The hot list: China's cultural movers and shakers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference. The musician

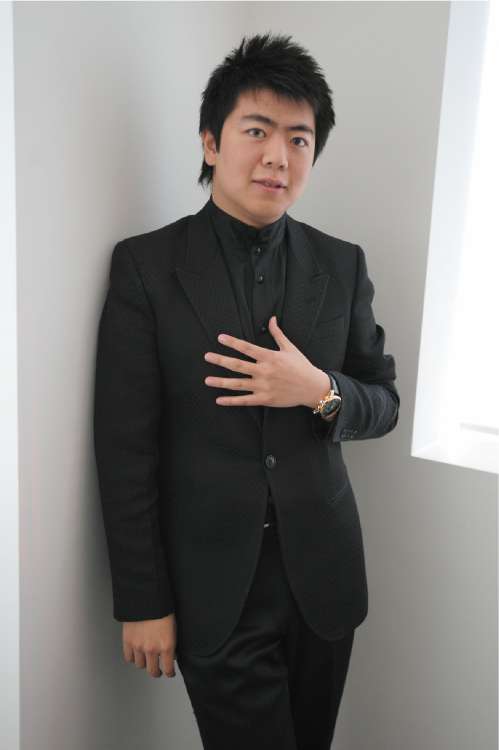

Lang Lang

Whatever else happens at the opening ceremony for the Beijing Olympics, and whoever does or doesn't boycott it, one near-certain thing is that at some point a piano will be wheeled into the stadium for a short, but seismic performance by a young man with tsunami hair, a faraway look and forearms like industrial pistons.

What exactly he'll be playing is, he says, "a surprise": probably something Chinese that sounds like Rachmaninov. But in any event, the chances of reaching the end of it before his audience breaks into rapturous applause are not great. Chinese audiences haven't as yet learnt the Western art of restraint when it comes to classical music. Nor have they learnt the difference between Lang Lang and a pop star: a confusion he doesn't discourage.

Lang Lang is a big name in the West where, as the hot commercial property on the piano circuit, he gets everything from South Bank Show profiles to guest turns on Sesame Street. But in China he's almost a religion, with a following in numbers that barely fit a Western mindset. Most of them adolescent.

In China, depending on which of the estimates you believe, there are said to be as many as 30 million children learning the piano, driven by ambitious parents for whom pianos represent the Everest of cultural sophistication. At weekends they throng establishments like Jiangjie Piano City, a battery farm for young players with 12,000 students – each one packed into a sound-proofed cubicle containing a keyboard, a coat-hook and a lot of tension. And what these armies of children have in common, apart from sore fingers, is that they all want to be Lang Lang.

Ask Lang Lang about this and with the wisdom of a 25-year-old he'll tell you how important it is to encourage the young, to be a good role model for his people, a worthy ambassador for China, etc etc. Which he certainly is. But he'll tell you this in a voice whose Chinese accent comes wrapped in American. And the truth is, America has been the centre of his life since he was sent there to study at 14. His main home these days is New York, though he calls himself "a citizen of the world. I live out of suitcases. Musicians do."

Lang Lang's suitcases get more wear than most. His playing schedule is absurd – around 130 concerts a year generating a carbon footprint the size of several airports as he shifts relentlessly between Chicago, London, Munich, Tokyo ... mostly one-night stands. Through sheer turnover of work he is reportedly the highest-earning pianist alive. And if nothing else, he's been able to pay back his parents for the hardships they bore to get his career off the ground. With interest.

Lang Lang (the name means "Brilliant man") was born in 1982 into a lower-middle-class family from provincial Manchuria in China's north-east. It was a time when a whole generation of musicians stifled by the Cultural Revolution were suddenly free to grasp for their children what they themselves had been denied. And Lang Lang's father, a musician, was very determined.

Aged three, Lang was bought a piano "with money borrowed from my grandmother because it cost half a year's salary". Aged nine, his father took him on the 11-hour journey to Beijing to enrol in the Central Conservatory there – a move that split the family, with father and son living squalidly in the big city while the mother stayed in Manchuria, trying to earn enough to support them.

In 1996 his father took him to America for further studies. Three years later he stepped in at the last minute to replace a sick pianist at a Chicago Symphony concert and made headlines. Then came Carnegie Hall, a contract with Deutsche Grammophon (who market him like no other pianist on their label), and the phenomenal career he now enjoys.

But whether he's more than a phenomenon – and actually a good musician – is debatable. He's an extraordinary communicator, big on energy and personality. And at his best, careering through the great warhorse concertos with exhilarating power, it's a great show. But it's also brash, like keyboard semaphore. With shiny suits and gelled hair, he's the Liberace of the concert platform.

To be fair, he isn't only loved by Chinese teenagers: he has serious supporters too, like Daniel Barenboim, who clears space in his diary every couple of months to act as Lang Lang's mentor. Then there are the orchestras who book him for concerto dates. Next year he'll be "in residence" with the London Symphony, whose chief executive, Kathryn McDowell, believes in him – but as a developing genius in need of guidance. "So far," she says, "I think he's had some bad advice."

In recent years he's also become what's charmingly called a "brand ambassador" for Rolex watches, Montblanc pens, Panasonic and, now, Sony. All these companies are using him to sell into the gold-mine of a Chinese market poised to become the world's largest consumer of luxury goods. But suggest to him that, maybe his priorities are veering toward merchandising rather than music, and you get a sharp response: "This is wrong thinking," he says. "I am totally a musician. But classical music has to wake up and be realistic – we're not in the 18th century. These companies pay for my tours, what's wrong with that?"

Well, I suggest, you wouldn't find Alfred Brendel selling pens. "But he's a different generation – look how old he is. I respect his playing, but I don't want to be Alfred Brendel. We have different ways."

It's tempting to attribute Lang Lang's different ways not only to his youth but to his background. He belongs to a generation of newly liberated Chinese making up for lost time and not too worried about seeming brazen. As such, he's very much his country's new face – which is why he finds himself, now, working as a double-agent: not just selling the West to China, but selling China to the West.

He denies political connections, but the Beijing hierarchy has seized on him as useful: hence his presence at events like the opening of the new £180m Beijing arts complex that sits like a giant steel slug (though locals prefer to call it "the egg") near the city centre. He appears in promotional films for China. And, of course, there's the Olympics – where he risks involvement in a can of worms but won't be drawn on the subject beyond describing the recent protests as "unfortunate".

But distancing himself from politics, he's happy to be thought a "cultural ambassador" for China. He uses the phrase a lot. And it's why he's not happy that a scheduled, pre-Olympics world tour with the China Philharmonic has just been cancelled – supposedly for money reasons although some say otherwise. When venues have asked him to fill in with solo recitals, he's refused. "Why should I?" he says. "This was for the orchestra, not me, to show people how we make music in China."

As it happens, though, the world is only too aware of how they make music in China. Things have moved fast since the Cultural Revolution. There are now more than 30 full-time symphony orchestras, with glittering new concert halls for them to play in. Chinese conservatoires churn out singers for the world's opera houses. And by claiming as its own ex-pats such as Lang Lang, on the grounds of race rather than residence, China can say it fields at least one superstar in most departments of the Western classical tradition. More significantly, as that tradition struggles to keep going, it sees China as the future: in the form of those 30 million piano-playing, CD-buying, Lang Lang-loving adolescents.

As he says with pride, "They see me on TV, on YouTube, and they like it. At my concerts in Beijing, thousands in the audience, 90 per cent under 21. In London or New York, 90 per cent over 60. Think of that." We do.

The model

Du Juan

In the recent rumpus about supposed prejudice among fashion labels against black models, there was little mention of those hailing from China. When did a Chinese model last grace the cover of, say, French Vogue? Well, it was back in October 2005 but even then it was to front a Shanghai special (and the model played second-fiddle to the Australian Gemma Ward). Still, if you were going to bet on one Chinese model cutting through the "silk curtain", it would be Ward's co-poser, Du Juan. The willowy, Shanghai-born former ballerina first walked down a catwalk five years ago, when her towering height – she's 5ft 11ins – lead her from the barre to the runway as friends persuaded her to enter a national modelling contest. She won, and by 2006, Style.com (the online home of Vogue) had declared her one of the Top 10 models to watch. Du's CV now reads like a fashionista's Most Wanted list, boasting shoots with the likes of Mario Testino and Juergen Teller, and runway appearances for Louis Vuitton, Yves Saint Laurent, Roberto Cavalli and Hermès. Du Juan, now 25, also fronts international campaigns for the likes of Gap and Benetton.

The actor

Zhang Hanyu

China's movie Hall of Fame is piled high with kung-fu screen idols, from Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan to Chow Yun-Fat and Jet Li, but a new generation of actors is emerging that offers more than death- defying stunts and stilted dialogue. Leading the charge is Zhang Hanyu, a one-time dubber who made it big last year in the Chinese blockbuster Assembly, which was released to critical acclaim in the UK in March this year. The potent anti-war epic saw Zhang play Gu-zidi, a Communist captain during China's brutal civil war in the 1940s, who leads his dwindling battalion into a series of ferocious battles only to see the sacrifices of his fallen comrades ignored once the fighting ends. Zhang's thoughtful performance won him plaudits at home and abroad and helped invigorate a fledgling career that started at Beijing's Central Academy of Drama. Zhang's first job was off screen as a "voice artist" dubbing films. TV roles and bit parts in films followed before Assembly director Feng Xiaogang gave him his breakthrough role. Most recently Zhang again donned a uniform for writer-director Yang Shupeng's take on the Sino-Japanese war, The Cold Flame (see The Film Director, below).

The actress

Fan Bingbing

It has been eight years since the runaway success of the Oscar-winning Ang Lee martial-arts epic Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon launched the international career of Zhang Ziyi. The Beijing-born beauty went on to appear in Rush Hour 2, House of Flying Daggers and Memoirs of a Geisha but as she approaches 30, a new generation of Chinese actresses is knocking at the door of Hollywood (where there rarely seems to be room for more than one Chinese star: Zhang was herself tagged the "new" Gong Li).

At the front of the queue is the doll-like model-turned-actress Fan Bingbing, 26, whose starring role in the controversial Lost in Beijing has launched a glittering career. The tale of prostitution, blackmail and rape, in which Fan plays a foot masseuse, has been banned by Chinese sensors and even caused a stir at last year's Berlin Film Festival.

The photographer

Wing Shya

For the first 30 years of the People's Republic, photography was reduced to a propaganda tool and it is only recently that photographers have truly broken the strictures of the state. In 2005, London's Victoria & Albert Museum hosted the first comprehensive survey of modern Chinese photography for a decade and the city of Guangzhou hosted China's first international photo biennale. The Hong Kong-based Wing Shya, 43, is perhaps the photographer with the greatest exposure in the West. He moved to Canada in his early twenties to study graphic design and worked briefly in advertising in New York, before heading home to set up his own studio, Shya La La. His heavily stylised and often edgy work has since appeared in i-D magazine, French Vogue and Time Style and Design, and he's a veteran of album cover designs. Meanwhile, brands including Louis Vuitton, Nike and Lacoste have signed him for high-profile campaigns. Wing's work is now on show at the V&A's China Design Now show, where his evocative "Pearls of the Orient" series features couture-clad models in a mocked-up Shanghai, circa 1930. But he is perhaps best known in the West for his collaboration with the Hong Kong film director Wong Kar Wai, for whom he served as graphic designer and photographer on the acclaimed films In the Mood for Love and 2046.

The author

Fan Wu

China's turbulent course through the 20th century gave rise to a stable of talented authors, whose searing novels documented a time of unimaginable upheaval. Millions of us wept through Wild Swans, Jung Chang's epic biographic tale of three women's struggle to endure life before, during and after Mao's revolution, which is due a much-anticipated film release next year. Sixteen years on, it's no surprise China's more recent modern history, of unprecedented economic growth and social change, has inspired a new school of writers. Fan Wu's debut novel, February Flowers, which was chosen as the inaugural book for the publisher Picador's Asia arm, has been a critical hit since its release last year. The Independent called the story of a society torn between tradition and modernity, dogma and freedom, as seen through the eyes of two young Chinese, "perfectly poignant", while its frank depiction of sexual awakening was seen as an antidote to the provocative work of another up-and-coming author, Wei Hui, whose novel Shanghai Baby was banned in China in 2000 for its overt hedonistic content. Fan grew up on a state-run farm in southern China and graduated from university in Nanjing in the mid-1990s. A Stanford scholarship brought her to the US, where she now lives and writes in California.

The rapper

Li Junju

Think Chinese music and the strained sounds of the Erhu probably spring to mind. But China has more to offer by way of music than the two-stringed instrument so beloved of film and documentary makers (as a cinematic signpost it has become almost as patronising as the red London bus). The Chinese pop-music industry is exploding and, while much of its output is derivative and insipid, there is room for trailblazers. Few artists can claim to be as original as Li Junju, aka Kirby Li, aka Sketch Krime, aka Verbal Confucius. His group, the Dragon Tongue Squad, is building a loyal fan base with its "hip-hop with Chinese characteristics". Kirby and his crew might have cut their teeth on the east coast (of China) but gangsta rap this is not. Heavy censorship means that, while the Squad might like to rap about shooting, pimping and sex, it must make do with trainers, clothes and romance. Kirby, however, occasionally employs verbal gymnastics to evade the censors. In one famous case, two subtle changes of tone (but not of words) turned the delightful "When I fucked the first hole" into the somewhat safer "When I floated the first season". It fooled the censors but not Dragon fans.

Earlier this year, Kirby's squad became the first Chinese hip-hop act to perform overseas when they appeared at the Royal Opera House as part of the China Now festival.

The film director

Yang Shupeng

Chinese directors have often struggled to break into Western cinema. Zhang Yimou, who was the brightest star in the so-called class of 1982 (the year he and fellow directors Chen Kaige and Tian Zhuangzhuang graduated from the Beijing Film Academy), has been easily the most successful, with a string of acclaimed art-house features including Raise the Red Lantern and The Road Home (in which Zhang Ziyi made her film debut). But despite minor success for more recent releases such as Zhang Yang's Spicy Love Soup and Shower, Western audiences seem to have developed an exclusive taste for sweeping, big-budget martial-arts epics such as Zhang Yimou's House of Flying Daggers and Hero, which followed Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

Yang Shupeng (aka Leon Yang) represents a new breed of directors hoping to re-crack the international market for Chinese drama. A former fireman, Yang's quick-cut, handheld camerawork is free of film-school tics and helped to turn his debut feature, The Cold Flame (Fenghuo), into a box-office hit when it was released on the mainland earlier this month. Set during the latter stages of the Sino-Japanese war, in the early 1940s, it focuses on the children left behind. Yang, 37, deftly avoids making political points as tensions between China and Japan simmer on, more than 60 years after the ceasefire.

The fashion designer

Han Feng

Most of what we wear is made in China but few of us associate the "world's factory" with haute couture. There are, however, designers who set their sights higher than mass-produced T-shirts and polyester pants. The UK-based Hong Kong designer Sir David Tang (see page 55) has turned his Shanghai Tang label into a global luxury brand (although it is now controlled by the Swiss firm Richemont) while Vivienne Tam, author of the glorious coffee-table book China Chic, has dressed the likes of Julia Roberts and Madonna. One designer hoping to follow in their footsteps is Han Feng, who has quietly been designing high-end collections for more than 10 years. In a vote of confidence in China's burgeoning fashion industry – Vogue launched a China edition in 2005 – Tam recently returned to her homeland, setting up shop in Shanghai after years in New York. Her clientele has grown steadily and, in 2005, she gained international prominence when she designed the extravagant costumes for the acclaimed production of Madame Butterfly directed by the late Anthony Minghella. Meanwhile, on the backstreets of China's increasingly cosmopolitan cities, there is a growing demand for ironic T-shirts and other garments inspired by retro-Communist imagery. In Shanghai, Shirtflag, founded by an avant-garde designer called Ji Ji, produces handbags and hoodies adorned with pictures of workers and farmers, as well as the kind of Mao icons more often found on tacky tourist trinkets.

The architect

Zhu Pei

China is perhaps second only to Dubai as a playground for architects keen to push the boundaries of engineering and, in some cases, taste. The country's booming cities are home to some of the most exciting works of modern building design, including Shanghai's Jin Mao tower, the tallest building on the mainland, the "bird's nest" Olympic stadium in Beijing, and the aquatics centre, which has been compared to an ice cube. But what all three structures have in common is that none started life on a Chinese drawing board. Their wings for so long clipped by state-run practices committed to throwing up soulless post-modern apartment blocks, Chinese architects have only recently begun to fly with their Western counterparts. Soaring highest is the Beijing-based Zhu Pei, who set up his own studio in 2005. Trained at Tsinghua University and the University of California, Zhu is the man behind Digital Beijing, the striking and imposing concrete control centre for the Olympics, which is designed to resemble an integrated circuit board. Other prestige projects include an origami-like art pavilion in Abu Dhabi that will stand alongside monuments by Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry, and designs for a riverside building made to look like a giant pebble that will house the work of the Chinese artist Yue Minjun (see below). Yet Zhu is happiest working on projects designed to reinvigorate Beijing's threatened hutongs, the capital's tangled network of residential alleyways and courtyards.

The artist

Yue Minjun

Trade in Chinese contemporary painting is booming. The art world gasped in 2006 when a painting by the painter Zhang Xiaogang sold for more than a million dollars at Sotheby's. And that was just the start; in the same year, Charles Saatchi paid £770,000 for another of Zhang's depictions of the Cultural Revolution, and the records kept falling. But it is the work of the renowned artist Yue Minjun that is collecting the highest bids. Last October, his masterpiece, The Execution, which was inspired by the bloody crackdown at Tiananmen Square in 1989, sold for a record £2.15m at an auction at Sotheby's in London. Painted in a month in 1995, the giant work shows a group of soldiers firing on four men, who are wearing only pants. The men also sport incongruous, manic grins, a feature that has become Yue's trademark since he started painting in the 1980s after working briefly on the oil fields of his native north-east China. Yue has been widely tagged as a "Cynical Realist", a term coined by the leading Chinese art critic Li Xianting to describe the country's post-Tiananmen generation of disillusioned artists. He sold Execution soon after he completed it to a Hong Kong art dealer for just US$5,000.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments