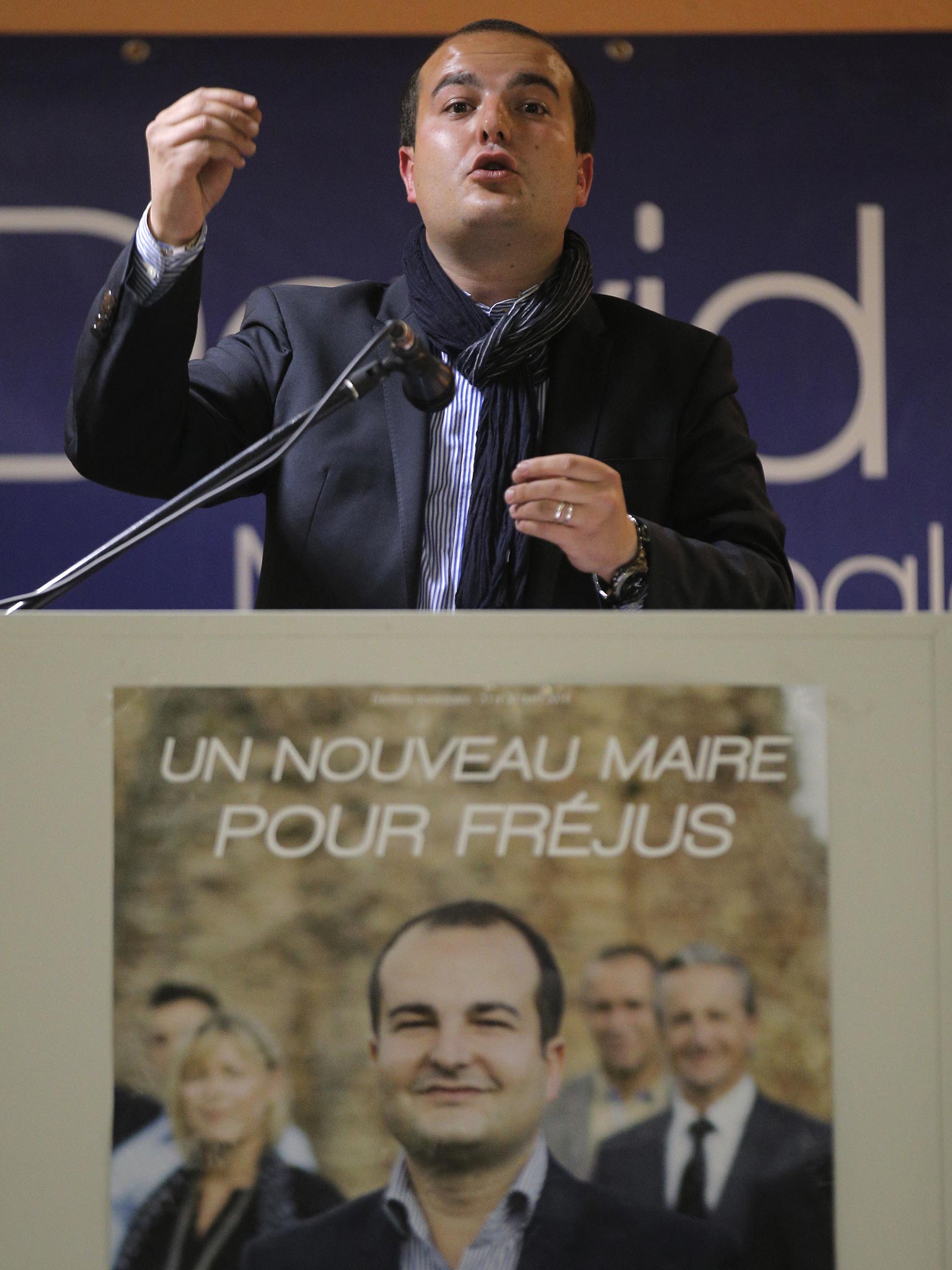

The National Front candidate, David Rachline, tripled the party’s score last Sunday to 40.3 per cent – one of the most striking results on a spectacular day for the French far right.

Mr Rachline is a leading figure in Marine Le Pen’s fumigated and dry-cleaned Front National. He epitomises its new professionalism but also its evasions and its lurking menace.

He is young, intelligent, warm and presentable. He has a charming smile. He is a former head of the FN youth movement. He runs the party’s internet operations. He is 26 but looks, and talks, as though he were 46.

Mr Rachline is half-Jewish. At 15 years old, he joined a party whose founding DNA came from the pre-Nazi tradition of anti-Semitism on the French nationalist right and from the Vichy regime which collaborated with the Nazis to govern southern France from 1940 to 1944. He is one of a small corps of FN elite candidates who have cultivated – in some cases for years – towns badly run by left and right. They have weaved local and national events into a single, persuasive narrative, which goes broadly as follows.

“There is corruption here but also corruption in Paris. Why? Because there is a selfish and self-perpetuating political elite here – but also up there. The left and the centre-right take turns to rule but always with the same failed policies, dictated not by you, the voters, but by Brussels and by the markets.”

Ideology is scarcely mentioned. Mr Rachline prefers to talk about “real problems” – crime, debt, the erosion of tourism, the biggest employer in Fréjus. He speaks about immigration; he criticises plans to build a mosque in Fréjus. In both cases, he speaks no more aggressively than the candidate of the centre-right party, the Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP).

And yet Mr Rachline is reported to be a friend of Alain Soral, the ex-FN, ultra-right polemicist who is the guru of the anti-semitic, black comedian, Dieudonné M’bala M’bala. Alain Soral is viscerally anti-globalist, anti-market, anti-European and anti-American. Above all, he is viscerally anti-Jewish.

Is that not a strange political hero for a half-Jewish man who proclaims himself to be moderate, managerial, French nationalist?

David Rachline told The Independent: “These are appalling calumnies spread by my opponents. Yes, of course I met Alain Soral when he was in National Front. But I have not seen him a single time since he left. I do not share his opinions.”

But how could someone with a Jewish background join a party steeped in anti-Semitism from its birth?

“Look, I was born in 1987, not 1887 or 1947,” he said. “These people who were at the party’s birth mean nothing to me.”

This is disingenuous. The party’s main founder, Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine’s father, has been convicted in France for minimising the Holocaust. He was leader of the FN until 2010, seven years after Mr Rachline joined. Mr Soral left in 2009.

Mr Rachline goes on. “I am not interested in the past. I am interested in the future. So are the people of Fréjus. The vote last Sunday shows that the people here – and throughout France – know that we have been right all along.

“They no longer believe the lies that are told about us by the other parties, which are actually just one party… For years, we have had the same tired, discredited policies, on Europe, on crime, on immigration, on the delocalisation of French industry. Now, in Fréjus and in France, everyone can see the consequences.”

Walking around the streets of Fréjus, the most racist comment that I heard was from an excitable, large woman dressed in red. “Look at him. That Jew,” she said. “I don’t mind a laugh but just look at the Jew with his shiny shoes.”

She was pointing at David Rachline as he crossed the town hall square, shaking hands with everyone he met. The woman turned out to be Jewish, of North African origin. Her friend, Sandrine, also Jewish, said: “Tell the people of Britain that Fréjus is a peaceable, cosmopolitan town. We want to keep it that way. We don’t want a National Front mayor.”

Sandrine blamed last Sunday’s vote on “hundreds of old couples who have bought flats” in the Fréjus-Plage, the newer, richer part of town beside the sea. She defended the outgoing mayor, Elie Brun.

“He may be a little corrupt but, in France, all the politicians are a little corrupt,” she said. “Mr Brun has done a lot for Fréjus and he is a great humanist. He has reached out to all the communities here. He wanted to help the Muslims to build a mosque. That is why many people have turned against him.”

The political script in Fréjus could have been written by Marine Le Pen herself. In January this last year, the long-time centre-right mayor, Mr Brun, was convicted of favouritism in the award of rights to a private beach.

The UMP refused to let him run again under its party label. His long-time ally, Philippe Mougin, was made the official centre-right candidate instead. Mr Brun insisted on running as an independent. The two former friends spent most of the campaign insulting each other.

Last Sunday, Mr Mougin scored 18.85 per cent – less than half the FN score. The outgoing mayor got 17.65 per cent. The Socialist candidate, dragged down by the unpopularity of President Hollande, got a disastrous 15.58 per cent.

The only hope of defeating Mr Rachline on Sunday was a so-called “Republican Front” against the FN, behind a new, compromise mayoral candidate. The Socialist candidate agreed on Tuesday. So did the outgoing mayor. Mr Mougin refused.

And so, on Sunday, selfishly and suicidally, two discredited centre-right candidates will divide the anti-FN vote and virtually ensure Mr Rachline’s victory.

The UMP has been rejoicing in the calamities visited on Mr Hollande last week. The Socialists may lose 100 cities and towns by the time that second round of polling ends on Sunday night.

The lesson of Fréjus is that Marine Le Pen’s respectable-seeming far right is just as much a threat to the UMP – maybe more so – as it is to the left. In Paris, as in Fréjus, the UMP is engaged in a permanent, sterile and selfish battle of egos. Several of its leaders, including former president Nicolas Sarkozy, have been accused of financial irregularity.

President Hollande, meanwhile, two years after his election, has adopted a market-oriented cure for France’s economic ills – but has found no way of selling a narrative of painful reform to his own party, let alone the French people.

Steeve Briois, secretary general of the National Front, who was elected mayor of Hénin-Beaumont near Lille in the first round of elections last week, was in Fréjus yesterday to support Mr Rachline. He told The Independent: “Something has changed. We are no longer seen just as a party of protest. We are seen as the party – the only party – which produces new ideas. People want to see us in power.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments