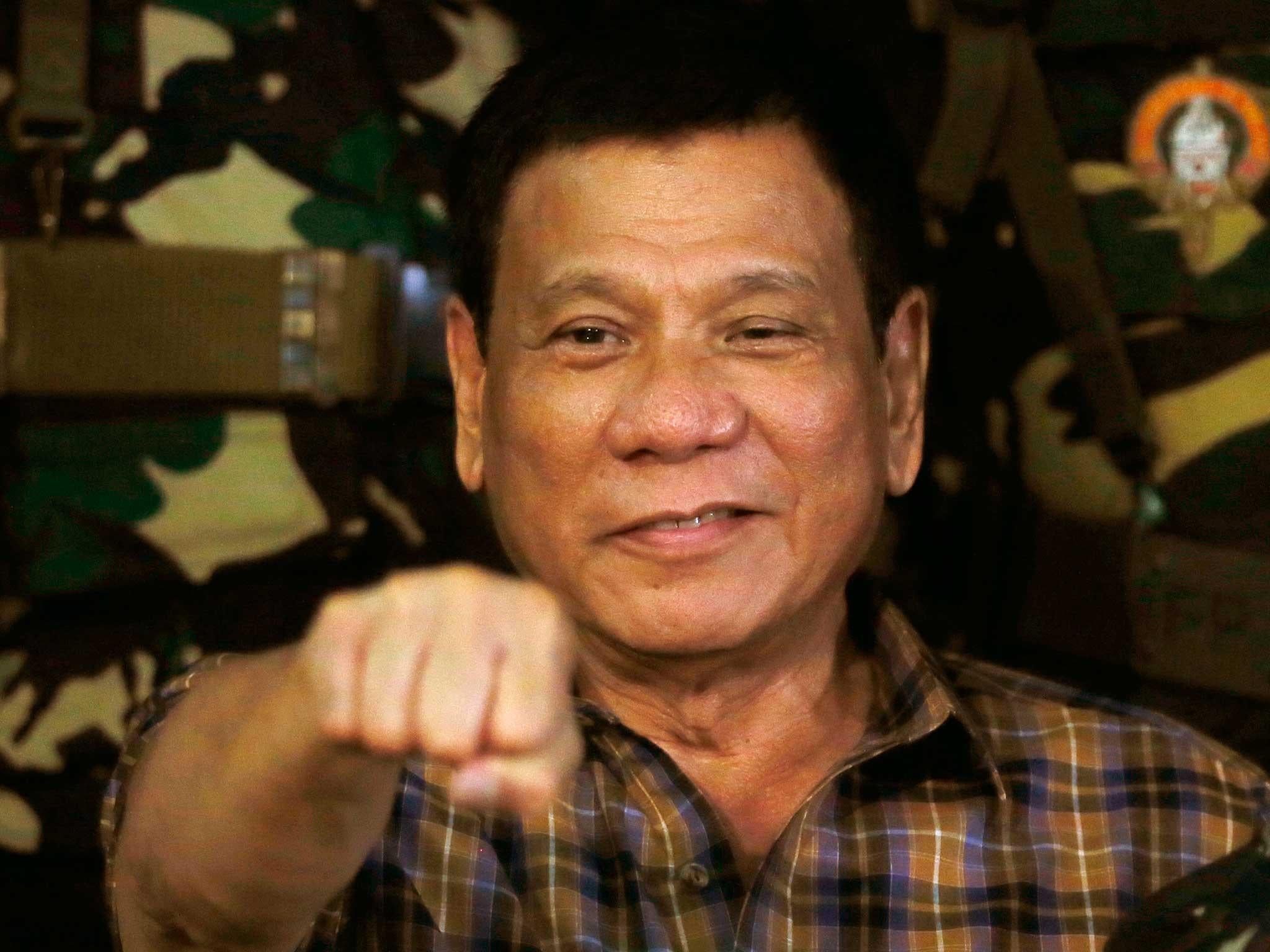

Welcome to ‘Duterte city’, where the Philippines president used to be ‘the death squad mayor’

On the island of Mindanao’s southeast coast, the cult of Duterte is strong. A curfew keeps unaccompanied minors off the streets after 10pm, the sale of liquor after 2am is prohibited, and, as one unlucky tourist learned, you can only smoke in designated places – or else...

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.People here love to tell stories about the man they call “our mayor”.

One time, when a tourist ignored no smoking rules, our mayor stormed a restaurant with a revolver and forced him to eat the butt. Our mayor patrolled the streets on his motorcycle. Our mayor saved us from thugs.

The mayor they speak of is Rodrigo Duterte, who ran this coastal city on the island of Mindanao, in the southern Philippines, for more than two decades before being elected president this spring.

Since taking power in Manila, Duterte has made international headlines for all the wrong reasons. His call to “kill all” the country’s criminals has unleashed an extraordinary wave of violence, with police shooting dead more than a thousand suspects, and plainclothes assassins dumping an even greater number of bodies on the streets.

When President Barack Obama raised the issue, Duterte lectured him about US colonialism and used a slang term that translates, roughly, as “son of whore”. When the European Parliament issued a statement condemning deaths, Duterte said, “F*** you” – and gave them the finger for good measure.

His sharp tongue risks turning him into a pariah abroad, but only serves to help him at home. Despite the violent deaths of 3,000 Filipinos in less than three months, Duterte remains popular in the Philippines, with high approval ratings and strong legislative support.

As the political class falls in line, the cost of crossing him grows. When a longtime Duterte critic, Senator Leila de Lima, opened a senate investigation on extrajudicial killing, he publicly urged her to hang herself.

When she presented a witness who claimed he killed for Duterte in Davao, once feeding a man to a crocodile, she was ousted from her role as chair of the Senate Commission on Justice and Human Rights.

The senator has since been publicly accused of taking bribes from drug dealers and sleeping with her driver. Her personal number and address were broadcast on national television, leading to threats.

“She was not only screwing her driver, she was screwing the nation,” the president joked.

She’s not laughing. “The truth is, I’m not safe,” she said.

To understand how a man who makes crude jokes about women and urges troops to “massacre” suspects became the Philippines’s best hope, look to Davao.

In this coastal city on Mindanao’s southeast, the cult of Duterte is strong. The president’s daughter, Sara Duterte, was sworn in for her second term as mayor in July, the same day his son, Paolo Duterte, became vice-mayor. This, a sign reminds you, is “Duterte city”.

By the standard of Philippine metropolises, Davao is an orderly place. A curfew keeps unaccompanied minors off the streets after 10pm. The sale of liquor after 2am is prohibited. And, as that unlucky tourist learned, you can only smoke in designated places – or else.

Around town, banners remind people whom to thank for city rules: “President Duterte: Thank you for making Davao City smoke-free,” reads an apparent favourite.

The former mayor’s status as the local strongman is such that street vendors hawk novelty licence plates emblazoned with “Du30”. One shop was selling a red T-shirt, available in children’s size, that showed the president firing a gun.

Another popular piece of Duterte merchandise shows him riding a motorcycle, his fist raised in victory, with the tagline: “Change is coming”.

Several people here compared him to a strict parent – “a real disciplinarian,” one man said – and seemed to see him as their personal protector.

At the market, Mila Sultan, a vendor who lives and works in her stall, credited the former mayor with making the city livable.

“Even if you sleep on the sidewalk, nobody will harm you,” she said.

Abear P Bato, who runs two halal food stands, said Duterte supported small businesses and helped them thrive by keeping crime at bay. “He’s a great guy,” he said.

If Duterte doesn’t do those killings, there are a lot of victims, especially the young generation. Be a good person in Davao and the mayor will help you

And what of the Davao Death Squad, the contract killers that journalists and rights groups say Duterte backed? Or the senate witness who said Duterte ordered them to kill criminals and critics alike?

“No comment,” said Ms Sultan.

“I have no comment on that,” Mr Bato said. “He’s a good guy, but don’t break his rules.”

In most contexts, earning the nickname “the Death Squad mayor” would be a political disaster. To Duterte and his fans, it’s a source of pride.

Dogged by questions about extrajudicial killings in Davao, Duterte has not shied away from his bloody record. “Am I the death squad? True,” he said in May.

The fact is, millions of Filipino voters look at Davao’s transformation with envy – whatever it cost.

The city, like the Philippines as a whole, was mismanaged for centuries. It was occupied by the Spanish, seized by the United States, held by the Japanese – and plundered at every step.

When Duterte entered politics in the mid-1980s, the dictator Ferdinand Marcos was out, but no power had replaced him. Davao, nicknamed “Murder City,” was plagued by rival insurgencies and ceaseless crime.

The mayor set out to change that – by force. When Filipino journalist Sheila Coronel and a colleague toured Davao with the newly elected mayor in 1988, he bragged to them about pulling the plug on a still-alive drug kingpin and pushing a dealer out of a helicopter, she wrote in the Atlantic.

Stories by Filipino journalists and reports by rights groups point to a pattern of extrajudicial violence in Davao that is strikingly similar to what’s unfolding nationwide today.

During much of Duterte’s tenure as mayor, suspected criminals were summarily executed by police or gunned down by plainclothes assassins riding on motorcycles. Few cases were ever investigated.

To the families of the victims and critics of the president, that constitutes an appalling abuse of power. But to Filipinos fed up with a sclerotic justice system and exhausted by crime, Davao is proof that, with some bloodletting, things can change.

In Davao, those who dared speak about their former mayor insisted that, on his watch, only “bad guys” get hurt.

“If Duterte doesn’t do those killings, there are a lot of victims, especially the young generation,” said Chris Yaco, a rice vendor. “Be a good person in Davao and the mayor will help you.”

The whole nation is hoping against fear that he’s right.

“Rody Duterte,” reads a sign in Davao, “The People’s last hope.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments