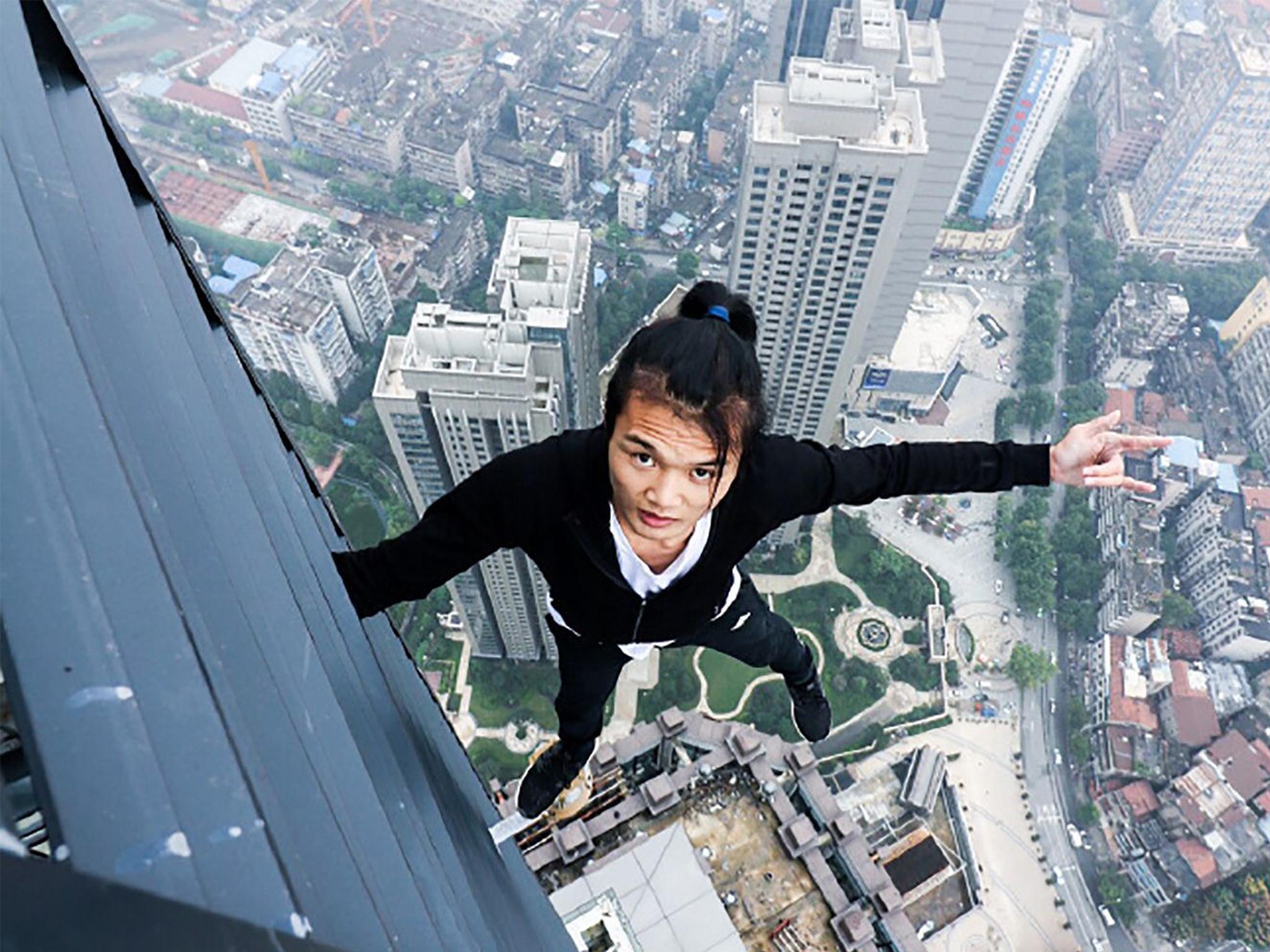

Wu Yongning: Chinese daredevil's death in fall from skyscraper puts spotlight on dangerous 'rooftopping' trend

His family say he dangled himself from the building for a video he hoped would earn as much as $15,000 if it went viral — money he would use to get married and pay his mother’s medical bills

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For months, Wu Yongning had climbed towers and buildings high above the streets of cities in China, turning a camera on himself as he teetered on ledges or clutched an antenna with one hand.

Through his dizzying lens, he became a celebrity for his high-altitude stunts, amassing thousands of followers on Weibo, the Chinese microblogging site.

But on 8 November, his online posts suddenly stopped.

That was when, the police in China now confirm, Wu fell to his death from the top of the Huayuan Hua Center, a building more than 60 storeys high, in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province, Chinese media reports said recently. This week, a video of his fall was posted online and widely shared.

The young man’s death exemplified, again, the internet obsession of inviting millions of strangers to witness a life, in all its perils, pranks and failures.

It also shed light on the thrill-seeking subculture associated with rooftopping, in which ambitious daredevils scale skyscrapers around the world and take selfies against magnificent views above the tops of cities, from New York to Dubai to Russia.

In China, Wu’s death prompted the official media to warn about livestreaming stunts. “By climbing on high buildings without taking any safety measures, Wu put himself in danger and pushed himself to his limits, but that does not mean what he did is a sport,” a report in the China Daily said on Tuesday.

Wu’s family told the Xiaoxiang Morning Post, a newspaper based in Changsha, that the young man, who had worked as a film extra, had dangled himself from the building for a video he hoped would earn as much as $15,000 if it went viral — money he would use to get married and pay his mother’s medical bills.

An excerpt from the video of Wu’s last moments shows him on top of the building, clad in black with his hair pulled back from his face, meticulously and repeatedly wiping the ledge. He swung his legs over the edge and partially hung there, clutching it with the full length of his arms, before pulling himself up and sitting down to wipe the edge again.

Then he swung his legs over one by one for a final time. He did two pullups into the void, gripping the ledge. Attempting a third, he appeared to struggle, trying to find a hold with one foot after the other. A small sound resembling a human voice, perhaps a whimper, can be heard on the recording. Then he dropped.

His death resounded in the community of people who seek urban altitudes for thrills, curiosity or profit.

Daniel Cheong, 55, a professional cityscape photographer who lives in Dubai, home of some of the world’s tallest skyscrapers, said that when he moved to the emirate in 2008 there was a small, informal group of rooftoppers who found each other on social media through their photographs.

“There are different flavours - those who are doing it for the pure purpose of cityscape photography and those who are doing it for the thrill to post on Instagram and YouTube,” he said in a telephone interview on Wednesday.

Mr Cheong, who has a photography business in Dubai through which he gains access to rooftops legally, said that he has been on roofs as high as 100 floors up, fixing his camera equipment to a safety leash. On some rooftops, there is nothing to stop a person from going over the edge, he said.

“The goal is to capture the cityscape,” he said. “The attraction really has nothing to do with the fact that you go to the 100th floor. It is purely for composition.”

But he said informal bands of rooftoppers, many of them Russian, are seeking to build online networks of followers on YouTube and Instagram, and hopefully, a lucrative deal out of advertisements.

Such thrill-seekers, he said, “mostly have a reputation for sneaking illegally on rooftops to get selfies. It is more the thrill of getting very high.”

Neil Ta, a photographer in Toronto, took up rooftopping in 2009 to fulfil an aesthetic curiosity, climbing to the tops of tall buildings in Canada and during his travels in Southeast Asia for the view.

“The reality of it is not everyone is going up there and prancing on the ledges and being irresponsible,” he said in an interview on Thursday. “There are a lot of people going up there and looking at the city from a safe distance from the ledge.”

But Mr Ta said he became disillusioned with the changing nature of the skyscraper adventures over the years. Instagram grew more popular for recording mischief-making and feats of daring. Security was enhanced in high places, and gaining access to roofs of skyscrapers became more difficult.

Where once he persisted through the challenges of scouting locations with unlocked rooftops, Ta began to notice “a newer breed of rooftopper” who did not hesitate to use a crowbar or bolt cutter. He quit rooftopping in 2014.

“There was no art left in the process,” he wrote in a farewell blog post that year. “No subtlety.”

Mr Ta said on Thursday that he sympathised with Wu, however. “He was doing it to win a prize. I could see why he would want to do that to provide for his family. So I can’t really fault him.”

New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments