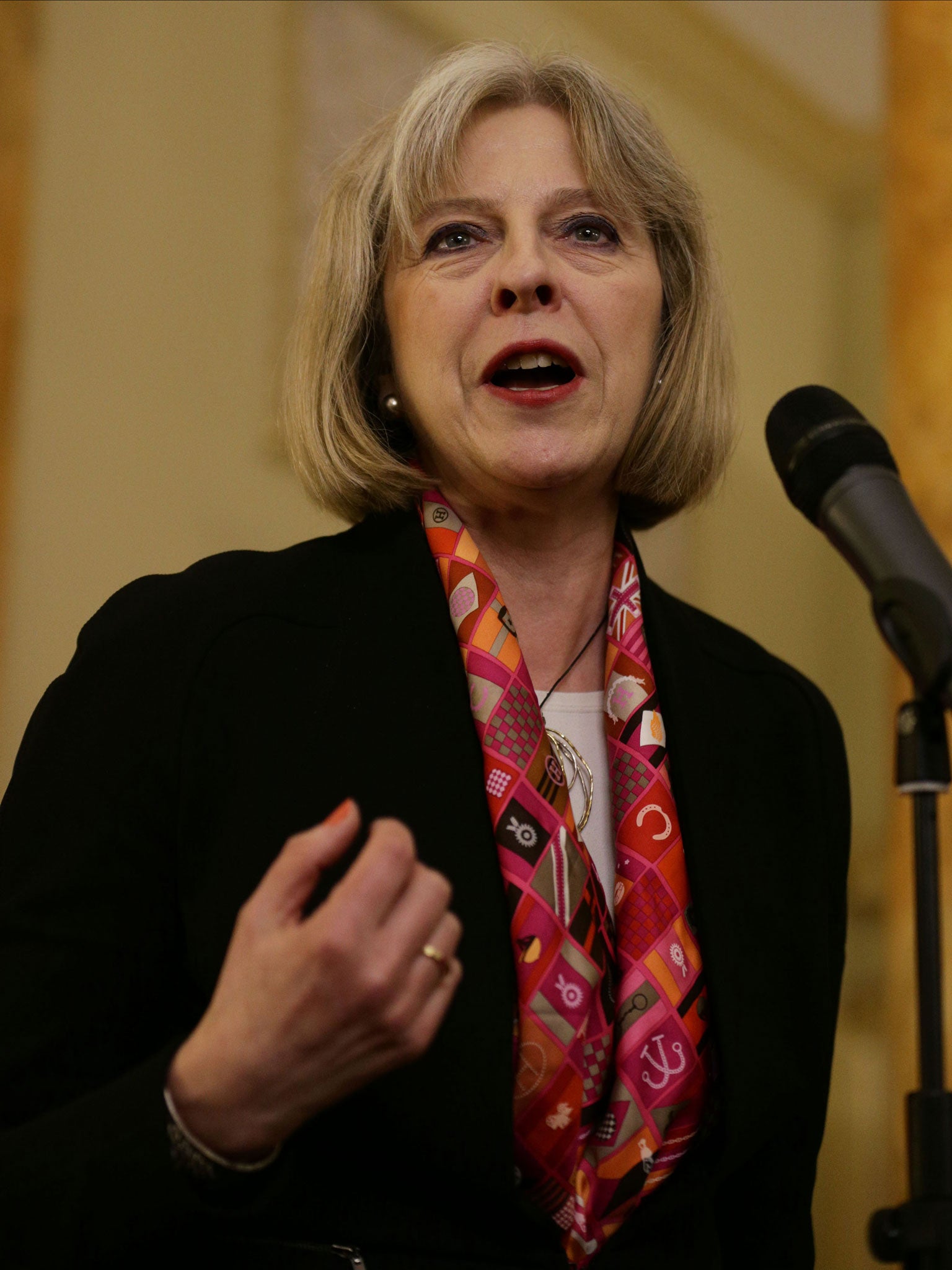

Stranded in Pakistan – after Theresa May revoked his passport

A Home Office crackdown has seen 27 Britons lose their citizenship since 2006. One victim of the purge talks to Patrick Galey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When a British man took a holiday to visit relatives in Pakistan in January 2012, he had every reason to look forward to returning home. He was working full-time at the mobile-phone shop beneath his flat in south-east London, had a busy social life and preparations for his family’s visit to the UK were well under way.

Two years later, the man, who cannot be named for legal reasons, is stranded in Pakistan. He claims he is under threat from the Taliban and unable to find work to support his wife and three children. He is one of 27 people who have lost their British citizenship since 2006 on the orders of the Government, on the grounds that their presence is “not conducive to the public good”.

The process has been compared to “medieval exile” by the leading human-rights lawyer Gareth Peirce. Today, the House of Lords will debate a clause contained within the Immigration Bill to expand the draconian powers. The proposal was added with little warning and was overwhelmingly voted through by MPs, but confusion has since emerged about how the law might function in practice.

The man, who can only be referred to as E2 for legal reasons, is the first to speak out about his ordeal. He told the Bureau of Investigative Journalism: “My British citizenship was everything to me. I could travel around the world freely. That was my identity but now I am nobody.”

The man was born in Afghanistan and still holds Afghan citizenship. He claimed asylum in Britain in 1999 after fleeing the Taliban regime in Kabul, and was granted indefinite leave to remain. In 2009 he became a British citizen. While his immediate family remained in Pakistan, he came to London, where he worked and integrated in the local community.

Although the interview was conducted in his native Pashto, E2 can speak some English. “I worked and I learned English,” he says. “Even now I see myself as a British. If anyone asks me, I tell them that I am British.”

But as of 28 March 2012, E2 is no longer a British citizen. After he boarded a flight to Kabul in January 2012 to visit relatives in Afghanistan and his wife and children in Pakistan, a letter signed by the Home Secretary, Theresa May, was sent to his London address from the UK Border Agency, saying he had been deprived of his British nationality.

In evidence that remains secret even from him, E2 was accused of involvement in “Islamist extremism” and deemed a national security threat. He denies the allegation and says he has never participated in extremist activity.

In the letter, Ms May wrote: “My decision has been taken in part-reliance on information which, in my opinion, should not be made public in the interest of national security and because disclosure would be contrary to the public interest.” E2 claims he had no way of knowing his citizenship had been removed and that the first he heard of the decision was when he was met by a British embassy official at Dubai airport on 25 May 2012, when he was on his way back to the UK and well after his appeal window shut.

E2’s lawyer appealed anyway, launching proceedings at the Special Immigration Appeals Commission (Siac), a tribunal that can hear secret evidence in national security-related cases. He said: “Save for written correspondence to the appellant’s last-known address in the UK expressly stating that he has 28 days to appeal, ie acknowledging that he was not in the UK, no steps were taken to contact the appellant by email, telephone or in person until an official from the British Embassy met him at Dubai airport and took his passport from him.”

The submission noted: “It is clear from this [decision] that the [Home Secretary] knew that the appellant [E2] is out of the country as the deadline referred to is 28 days.”

The Home Office disputed that E2 was unaware of the order against him and a judge ruled that he was satisfied “on the balance of probabilities” that E2 did know about the removal of his citizenship. “[W]e do not believe his statement,” the judge added.

E2 says his British passport was confiscated and, after spending 18 hours in an airport cell, he was made to board a flight back to Kabul and has remained in Afghanistan and Pakistan ever since. He is now living on the border of Waziristan, from where he agreed to speak to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism last month.

While rules governing hearings at Siac mean some evidence against E2 cannot be disclosed on grounds of national security, the bureau has been able to corroborate key aspects of E2’s version of events, including his best guess as to why his citizenship was stripped. His story revolves around an incident that occurred thousands of miles away from his London home and several years before he saw it for the last time. In November 2008, the Afghan national Zia al-Haq al-Ahady was kidnapped as he left the home of his infirm mother in Peshawar, Pakistan. The event might have gone unnoticed were he not the brother of Afghanistan’s then Finance Minister and former presidential hopeful Anwar al-Haq al-Ahady, who intervened, and after 13 months of tortuous negotiations with the kidnappers, a ransom was paid and Mr Ahady was released. E2 claims to have been the man who drove a key negotiator to Mr Ahady’s kidnappers.

E2 guesses – since not even his lawyers have seen the specific evidence against him – that it was this activity that brought him to the attention of British intelligence services. After this point, he claims he was repeatedly stopped as he travelled to and from London and Afghanistan and Pakistan to visit relatives.

“MI5 questioned me for three or four hours each time I came to London at Heathrow airport,” he says. “They said people like me [Pashtun Afghans] go to Waziristan and from there you start fighting with British and US soldiers. The very last time [I was questioned] was years after the [kidnapping]. I was asked to a Metropolitan Police station in London. They showed me pictures of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar [the former Afghan Prime Minister and militant with links to the Pakistani Taliban (TTP)] along with other leaders and Taliban commanders. They said: ‘You know these guys’.”

He claims he was shown a photo of his wife – a highly intrusive action in conservative Pashtun culture – as well as one of someone he was told was Sirajuddin Haqqani, commander of the Haqqani Network, one of the most lethal TTP-allied groups.

“They said I met him, that I was talking to him and I have connections with him. I said: ‘That’s wrong’. I told [my interrogator] that you can call [Anwar al-Ahady] and he will explain that he sent me to Waziristan and that I found and released his brother. I don’t know Sirajuddin Haqqani and I didn’t meet him.”

A spokesman for the Home Office said: “The Home Secretary will remove British citizenship from individuals where she feels it is conducive to the public good to do so.” When challenged specifically on allegations made by E2, he said the Home Office did not comment on individual cases.

E2 says he now lives in fear for his safety in Pakistan. Since word has spread that he lost his UK nationality, locals assume he is guilty, which he says puts him at risk of attack from the Pakistani security forces. He also says his family has received threats from the Taliban for his interaction with MI5.

“People back in Afghanistan know that my British passport was revoked because I was accused of working with the Taliban. I can’t visit my relatives and I am an easy target to others,” he says. “Without the British passport here, whether [by] the government or Taliban, we can be executed easily.”

E2 is not alone in fearing for his life after being exiled from Britain. Two British nationals stripped of their citizenship in 2010 were killed a year later by a US drone strike in Somalia. A third Briton, Mahdi Hashi, disappeared from east Africa after having his citizenship revoked in June 2012 only to appear in a US court after being rendered from Djibouti. E2 says if the British Government is so certain of his involvement in extremism they should allow him to stand trial in a criminal court.

“When somebody’s citizenship is revoked if he is criminal he should be put in jail, otherwise he should be free and should have his passport returned,” he says.

“My message [to Theresa May] is that my citizenship was revoked illegally. It’s wrong that only by sending a letter that your citizenship is revoked. What kind of democracy is that?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments