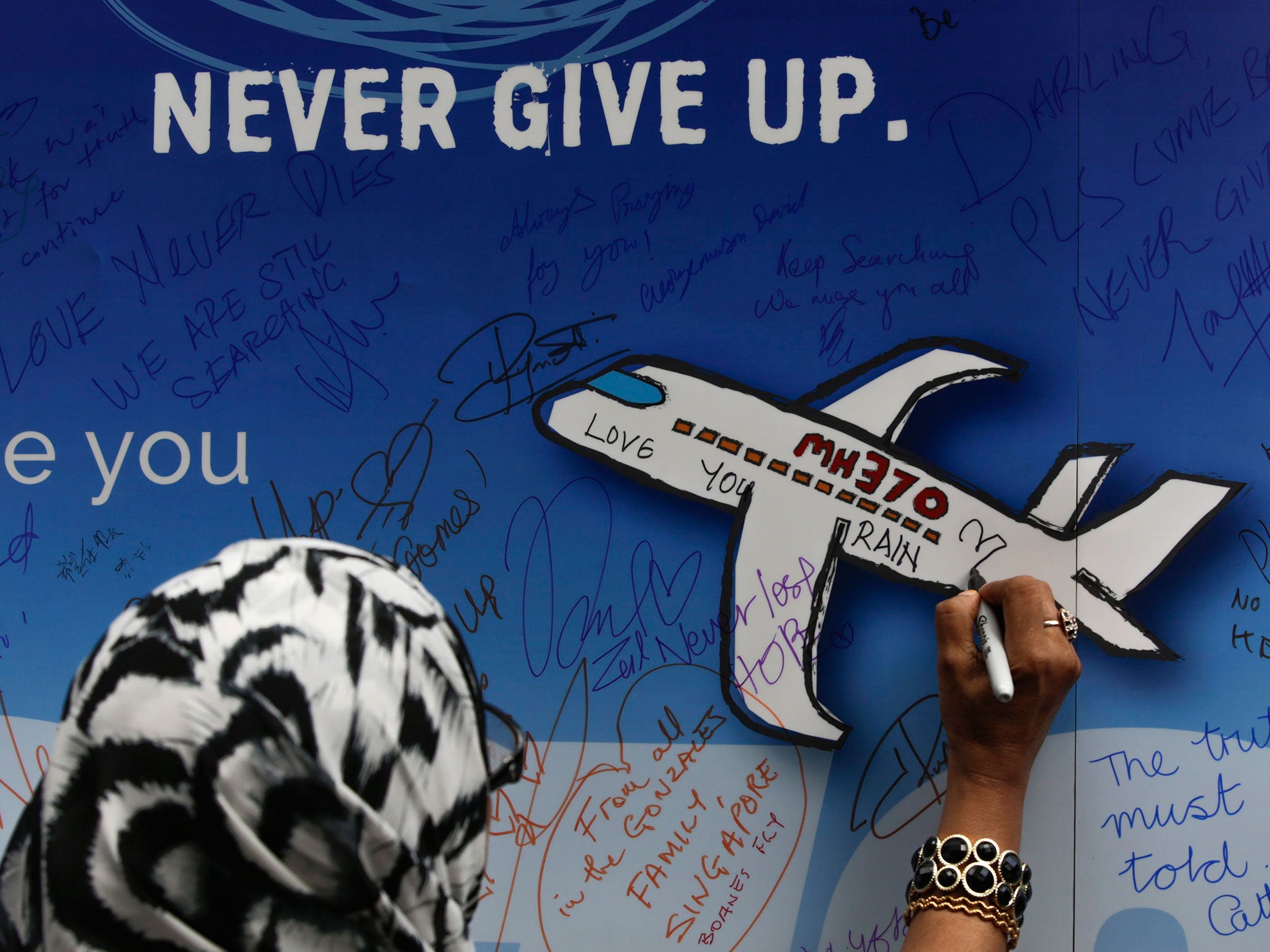

Two years after the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines jet MH370 and still no answer for grieving families

For the families of those on board missing flight MH370, answers are still required

By Tuesday, Jacquita Gomes will have been waiting two years to know how her husband, an in-flight supervisor, met his death in one of aviation’s great mysteries.

At a shopping mall in Kuala Lumpur, the Malaysian city that Patrick Gomes, along with 238 other people, departed on 8 March 2014 on board flight MH370, Ms Gomes said the families are fighting for the search to continue. “Our loved ones are not home yet, so how can we say it’s the end?” She added: “I think we are done with the sobbing and wailing. We do cry in silence. We have faces full of smiles, but behind the smiles, there is sadness. We have not reached closure.”

A search in the southern Indian Ocean has found no trace of the Boeing 777, though a wing part washed ashore on Réunion Island in the western Indian Ocean last July. The search is expected to end in June. Another suspected piece of the wreckage washed up in Mozambique last week.

Johny Begue, the man who found the wing fragment on Réunion Island, claimed to have found more mysterious debris, a square-shaped gray item with blue border, in nearly the same spot. A special gendarmerie air brigade in Saint Denis, the capital of Reunion, confirmed it received the item.

“We may never recover from this if it’s classified as an aviation mystery and the case is then closed,” the families of MH370 said in a statement. “If this is left unsolved, then how will we prevent it from happening again?”

Jiang Hui, a 41-year-old from China, said his life has been in limbo since he lost his 62-year-old mother, Jiang Cui Yun, who was aboard the plane. He said he lost his job as an IT engineer a few months after the tragedy due to depression. He said he filed a lawsuit in China on Friday against Malaysia Airlines, not for the money but in the hope that it will bring some answers to the mystery. “I want to let my mother know that I will not give up,” said an emotional Mr Jiang.

With the search of a remote patch of ocean off Australia’s west coast drawing to a close and the plane’s wreckage proving stubbornly elusive, Jay Larsen, the American who designed a sonar device being used in the hunt for MH370, is among those feeling the pressure.

“I think there is some tension building as the end of the job comes nearer,” said Mr Larsen, whose Whitefish, Montana-based company built one of the devices scanning a mountainous stretch of seabed where the plane is believed to have crashed nearly two years ago. “Everybody wants to find this thing, including us.”

Mr Larsen has been involved with the hunt from the beginning, when marine services contractor Phoenix International Holdings hired his deep-water search and survey company, Hydrospheric Solutions, to provide the sonar equipment used on board the search vessel GO Phoenix. The Malaysian-contracted vessel participated in eight months of the hunt until June last year.

Most recently, Mr Larsen and his team flew to Singapore to load their sonar device onto a Chinese ship, the Dong Hai Jiu 101, which has just joined three other vessels scouring the southern Indian Ocean for the plane. He then travelled on board the Dong Hai to the west Australian city of Fremantle, and, after ensuring the sonar and his team were ready to go, bid them adieu last month as they set out for the search zone 1,100 miles to the south-west.

Mr Larsen’s company has a crew of eight people on the Chinese ship who are tasked with running the sonar system – or “flying the fish,” as he puts it. That “fish” is actually a 20ft long, 5ft wide, 3.5-tonne bright yellow behemoth called the SLH ProSAS-60, which is dragged slowly behind the ship by a cable. The device hovers just above the seabed as it scans a patch of ocean floor 1.2 miles wide, sending data to computers on board that process the information into images.

The black-and-white, near-photo-quality pictures that pop up on the screen resemble the surface of the moon. The imagery, produced by synthetic aperture sonar, is higher quality than conventional sonar, Mr Larsen says, giving him confidence that his team will not miss the debris field if they drift over it.

The job can be gruelling. Mr Larsen was on board the GO Phoenix at the start of the search – from September 2014 to February 2015 – breaking only to return to shore once a month for fresh supplies. “It almost ruined my head, my brain, my heart, my marriage, but we got it going,” he said.

On board, two teams of three people work alternating 12-hour shifts every day, a job that requires close attention and co-ordination. One of Mr Larsen’s employees sits at the controls flying the sonar, while a navigator sits beside him looking at upcoming terrain to warn him of obstacles. A third person sits in a nearby seat providing a backup set of eyes. Another team member pops in occasionally in case anyone needs a break.

“It’s that whole cliché of hours of boredom interspersed with moments of terror,” Mr Larsen says. “Some of the terrain out there is just incredible, these mountains and trenches and stuff that we’re trying to get every last look into to make sure we don’t miss anything.”

The first month Mr Larsen’s team was on the hunt, they were in a constant state of alert, expecting the plane would quickly be found. As time passed, some of that anxiousness waned and the job became more routine. But they have never given up hope that the aircraft will be spotted, even though there’s just 30 per cent of the 46,000-square-mile search zone left to check. “It literally could be any minute – we could look up and see debris on that screen,” he said. “Everybody wants to be on the MH370 search.”

The seabed in the search zone is so remote that it had never been mapped before the hunt for MH370 began. The search has proven thrilling, though Mr Larsen is conscious of the larger goal. “We’re really proud right now to be a part of the search, because it’s a huge effort and I hope to bring resolution to those families. And that’s really the thing that drives us all: ‘Put a lid on this thing. Get this done.’” AP

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks