Nagasaki anniversary: How a Christian cathedral built following centuries of persecution was destroyed by the atomic bomb

After centuries of persecution, Christians were being allowed to worship, only to see their cathedral atomised

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 17 March 1865, a French missionary priest, Father Bernard Thadeo Petitjean, was kneeling to say his evening prayers in the Oura Catholic church, which stands on a hill overlooking the harbour of Nagasaki, and was the first Christian church allowed in Japan in modern times.

St Francis Xavier had begun his mission to Japan in 1549; Christianity was prohibited in 1614; the last priest was killed in 1644. All missionaries were either killed or expelled. All native priests had been executed, and thousands of Christians done to death, by burning, crucifixion, bombardment by Dutch gunners (the Dutch were not regarded by the Japanese as Christians), and various other modes of torture. Not a vestige of the religion – which at its height had claimed two hundred thousand adherents in Nagasaki alone – remained.

As Father Petitjean prayed, he became aware of around a dozen Japanese standing at the back of the church, staring curiously. Father Petitjean went and introduced himself to them. Speaking in Japanese, he said: “I am a Christian Father.”

A woman asked him: “Do you obey the Father in Roma?” “Yes.” “Do your priests marry?” “No.” “Do you observe the Sad Season and the Rising from the Dead?” “Yes.” Then: “Where is Maria?” In growing astonishment, Father Petitjean took the group to a statue of the Virgin and Child, which still stands to the right of the High Altar. The Japanese were evidently much moved, and the woman put her hand on her breast and said: “We are all of the same heart as you.”

This was the first evidence of what no one in the West had suspected, and would certainly have found incredible – the existence of “hidden Christians” in Japan, who, for nearly 250 years, without priests, prayer-books or scripture, and in total secrecy and silence, had preserved some memory and practice of the faith. These people had walked into Nagasaki from a village a few miles away.

The Japanese shoguns had become convinced that Christianity was part of a plot by the Spanish and Portuguese to conquer Japan. They tried to extirpate the faith which have hardly any historical parallel, except perhaps the persecution of the Cathars by the Catholic Church.

The chief method of getting people to prove they were not Christians – or to renounce their faith – was the famous “treading of the fumie”. The fumie were bronze (usually) representations of Christ or the Virgin, set into a wooden board. You were required to trample on these images.

Since Nagasaki had been the greatest Christian centre, all the inhabitants of that part of Japan were required to tread the fumie. Once a year, with great ceremony and special music, the images were brought from the Magistrate’s house, and taken to all the houses in the district. The sick were compelled to do the treading in bed.

Memories of Christianity survived only in a few villages. Without scriptures or prayer-books – and being, anyway, illiterate peasants and fishermen – the hidden Christians had only a few symbols. A family might have a kannon – a Buddhist goddess of mercy – standing in the kitchen. She would often be holding a child, or have children holding her skirts (you can see these in the little museum in a village near Nagasaki). Sometimes there was a small cross engraved on the back. Of course this kannon was the Virgin and Child.

Over more than two centuries, the religious practices of these peasants mixed with Shinto and Buddhism. They worshipped Buddhist demi-gods, but especially an important spirit by the name of “Deus”. They sang what they called an orasho – which must be from the Latin oratio – in a sort of plainsong. Acting on the instructions of the last priests, before they were killed, they appointed men to special offices: to memorise the Feasts, to baptise with water from an island spring, to memorise Latin prayers.

When the Meiji Restoration of 1868 brought religious freedom to Japan, about 15,000 Hidden Christians emerged. Around half of them rallied to the Church; the rest preferred to cleave to the practices of their ancestors, the origins of which they have forgotten. These include a special meal where they sit at low tables, ceremoniously eating raw fish and drinking sake and bowing continually to each other. This was the closest they could come to celebrating the Mass.

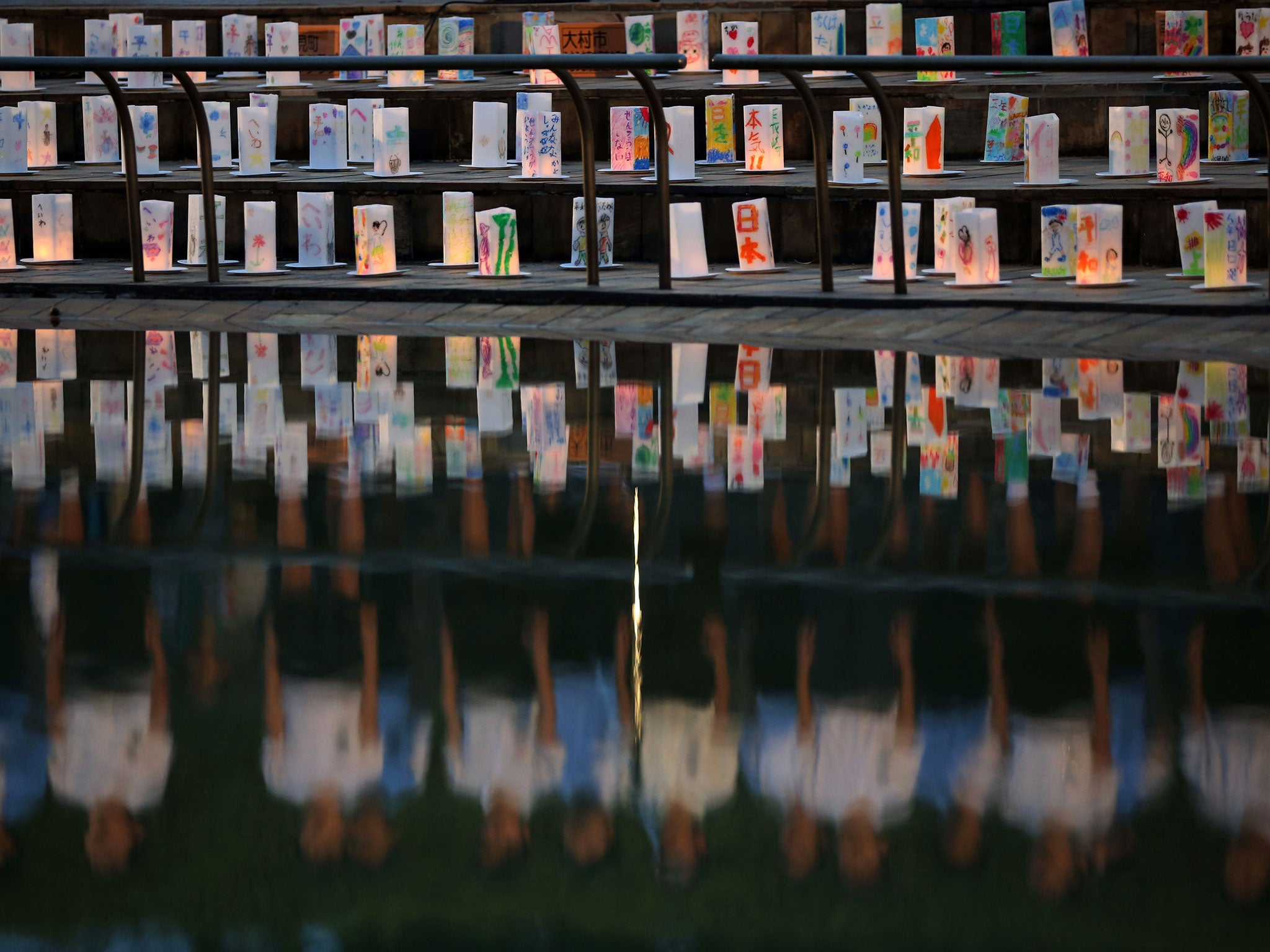

The memory of the persecuted Christians seems to have caught the imagination of modern Japanese. In the centre of Nagasaki there is a memorial to 26 martyrs who were eventually canonised – all looking improbably serene as they are crucified. There is also a memorial, of unexampled hideousness, called “The Secret Christian Spring”, with a waterfall that symbolises “the suffering and salvation of the Secret Christians”. The rough porcelain tiles on the lower part of the altar are meant to suggest “the harshness of lives of the Christians living underground”.

Christianity flourished again in Nagasaki. After 32 years, a huge Gothic cathedral – the largest in the Far East – was consecrated in 1914. That building ceased to exist at on 9 August 1945 when the plutonium bomb “Fat Man” exploded almost directly above it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments