A history of the haka, from Maori warriors staring down death to the mighty All Blacks

Ceremonial dance associated with New Zealand’s all-conquering international rugby side traces origins through the centuries and expresses strength, unity and defiance

A UK-New Zealand free trade deal agreed in October between Boris Johnson and Jacinda Ardern’s administrations contained an unusual provision alongside its pledges to ease market access for one another’s export products.

The pact between London and Auckland included a commitment by Britain to support its ally in the southern hemisphere in identifying “appropriate ways to advance recognition and protection of the haka ‘Ka Mate’” and to acknowledge the leaders of the Ngati Toa tribe as custodians of the traditional Maori ceremonial dance.

The tribe’s guardianship of “Ka Mate” - famously performed by New Zealand’s all-conquering All Blacks rugby team before each match - was acknowledged in New Zealand law in 2014, when it was formally recognised as a “taonga” or national treasure, but concerns have grown more recently about the haka being misused and disrespected overseas.

The ritual has been ill-advisedly mimicked by a Czech dance troupe on TikTok, spoofed by drunken oafs on London pub crawls and recreated by a team of British NHS nurses in facepaint at the start of the coronavirus pandemic last April in a misguided expression of team spirit.

Media coverage of the latter incident prompted New Zealand academic and activist Karaitiana Taiuru to call out the performance as an act of cultural appropriation and an apology to be issued.

Mr Taiuru has reacted positively to the recognition of the haka in the new trade deal, saying: “I hope that this was a good step forward for recognition of Indigenous rights.”

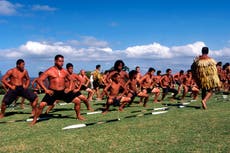

Most foreigners first encounter the haka through the All Blacks, who make for an intimidating spectacle as they stare down their opponents with intense, glaring eyes and protruding tongues, pounding their thighs and forearms as a designated leader issues war cries demanding togetherness, strength and courage from his compatriots as they prepare to face an enemy they will almost certainly vanquish.

“Ka Mate” (meaning literally, “It is death”), the haka most commonly performed by the men’s squad, is just one of many variations of a custom dating back centuries that might equally be performed at weddings, funerals or other public ceremonies, as often an expression of welcome or community pride as it is a war dance to warn off would-be foes.

The women’s rugby team, the Black Fearns, incidentally, have their own haka, “Ko Uhia Mai” (or, “Let it be known”).

In Maori legend, the origins of the ritual lie in a dance celebrating life itself.

Tane-rone, the son of the sun god, Tama-nui-to-ra, danced for his mother Hine-raumati, the summer maid, and became the trembling of the air seen on the horizon during sweltering days, a presence represented in the haka by the participants quivering their hands.

“Ka Mate” was composed by the Ngati Toa chief Te Rauparaha in 1820, a man “born into a life of turmoil”, according to 21st century elder Hohepa Potini, who sought to summon the spirit of his ancestors to inspire his warriors at a moment when the tribe was on the brink of extermination in a feud with its enemies.

“It’s talking about the triumph of life over death,” Mr Potini explains.

According to Timoti Karetu’s 1993 history Haka!, English naturalist Joseph Banks witnessed an earlier variation when he visited New Zealand with Captain James Cook in 1767.

"The War Song and dance consists of Various contortions of the limbs during which the tongue is frequently thrust out incredibly far and the orbits of the eyes enlarged so much that a circle of white is distinctly seen round the Iris: in short nothing is omittd which can render a human shape frightful and deformd, which I suppose they think terrible,” Banks noted.

With New Zealand under British colonial rule in the 19th century, Christian missionaries like Henry Williams attempted to eradicate the haka and “waiata” (traditional chants) and interest the Maoris in sedate hymns and Bible study instead, without much success.

The arrival of the Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Alfred, in 1869 brought an end to that campaign when he was greeted at Wellington harbour by tribespeople performing an energetic haka of welcome, impressing the royal and his fellow dignitaries.

The haka began its international association with rugby in 1888 when a team of “New Zealand Natives” led by Joseph Warbrick undertook a lengthy tour of Britain, Ireland and Australia and performed one before their matches, playing a gruelling 107 games and winning no fewer than 78.

Since 1905, “Ka Mate” has been performed before almost every All Blacks match, with the ritual making its debut at the inaugural Rugby World Cup in 1987, when New Zealand thrashed Italy 70-6 in their first group game at Eden Park in Auckland, going on to storm the tournament.

Players like Jonah Lomu would subsequently become celebrated not just for their barnstorming performances on the field but for the intensity of their passion in the haka, his example since passed on to such fearsome competitors as Tana Umaga, Richie McCaw, Dan Carter, Keiran Reed, Ma’a Nonu, Jerome Kaino, Sonny Bill Williamson and TJ Perenara.

While “Ka Mate” remains the standard haka for the men’s side, a new composition, “Kapa O Pango”, was introduced in August 2005 as a “younger brother” the team could call on at their discretion.

It was created specifically to reflect the side’s glorious sporting history by Derek Lardelli, an expert in Maori culture from the Ngati Porou tribe.

“It’s ceremonial, it’s about building your spiritual, physical and your intellectual capacity prior to doing something very important,” he said of its intention, explaining that the gestures involved in the new haka convey the experience of seizing control of spiritual energy, drawing it through the vital organs of the body and expelling it through the mouth, revitalising and focusing the player before kickoff.

Other Pacific Island teams have their own equivalent tribal dances performed before games, including Tonga’s “Sipi Tua”, Samoa’s “Manu Siva Tau” and Fiji’s “Cibi”, but none strike fear into the heart quite like the All Blacks’ ritual.

Away from the game, the haka has occasionally been cause for division, notably when engineering students at the University of Auckland carried out a sexualised parody of it on campus in 1979 and provoked an angry protest, but it is more often than not a uniquely unifying force in New Zealand society, a bond with the proud warrior traditions of the past and a pledge to honour the values of that noble ancestry.

Its performance by school children in the aftermath of the Christchurch mosque shootings in March 2019 is perhaps the ultimate example: a community coming together to honour its dead and express a defiant and undaunted spirit of unity in the face of senseless hatred.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks