Meth addict has holes drilled in head for brain implants to stop him taking drugs

Yan says he is drug-free after ‘magical machine’ placed inside brain

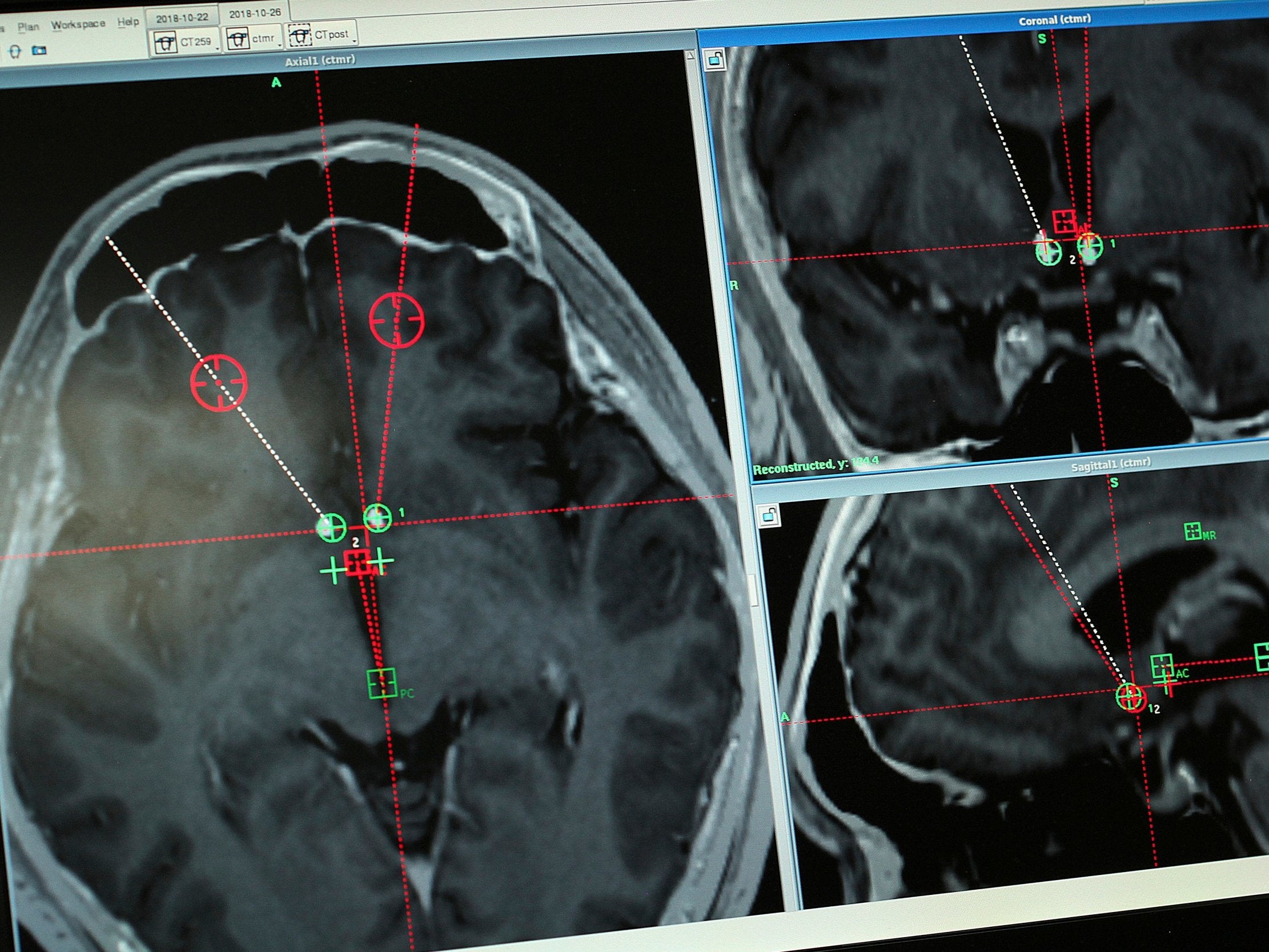

A methamphetamine addict has had holes drilled into his skull and electrodes inserted into the brain in the world’s first clinical trial to treat them with deep brain stimulation (DBS).

A pacemaker-type device was placed deep inside his brain by scientists at Shanghai’s Ruijin Hospital in China, to electrically stimulate targeted areas with the flip of a switch.

The experimental treatment has previously been used for movement disorders like Parkinson’s disease.

“The drill was like bzzzzzzz,” said the patient named Yan, the very first meth addict to undergo the treatment. “The moment of drilling is the most terrible.”

More than six months after the surgery, he said he was off drugs and had put on 20 pounds. The machine in his brain was “magical”, he said, adding: “It controls your happiness, anger, grief and joy.”

Western attempts to push forward with DPS for drug addiction have floundered due to ethical and scientific questions, but China has emerged as a hub for the research.

Globally, there are eight registered DBS clinical trials for drug addiction, according to a US National Institutes of Health database. Six are in China.

“For many other psychiatric disorders, for example, anorexia schizophrenia, OCD, there's no way to use the animal to be like a model,” said Dr Sun Bomin, director of the functional neurosurgery center at Ruijin Hospital. “For these kinds of special psychiatric disorders we have to use human patients.”

Some believe such human experiments for drug addiction should not be allowed.

Critics argue that they will not address the complex biological, social and psychological factors that drive addiction.

Scientists don’t fully understand how DBS works and there is still debate about where electrodes should be placed to treat addiction.

“It would be fantastic if there were something where we could flip a switch, but it’s probably fanciful at this stage,” said Adrian Carter, who heads the neuroscience and society group at Monash University in Melbourne. “There’s a lot of risks that go with promoting that idea.”

But the US opioid epidemic may be changing attitudes to risks among doctors and regulators, particularly in the US.

More than 500,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in the decade ending in 2017, adding urgency to the search for new, more effective treatments.

Now, the experimental surgery Yan underwent is coming to America. In February, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sanctioned a clinical trial in West Virginia of DBS for opioid addiction.

The study lead, Dr Ali Rezai, director of the West Virginia University Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, hopes to launch the trial in June.

“People are dying,” said Dr Rezai said. “Their lives are devastated. It's a brain issue. We need to explore all options.”

Additional reporting by Associated Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks