The beckoning silence: Why half of the world's languages are in serious danger of dying out

Of the 6,500 languages spoken in the world, half are expected to die out by the end of this century. Now, one man is trying to keep those voices alive by reigniting local pride in heritage and identity.

High up, perched among the remote hilltops of eastern Nepal, sits a shaman, resting on his haunches in long grass. He is dressed simply, in a dark waistcoat and traditional kurta tunic with a Nepalese cap sitting snugly on his head. To his left and right, two men hold recording devices several feet from his face, listening patiently to his precious words. His tongue elicits sounds alien to all but a few people in the world, unfamiliar even to those who inhabit his country. His eyes flicker with all the intensity of a man reciting for the first time to a western audience his tribe's version of the Book of Genesis, its myth of origins.

The shaman's story is centuries old, passed down from one generation to the next through chants, poems, songs, proverbs and plain story-telling. Yet this narrative and, indeed, his entire language have never been recorded in text. And, faced with the onslaught of rapid globalisation and social change, they are dying. Whether it be through well-intentioned national education programmes in Nepalese, the younger generation leaving for bigger Asian cities or simply the death of elders, the day when no one will speak the ancient tongue of the Rai tribe is fast approaching.

The plight of the shaman's language and that of his community is by no means confined to this small, but beautiful area of Nepal; it is the apparent fate of thousands of ' communities, societies and indigenous groups all around the world. But not if Dr Mark Turin can help it.

The University of Cambridge academic is leading a project that aims to pull thousands of languages back from the brink of extinction by recording and archiving words, poems, chants – anything that can be committed to tape – in a bid to halt their destruction. Languages the majority of us will never know anything about.

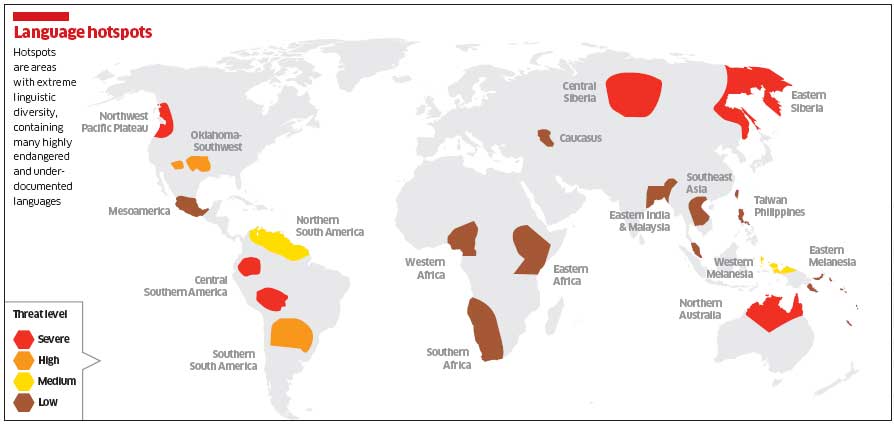

Of the world's 6,500 living languages, around half are expected to die out by the end of this century, according to Unesco. Just 11 are spoken by more than half the earth's population, so it is little wonder that those used by only a few are being left behind as we become a more homogenous, global society. In short, 95 per cent of the world's languages are spoken by only five per cent of its population – a remarkable level of linguistic diversity stored in tiny pockets of speakers around the world.

In a small office room in the back of Cambridge's Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology – a place in which you almost expect Harrison Ford to walk around the corner at any moment, fedora on head, whip in hand – Turin looks over the contents of a box that arrived earlier in the morning from India. "[The receptionists] are quite used to getting these boxes now," says the 36-year-old anthropologist, who is based at the university. Inside the box, which is covered in dozens of rupee postage stamps, are DVDs representing hours of chants, songs, poems and literature from a tiny Indian community that is desperate for its language to have a voice and be included in Turin's venture.

For many of these communities, the oral tradition is at the heart of their culture. The stories they tell are creative works as well as communicative. Unlike the languages with celebrated written traditions, such as Sanskrit, Hebrew and Ancient Greek, few indigenous communities – from the Kallawaya tribe in Bolivia and the Maka in Paraguay to the Siberian language of Chulym, to India's Arunachal Pradesh state Aka group and the Australian Aboriginal Amurdag community – have recorded their own languages or ever had them recorded. Until now. Turin launched the World Oral Literature Project earlier this year with an aim to document and make accessible endangered languages before they disappear without trace.

He is trying to encourage indigenous communities to collaborate with anthropologists around the world to record what he calls "oral literature" through video cameras, voice recorders and other multimedia tools by awarding grants from a £30,000 pot that the project has secured this year. The idea is to collate this literature in a digital archive that can be accessed on demand and will make the nuts and bolts of lost cultures readily available. As useful as this archive will be for Western academic study – the World Oral Literature Project is convening for its first international workshop in Cambridge this week – Turin believes it is of vital importance that the scheme also be used by the communities he and his researchers are working with.

The project suggested itself when Turin was teaching in Nepal. He wanted to study for a PhD in endangered languages and, while discussing it with his professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, was drawn to a map on his tutor's wall. The map was full of pins of a variety of colours which represented all the world's languages that were completely undocumented. At random, Turin chose a "pin" to document. It happened to belong to the Thangmi tribe, an indigenous community in the hills east of Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. "Many of the choices anthropologists and linguists who work on these traditional field-work projects take are quite random," he admits. "There's a lot of serendipity involved."

Continuing his work with the Thangmi community in the 1990s, Turin began to record the language he was hearing, realising that not only was this language and its culture entirely undocumented, it was known to few outside the tiny community. He set about trying to record their language and myth of origins (see box, page 17). "I wrote 1,000 pages of grammar in English that nobody could use – but I realised that wasn't enough. It wasn't enough for me, it wasn't enough for them. It simply wasn't going to work as something for the community. So then I produced this trilingual word list in Thangmi, Nepali and English."

In short, it was the first ever publication of that language. That small dictionary is still sold in local schools for a modest 20 rupees, and used as part of a wider cultural regeneration process to educate children about their heritage ' and language. The task is no small undertaking: Nepal itself is a country of massive ethnic and linguistic diversity, home to 100 languages from four different language families. What's more, ever fewer ethnic Thangmi speak the Thangmi language. Many of the community members have taken to speaking Nepali, the national language taught in schools and spread through the media, and community elders are dying without passing on their knowledge.

Since the project got under way, along with similar ventures by the National Geographic initiative Enduring Voices, the Hans Rausing Endangered Languages Project and the Arcadia Fund, many more communities around the world have similarly either requested inclusion or responded to the suggestion that their language is in need of recording. (One task involved making recordings of ceremonial chants of the Barasana language, spoken by just 1,890 people in the Vaupés region of Columbia.)

The lexicographer Dr Sarah Ogilvie worked with the Umagico Aboriginal community at Cape York Peninsula in northern Australia, for example. Like Turin, she developed an entire dictionary of the community's language, Morrobalama – the first time their purely oral language had ever been written and recorded. Living with the community for a year-and-a-half in difficult conditions and being the only non-native person in the group, she began learning the language from scratch, as no one spoke English.

"As a lexicographer, I wanted to look at how we could write better dictionaries of languages that are dying – that not only preserve the language, but can be used as practical tools themselves," says Ogilvie.

After learning Morrobalama orally, she started her dictionary by writing the words down in the International Phonetic Alphabet. Then, by looking for patterns in the sounds, she was able to come up with a unique writing system. "I was lucky in the sense that no one else had tried to record the language before; often for linguists, the situation is made more complex if someone has already attempted to record the language before them – it may have been written badly, yet you can't erase it and the community might have actually become quite attached to it."

Despite Turin's enthusiasm for his subject, he is baffled by many linguists' refusal to engage in the issue he is working on. "Of the 6,500 languages spoken on Earth, many do not have written traditions and many of these spoken forms are endangered," he says. "There are more linguists in universities around the world than there are spoken languages – but most of them aren't working on this issue. To me it's amazing that in this day and age, we still have an entirely incomplete image of the world's linguistic diversity. People do PhDs on the apostrophe in French, yet we still don't know how many languages are spoken.

"When a language becomes endangered, so too does a cultural world view. We want to engage with indigenous people to document their myths and folklore, which can be harder to find funding for if you are based outside Western universities. If you are a Himalayan tribesman, you might not have access to a video camera to record your shaman and elders."

While these languages may seem remote and distant, it is worth remembering that British languages such as Welsh and Gaelic were in danger of becoming extinct not so long ' ago. In fact, Turin admits that these languages, too, including Cornish, need considerable effort to keep them going. "People often think it's only tribal cultures that are under threat. But all over Europe there are pockets of traditional communities and speech forms that have become extinct. It is the domain of stronger nation states with better resources to look after their own indigenous tongues, through Welsh-language TV, for example, and for those from north-western France, Breton literature."

Similar to the introduction of the Welsh Language Act in 1993, the Scottish Government is moving to protect and promote Gaelic. A new agreement means that Gaelic can now be used formally in meetings between Scottish government ministers and EU officials. An extra £800,000 was also pledged for a project promoting Gaelic in schools, taking the level of funding to £2.15m. Nevertheless, Scottish Gaelic is not one of the EU's list of 23 "official" languages.

Yet, despite the struggles facing initiatives such as the World Oral Literature Project, there are historical examples that point to the possibility that language restoration is no mere academic pipe dream. The revival of a modern form of Hebrew in the 19th century is often cited as one of the best proofs that languages long dead, belonging to small communities, can be resurrected and embraced by a large number of people. By the 20th century, Hebrew was well on its way to becoming the main language of the Jewish population of both Ottoman and British Palestine. It is now spoken by more than seven million people in Israel.

Turin's projects receive a tiny fraction of the amounts spent in the UK on promoting language, but he believes there is much more at stake than even language and culture in the communities he works with: their extinction hints at dangers for the very biodiversity of their homelands, too. Experts now agree that there is a correlation between areas of cultural, linguistic and biological diversity. The mountain ranges, rivers and gorges that might isolate a human community and lead to the development of their specific native tongue are often the same geographical features that give rise to specialised ecosystems.

"The more flora and fauna you have, the more you can eat, therefore the less people have to trade, minimising the effects of interaction with other outside influences," he says. "In parts of Papua New Guinea, for example, five minutes away from your house you have everything you need to survive. Places that are diverse in species are diverse in languages and cultures." In other words, if the locals start speaking other languages, it is indicative of a growing outside influence – and that can be bad news for the ecology.

Yet, despite the difficulties these communities face in saving their languages, Dr Turin believes that the fate of the world's endangered languages is not sealed, and globalisation is not necessarily the nefarious perpetrator of evil it is often presented to be. "I call it the globalisation paradox: on the one hand globalisation and rapid socio-economic change are the things that are eroding and challenging diversity. But on the other, globalisation is providing us with new and very exciting tools and facilities to get to places to document those things that globalisation is eroding. Also, the communities at the coal-face of change are excited by what globalisation has to offer."

In the meantime, the race is on to collect and protect as many of the languages as possible, so that the Rai Shaman in eastern Nepal and those in the generations that follow him, can continue their traditions and have a sense of identity. And it certainly is a race: Turin knows his project's limits and believes it inevitable that a large number of those languages will disappear. "We have to be wholly realistic. A project like ours is in no position, and was not designed, to keep languages alive. The only people who can help languages survive are the people in those communities themselves. They need to be reminded that it's good to speak their own language and I think we can help them do that – becoming modern doesn't mean you have to lose your language."

Vanishing Voices: Dr Mark Turin discusses endangered languages

To see and hear recordings of the Thangmi in Nepal: www.digitalhimalaya.com/collections/thangmiarchive/thangmifilm.php. For more on National Geographic's Enduring Voices project: nationalgeographic.com/mission/enduringvoices. For more information visit the Hans Rausing Endangered Languages Project, www.hrelp.org and the World Oral Literature Project, www.oralliterature.org

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks