A veiled message: Pakistan women to show country’s #MeToo movement is still alive

Women who have been sexually abused will hold huge veils aloft on International Women’s Day in several protests across Pakistan to draw attention to the abuse they have suffered, reports Alia Waheed

In a college playing field, a red gossamer veil with intricate gold embroidery has been carefully laid out on the grass. A young woman takes a paint brush hesitantly, then starts to daub it with paint.

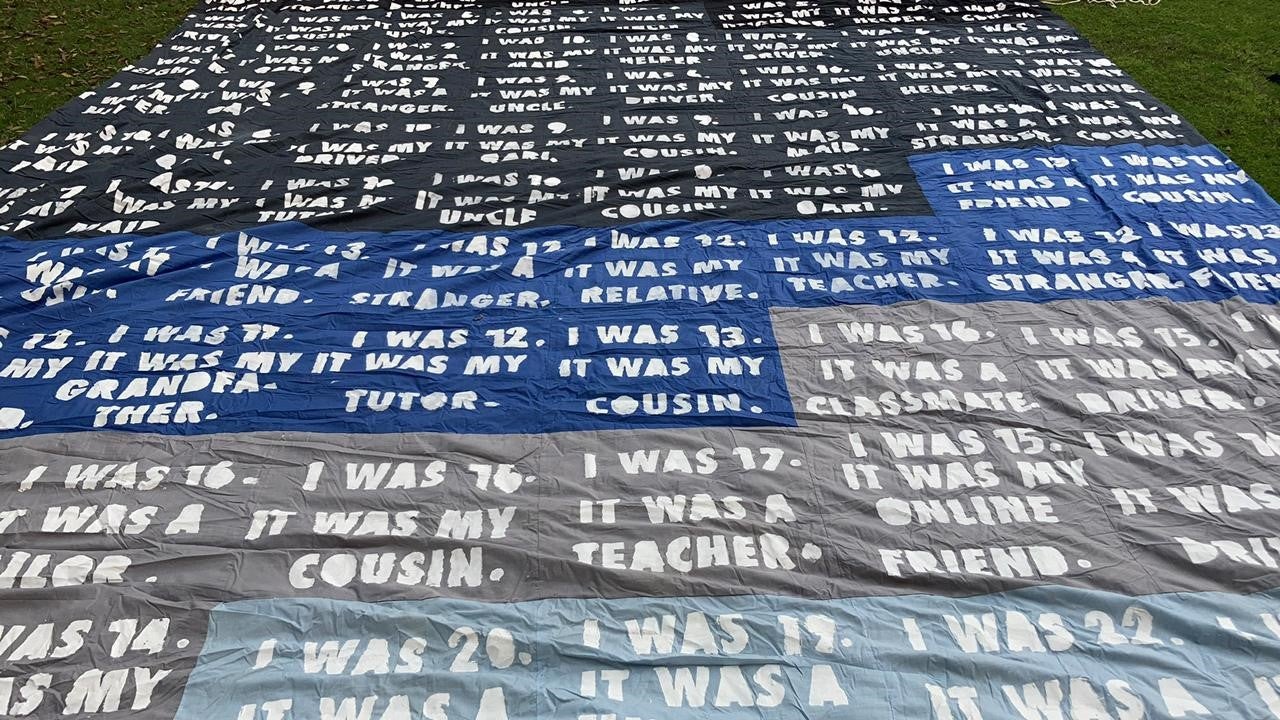

The bleak words she writes are at odds with the delicate fabrics in vibrant monsoon colours which gleam in the sun.

She is one of a group of students attending a workshop at a college in Lahore, Pakistan, for woman who have been sexually abused, in which they have been painting their #MeToo stories on to red veils.

They will be sewn together to make a huge veil which protestors will hold aloft during the Aurat March (Women’s March), which will take place across cities in Pakistan for International Women’s Day today (Monday, March 8).

The workshops were set up by Leena Ghani, organiser of the Lahore branch of the march who said she was overwhelmed by the response, as painted veils flooded in from across the country.

“The response was way bigger than I could imagine. It was sad that each one represented a woman’s trauma. It was very triggering for many women but also it’s a collective healing,” said Ghani, an artist and human rights activist.

“We built up a community by making our veils. It was a cathartic experience and many of the women felt it brought closure.”

The red veil, called a duppata, is a powerful symbol in Pakistani culture as they are traditionally worn by women on their wedding day and represent the bride’s sexual purity and honour on the biggest day of her life.

“Every day, people think #MeToo is dead in Pakistan and these duppatas are a visual representation that #MeToo is very much alive.

“People say the duppata is our protection, but the truth is, if a woman is raped, the first thing people ask is what was she wearing. Look at the words on the veil - that shows our bodies beneath the veil are being vandalised.”

For many of the women taking part in the workshops, it is the first time they have spoken about their experiences. Among them was Ayesha, 17. “I wrote about being raped by my grandfather.

“He tried to kiss me so many times. I would keep my lips in my mouth, he would suck them out so they bled. I felt so dirty after. I would spend hours in the shower trying to wash his touch off me. I kept everything bottled up and that trauma became my personality.”

“In our culture, elderly relatives should be honoured and never questioned. Women are always told to stay aware of the outside world. Nobody told me what to do when someone in your own home molests you. That’s why I painted my veil. Even though I can’t tell my family, I can speak out through my veil.”

For Shaista 19, painting her veil was particularly painful as after she gets home from the workshop, she will be going shopping for bridal clothes for the woman marrying her brother – the brother who molested her.

“I was 12 when my older brother first got into bed with me. When he lifted the covers, his voice and demeanour changed so it was like a stranger. I later discovered that he himself had been raped by some older boys at a madrassa (religious school) when he was six.

“It was difficult to process my feelings because in every other way, he was the perfect big brother. I felt sorry for what he went through, but also angry and hurt about what he did to me, yet I still loved him.

“He’s getting married in April and I have to act like the perfect groom’s sister, singing and dancing and smiling while knowing what he did.”

In its fourth year, the Aurat March started off as an informal gathering organised in a local park by women’s rights activists in the port city of Karachi, but has since evolved into a national movement as thousands of women from all backgrounds stand side by side to call for change.

Perhaps it was inevitable that any women led event which challenged the patriarchy would attract a backlash, but last year the level of vitriol took everyone by surprise as the slogan ‘Mere Jism, Meri Maarzi’ (my body, my choice) was seized upon by conservatives who accused the organisers of promoting prostitution and of being financed by the west to undermine the country’s Muslim values.

Ghani and the other organisers faced death threats and marchers were relentlessly harassed on social media and had their placards doctored and spread online.

However, as thousands of women take to the streets across Pakistan, for this year’s Aurat March, it shows that the battle for women’s rights shows no sign of being deterred.

And the women who have been silenced about their #MeToo experiences will finally find a voice, albeit, under the anonymity of red gossamer veil. “The veil will give me back some of my honour after all,” said Ayesha as she lay herduppata out to dry in the sun.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

1Comments