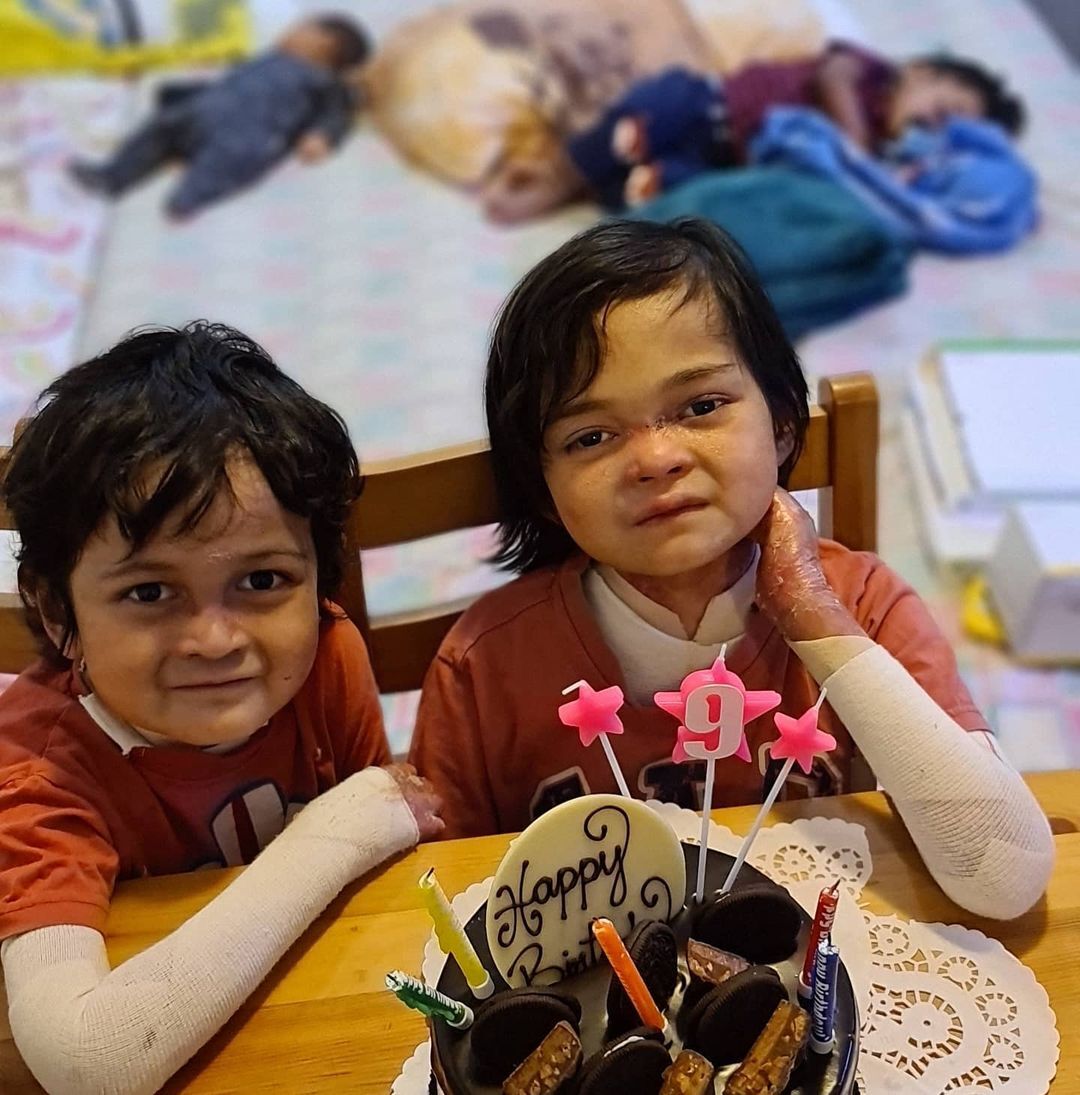

Mother’s fears for her ‘butterfly’ children with skin so fragile it can peel off bumping into strangers

Mum from Sydney is often asked if she set fire or poured hot water on her children

A mother of two children with a rare skin disorder has revealed she is terrified their skin will shred if they bump into strangers in public.

Stay at home mum, Kida Azny, 36, from Sydney, Australia lives in constant fear for her children who were born without most of their skin and with their flesh exposed raw.

Days after the birth of her first daughter with husband Mohd Aidil Aiman, 35, the now ten-year-old was diagnosed with the rare genetic skin condition Epidermolysis bullosa (EB).

Children like Nur Siddiqah and younger brother Muhammad Azraqee, 8 have been dubbed ‘butterfly’ babies because their skin can be as fragile as butterfly wings. They inherited the EB gene from both their parents who were unknown carriers.

Azny said: “Sometimes they wake up screaming at night from the pain they are in, or they can choke on their food while eating because EB affects their food pipe as well.”

EB affects 1 in 50,000 children and is the name for a group of rare inherited disorders that cause the skin to become very fragile, resulting in painful blisters if there is any trauma or friction to the skin.

The family used to live in Malaysia, where Azny felt there was less understanding of the children’s skin disorder. “I often had people asking me if I threw hot water on my children or set them on fire,” she said.

She added that the mental toll of EB is just as difficult as the physical struggle. The children have to wake up three hours before school to begin the “painful” process of bandaging their skin, which they have to repeat after school.

She said: “They always get freaked out in public, because if someone bumps into them it can literally peel their skin off.”

But the siblings confide and help each other through “the anxiety they have over their shared symptoms” as Azny said she wants to help as much as she can but she does not know “what having EB feels like”.

She said: “It much easier to treat their EB now than when they were babies, as now they can actually tell us what they need.

“If one of them is having a hard time the other will jump in and just let us know what will help which actually makes it much easier for us.”

The family- who also have two children without EB- said they received tremendous support from DEBRA Australia, a not-for-profit organisation who support those with EB.

However, Azny believes more can be done to raise awareness for those living with the rare skin condition, and to “teach people about the hardship and damage EB does to so many children around the world”.

To find out more, visit https://www.debra.org.au/about-us/

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks