Schindler's lost list found in Australia

Librarian astonished by discovery of yellowing manuscript

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

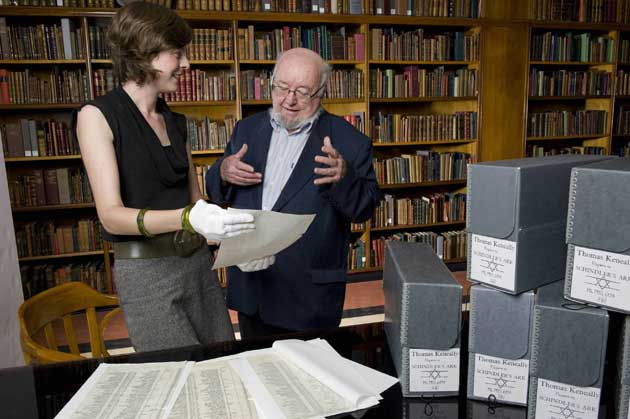

Your support makes all the difference.Poking through boxes of old papers in the vaults of the State Library of New South Wales, historians were astonished to discover a yellowing manuscript containing 801 names. It was a document laden with significance for the history of the 20th century: Schindler's list.

The closely typed, 13-page list was drawn up by a German industrialist, Oskar Schindler, who risked his life to save about 1,200 Jews from the gas chambers. Little was known about his heroic deeds until the publication in 1982 of Schindler's Ark, by the Australian author Thomas Keneally, which was turned into the Oscar-winning movie, Schindler's List, directed by Steven Spielberg.

Keneally wrote his book following a chance encounter with Leonard Pfefferberg, a Polish Jew who owed his survival to Schindler. The author had gone into Pfefferberg's Beverley Hills boutique to buy a new briefcase; the shop owner, learning that Keneally was an author, showed him his copy of the list, part of an extensive archive he kept on his saviour. Keneally was hooked.

But after publishing the story under the title Schindler's Ark, which won the Booker Prize in 1982, the writer sold the document, along with other research papers, to a manuscript dealer. Eventually, the list – a carbon typescript copy – found its way into the State Library in Sydney, which bought six cartons of Keneally's papers from the dealer in 1996.

It was recently discovered sandwiched between German newspaper clippings and the author's own research notes, according to Olwen Pryke, the library's co-curator. Only a few copies of the original lists, which were compiled by Schindler in an effort to persuade the Nazis to save his Jewish workers, have survived. One is housed in Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial museum in Jerusalem.

Dr Pryke was amazed to stumble across the list, which she called "one of the most powerful documents of the 20th century", in one of the boxes. "This list was hurriedly typed on 18 April 1945, in the closing days of the Second World War, and it saved 801 men from the gas chambers," she said. "It's an incredibly moving piece of history." Schindler was a Nazi party member, war profiteer and hard-drinking womaniser who used hundreds of Jews as forced labour at his enamelware and munitions factories.

Conscience-stricken after witnessing a raid on the Krakow Ghetto in Poland, he used his charm and guile to persuade officials that his workers were vital to the war effort, even plying high-ranking SS officers with money and alcohol. His list, written in German, sets out the names, nationalities, religion, birthdates and skills of the Jews he employed as mechanics and metalworkers. Pfefferberg, who urged Keneally to tell their remarkable story, was worker number 173. His wife, Ludmilla, was also saved.

Recalling his 1980 encounter with Pfefferberg, Keneally told the Sun Herald newspaper: "It's the only case in my lifetime that someone has said 'I've got a great story for you' where I've ended up doing anything about it."

The author added: "Writing so many books is not only a great weariness to the soul, it's also a storage problem. But I'm very glad the list has ended up at the State Library."

Schindler, played by Liam Neeson in Spielberg's 1993 film, was almost penniless by the end of the war. He died in Germany in 1974. He and his wife, Emilie, were later honoured at the Yad Vashem as among the non-Jews who risked their lives to save some of Europe's Jews from genocide.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments