Cannibalism and calculation: a dark story from the white continent

An Antarctic explorer may have nasty secrets, writes Kathy Marks in Sydney

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

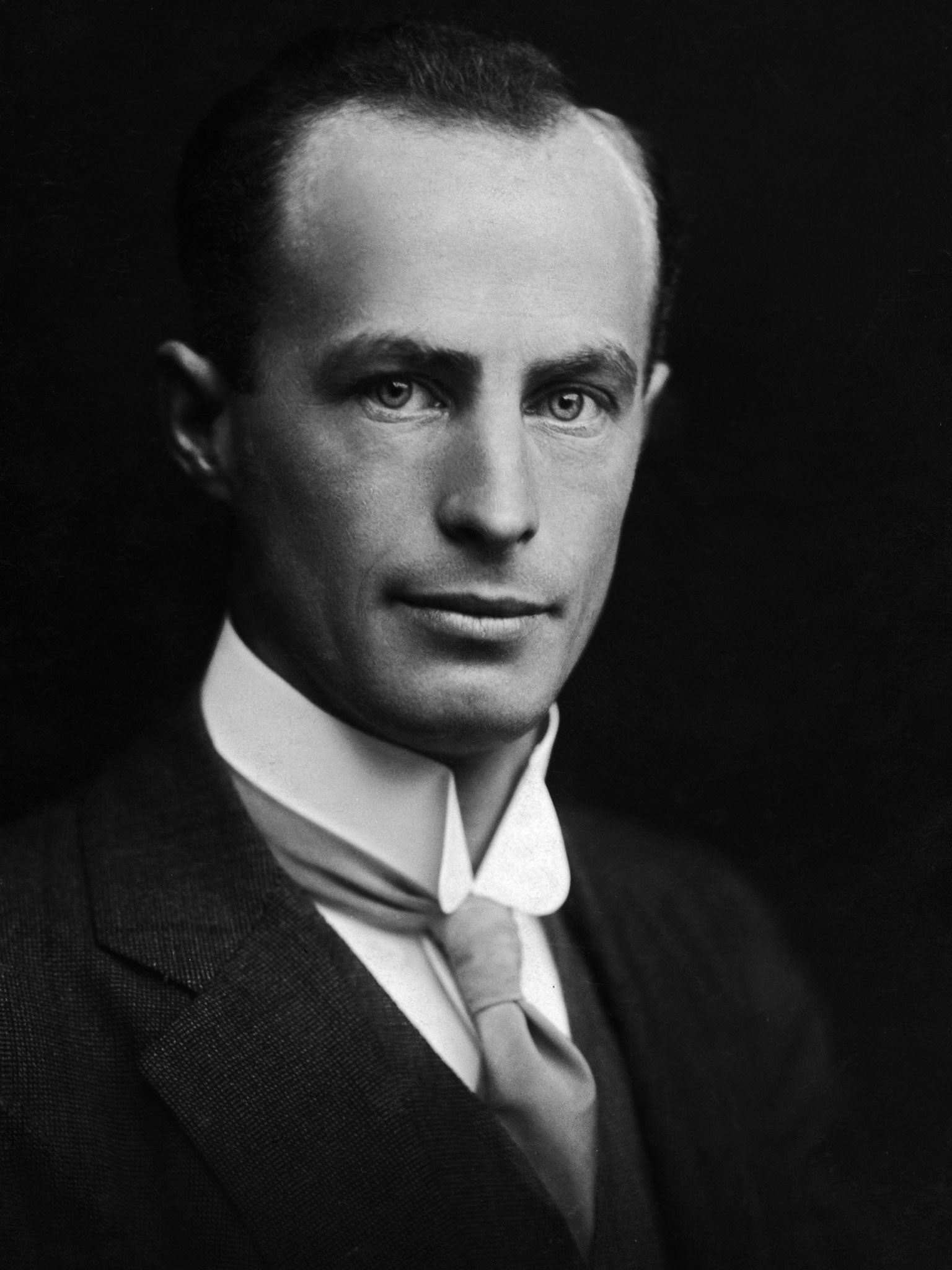

Your support makes all the difference.Stumbling back to base, emaciated and frostbitten, in February 1913, the celebrated Australian Antarctic explorer Douglas Mawson had a terrible story to tell.

One of his team members, Belgrave Ninnis, had fallen to his death down a deep crevasse; the other, Xavier Mertz, had died from starvation and exposure.

Yorkshire-born Mawson, who had struggled on alone for a month through blizzards and thick snow, was lauded for this extraordinary feat of survival. But the real story behind it may have been much darker, according to a new book by an award-wining historian, David Day, who suggests Mawson deliberately starved Mertz to death – and then boiled up his flesh and ate it.

Day also claims Mawson had a torrid affair in wartime London with the widow of his erstwhile bitter rival, the British explorer Sir Robert Scott, while his wife and young daughter waited for him back in Australia. And he brands the legendary explorer a coward who dodged active service while urging young men to join up.

Mawson – whose family moved to Sydney when he was young – first tasted Antarctica as a member of Ernest Shackleton’s 1907-09 expedition. In 1911 he became the first Australian to lead an expedition to the frozen continent. Unlike Shackleton, he was not a natural leader, according to Day, who paints him as aloof and dour, unpopular with his men.

The expedition split into five parties, with Ninnis, a young British soldier, and Mertz, a Swiss former ski champion, accompanying Mawson. Five weeks in, and 300 miles from base, Ninnis fell down the snow-covered crevasse, taking six husky dogs, a tent and a sled containing most of their food with him.

As he and Mertz began the long trek back, Mawson drastically cut their rations. In Flaws In The Ice: In Search of Douglas Mawson, to be published in Britain next year, Day suggests the move may have been prompted by “the hope that Mertz would die before he did and that Mawson might then survive on the remaining rations”.

He asks: “Had Mawson come to the terrible conclusion that there was only sufficient food for one of them to get back to the hut [at base] alive? Did Mawson’s experience … give him confidence that he could endure starvation rations much better than Mertz?”

Mertz did succumb, leaving Mawson to cover the final stretch alone. Before heading off, he recorded in his diary that he “boiled all the rest of [the] dog meat”. Mertz, though, had shot the last dog two weeks earlier, suggesting it was unlikely there was any meat left.

“Might it have been something else that he was cooking?” asks the author. Had Mawson “taken the opportunity to boil some of Mertz’s flesh so that he would have a greater chance of making it back alive?” (In 1915, a US journalist reported that Mawson had told him he had considered eating Mertz but decided against it, as it “would always leave a bad taste in my mouth”. Mawson denied ever saying that.)

Although the expedition mapped large swathes of the Antarctic coastline, it was overshadowed by the race to the South Pole by Scott and Roald Amundsen, and by the outbreak of war.

Day claims that, despite spearheading a conscription drive in Australia, Mawson was reluctant to join up himself. Posted to the War Office in London in 1916, he enjoyed a “mad summer of love” with the beguiling Kathleen Scott, whose army of admirers included Prime Minister Herbert Asquith.

Not surprisingly, the book has drawn criticism from Mawson’s descendants, as well as from modern-day polar explorers.

Tim Jarvis, who retraced Mawson’s journey in 2007, told Australian media it is “very easy … with 100 years of hindsight to criticise these men”. Mawson’s great-granddaughter, Emma McEwin, said she was unconvinced by claims of an affair.

The book details numerous “misjudgements and miscalculations and blind spots ” on Mawson’s part.

Day told The Independent that the explorer was “lucky to get away with losing only two men... it could very easily have been much, much worse.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments