Missing Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370: Satellite ‘pings sent five hours after contact was lost' the only clue in hunt for £160m plane

Theories to explain the disappearance of a routine flight have multiplied

Exactly one week after the passengers on Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 began boarding at Kuala Lumpur, the first significant leads have emerged. Evidence from satellite “pings” reveals that the Boeing 777 flew for up to five hours after all other contact was lost with the jet.

Yet many uncertainties remain, and theories to explain the disappearance of a routine flight to Beijing have multiplied to fill a vacuum of ignorance.

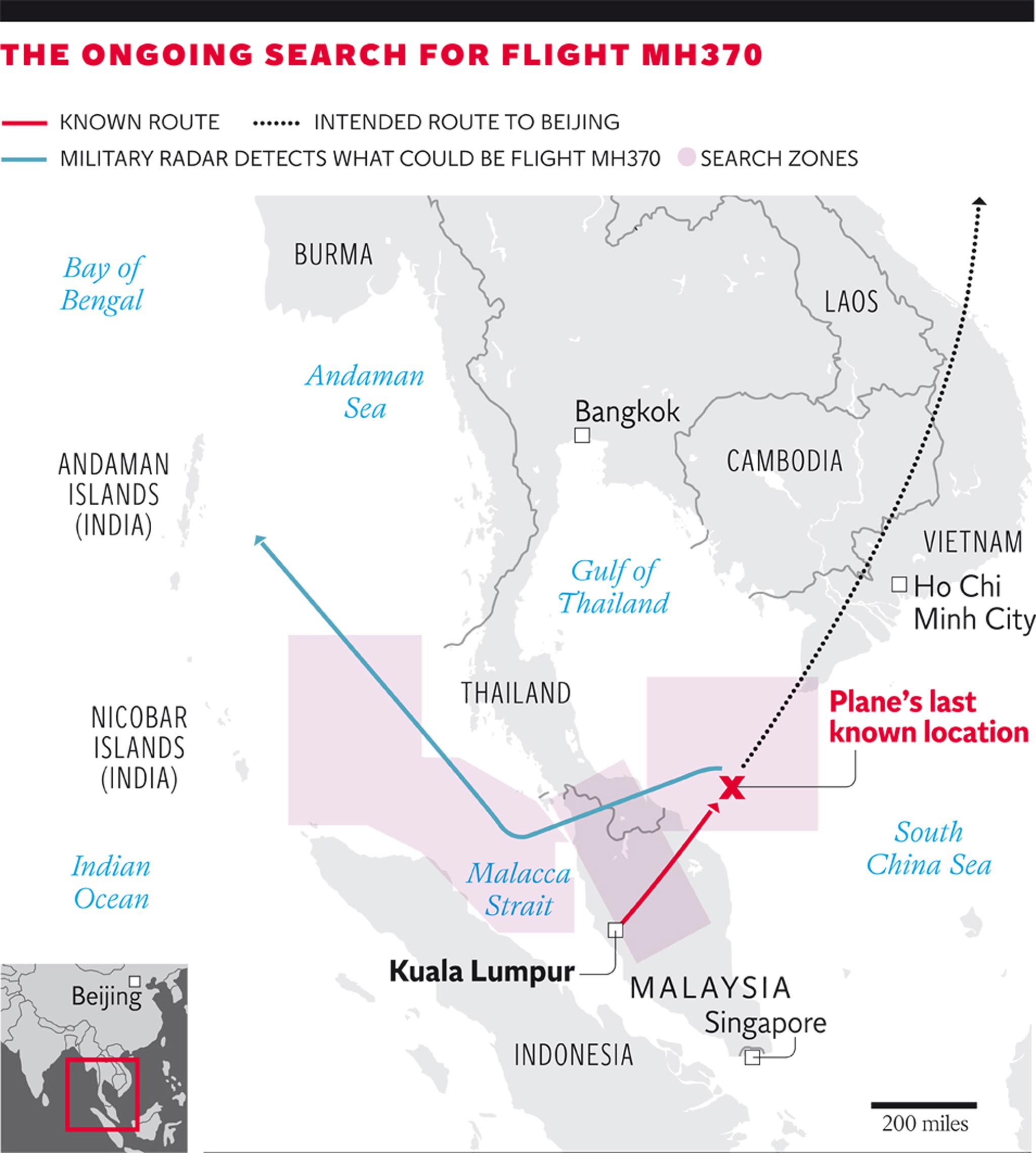

The known facts are sparse. Shortly after midnight local time last Saturday, 221 passengers and 12 crew departed Kuala Lumpur for the overnight journey to Beijing. At 2.40am communication was lost with the aircraft. At the time, the jet was over the South China Sea between Malaysia and Vietnam.

Malaysia Airlines reported the disappearance nearly five hours later, an hour after the plane was due to land in Beijing. The question of what happened to the jet has haunted the relatives of passengers - and the wider aviation community – ever since.

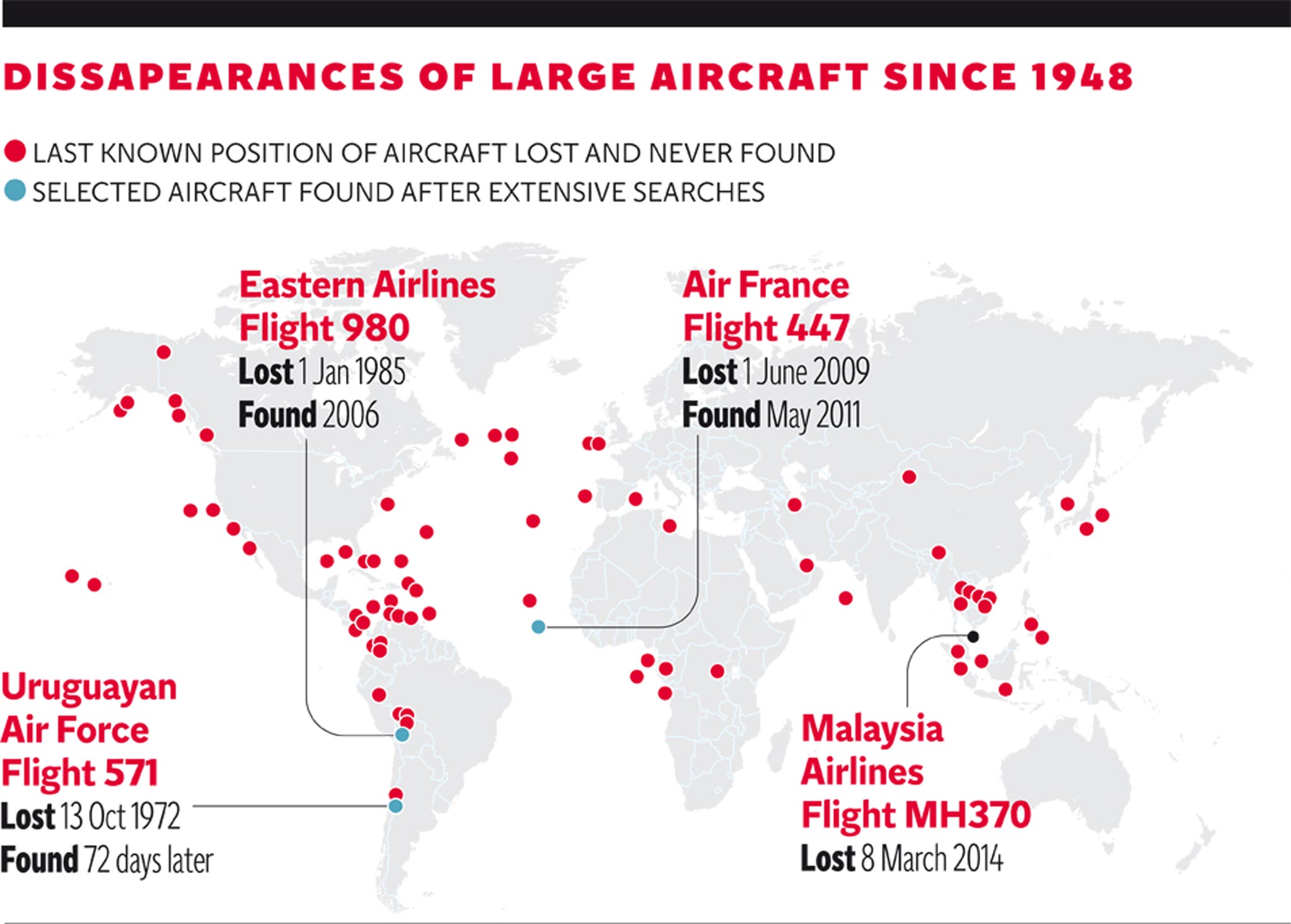

The jet's high-frequency radio fell silent, and the transponder stopped responding to radar interrogation. The spectrum of possibilities to explain the sudden loss of communication was wide. The cause could have been wholly accidental, for example a catastrophic failure of the airframe or hazardous cargo. A technical problem might have been exacerbated by pilot error, as happened with the crash of Air France 447 between Rio and Paris in 2009. A bomb may have exploded on board, as with Pan Am 103. Or de-pressurisation could have incapacitated the crew. But the revelation that the aircraft remained aloft on a different heading suggests that a pilot, or someone else who knew how to fly it, was at the controls.

While the search for wreckage continues, travellers are starting to question practices in international aviation – and asking how, given 21st-century communication technology, a large passenger jet can simply vanish. Since every iPad and iPhone owner can get an app that allows them to trace their device if lost, it seems absurd that a £160m, 250-ton jet aircraft should be untraceable.

Systems for locating an aircraft may be less sophisticated than for a smartphone, but have proved sufficient for normal operations. An obvious way to establish a plane’s location is to ask the pilots by radio. They constantly monitor their position with GPS and an inertial navigation system (a much older technology relying upon gyroscopes). The other method to locate an aircraft is to sweep the sky with radar. A passenger aircraft is fitted with a transponder, which responds to the radar by transmitting identification details and altitude.

Even though these normal communication systems were disabled – either by accident or design – one channel remained in operation. With many modern jets, if a satellite has not heard from an aircraft for some time, it sends out periodic interrogations. The Independent understands that the aircraft sent out an automated response, which is possible only when the plane is flying.

Based on the likely amount of fuel on board, the aircraft could have travelled a further 2,500 miles from its last-known location, extending to almost all of India and as far as the coasts of Australia and Japan. A circle with a radius of 2,500 miles has an area of almost 20 million square miles, one-10th of the surface of the Earth – giving a sense of the scale of the search-and-recovery task.

The limited data suggested that the aircraft flew west over the Indian Ocean, which is where search activities are now being intensified.

Meanwhile, speculation continues about MH370. Through social media, many preposterous explanations have gained traction. Early on, even Malaysia Airlines posited the possibility that the plane had landed at Nanning in southern China; sadly, it proved groundless.

As each day dawned with rumours but no further clues, speculation intensified. By Wednesday, LBC Radio invited callers to James O’Brien’s phone-in to explain the disappearance. “The plane has been kidnapped for spare parts,” insisted Patrick in Rickmansworth. “There never was a plane,” explained Geoff in Croydon; “It’s fake.” And the grieving relatives? “Crisis extras.”

Anger has grown among the families of the passengers at the lack of information since the plane failed to arrive in Beijing. As a result of the MH370 mystery, there are likely to be calls for smarter communication between aircraft and the ground. The US system of flight control, where a ground-based “dispatcher” shares responsibility with the captain, may spread worldwide.

The mystery has also revealed how easy it is to board an international flight using a fraudulent identity. Pressure will intensify for better security features on passports, such as embedded photographs, and airlines or border authorities may start checking passports against a database of stolen travel documents.

At the end of the worst week in its history, Malaysia Airlines has been powerless to do much beyond change the flight number. The service that departed Kuala Lumpur for Beijing exactly a week after the lost jet has been re-numbered MH318. The airline called it “A mark of respect to the passengers and crew of MH370 on 8 March 2014”.

When a flight number becomes shorthand for an aviation disaster, as Pan Am 103 did after the Lockerbie bombing, it is standard practice to erase it from the schedules. But unlike that tragedy, the fate of MH370 remains uncertain.

Most passengers are well aware that flying on major airlines is extremely safe. Confidence in Malaysia Airlines is likely to be dented in the short term, though past experience suggests that bookings will return. The demise of Pan Am was blamed by some on passengers staying away post-Lockerbie, but the airline collapsed almost three years after the bombing.

The Boeing 777 has been in service for 19 years and has an excellent safety record, so it is unlikely that passengers will seek to avoid the aircraft – as some did when the DC10 was involved in a series of accidents in the 1970s.

For aviation as a whole, the concern is not so much that passengers will switch to different airlines or aircraft, but that some anxious travellers will simply stop flying.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks