Meet the asylum seekers who are building Japan’s roads, despite being banned from working

Despite a chronic labour shortage, Japan’s immigration policy remains tough. Nowhere is this clearer than in the treatment of those seeking refugee status under ‘provisional release’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Japan had 13,831 asylum applications under review in December last year. It was the largest number in the history of a nation with twice the population of the UK and which is often estimated to be more than 95 per cent “ethnically homogenous”. And a tiny figure compared to the million-plus pending applications in Europe, which is still coping with the stream of migrants from such war-torn areas as Syria and Libya.

However, Japan's apparent reluctance to take in foreign workers seems increasingly at odds with the reality of the nation's worst labour shortage in more than two decades. And while many politicians are loath to lower any barriers to immigration, the number of retirees is growing relentlessly in comparison to people of working-age.

Japan is investing heavily in robotics, particularly in old-age care. And Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has declared that the nation should address its demographic problems by putting more women to work – as well as encouraging the elderly to stay in the jobs market – before considering importing labour. But why? Because, as his advisor Masahiko Shibayama said last week, there is “an allergy towards the word ‘immigration’” in Japan. “People are worried about public security,” he said. “They worry that foreign workers would eat up Japanese jobs.”

That hasn’t stopped some companies from ignoring the popular will for the sake of their profits. In the construction sector, especially, there’s a growing black market in unaccredited foreign workers; likewise in manufacturing. Indeed it was reported last year that carmaker Subaru was enjoying a boom driven in part by the cheap labour of asylum-seekers working without permits. Now, with preparations underway for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, such illegal labour could increase.

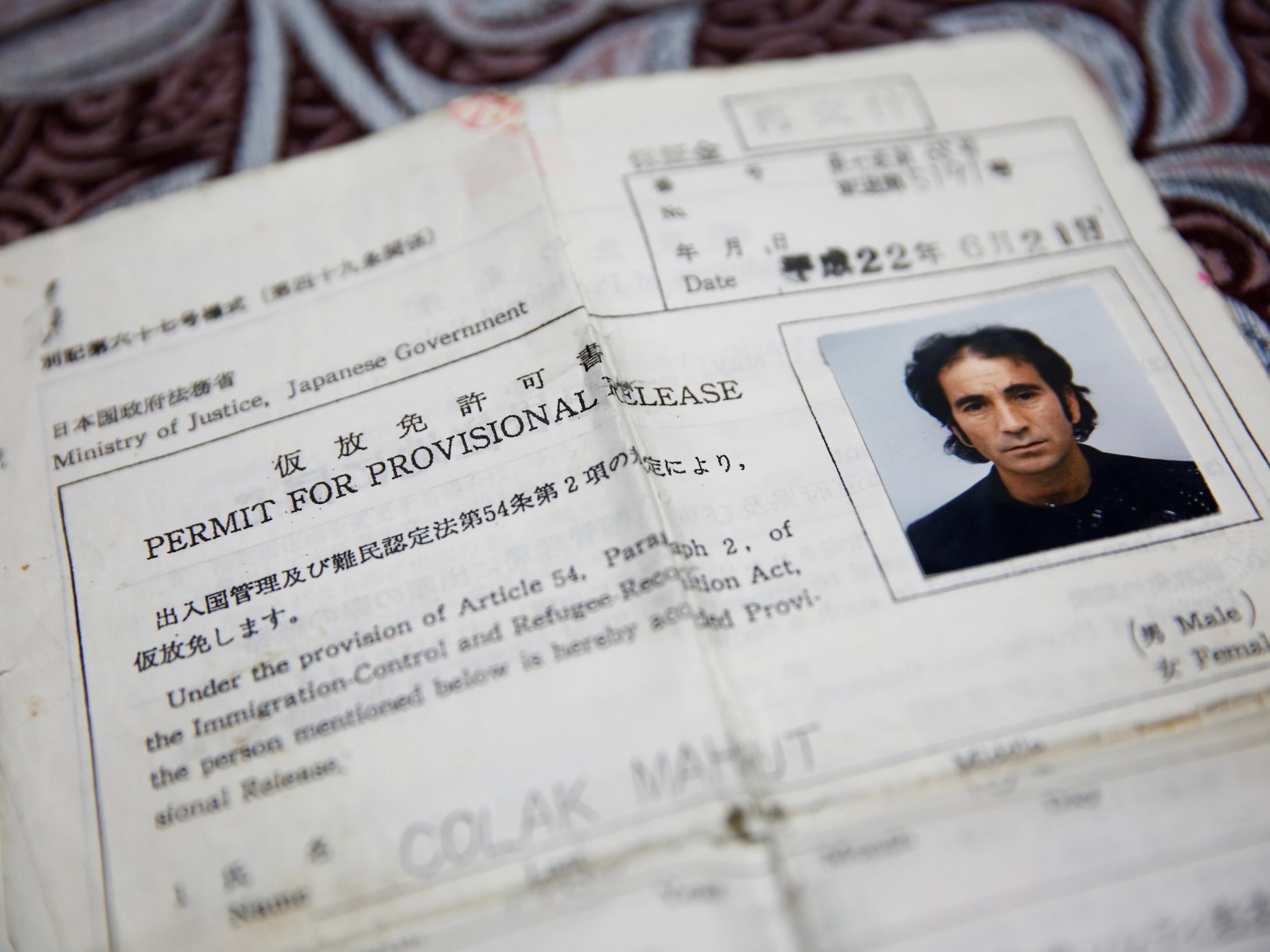

Many business leaders want the Government to rethink its immigration policy. Of 259 major Japanese companies that responded to a Reuters poll in October, 76 per cent said they supported opening up the country to blue-collar migrants. And prominent among the beneficiaries, no doubt, would be the Kurds of Warabi and Kawaguchi, central-Japanese cities in the Saitama prefecture that are embraced by Tokyo’s sprawl. According to the latest data, at the end of 2015 there were 4,701 people on provisional release in the country – that is, free from detention but officially barred from working while their asylum applications are considered – of whom Greater Tokyo’s Kurds represent about 30 per cent.

Living in drab, blue-collar suburbs with some of the highest crime rates in Japan – the area has been dubbed “Warabistan” by locals – Kurds who are working illegally while on provisional release don't have contracts, are paid in cash and can be laid off without warning.

Their status means they can be detained again at any time – though not deported while their applications are under scrutiny. They have no national health insurance, often leaving them with the agonising choice of debt or no treatment when they or family members fall ill. They cannot legally rent apartments, open bank accounts or sign up for mobile phone contracts in their names – a phantom status they navigate by borrowing the names and personal details of relatives and friends with residency permits. And they need official permission to leave the prefecture of their residence.

Mazlum Balibay, 24, a Kurdish asylum seeker who fled to Japan more than eight years ago is one of the phantom citizens. He arrived in the country claiming persecution by the Turkish security forces, who had tortured his father. The absence of a work permit hasn't stopped him, two of his brothers and a cousin from working on taxpayer-funded projects in the past few years. As he told Reuters earlier this month: “Everyone knows that without foreigners this country's in trouble. Construction jobs won't get done.” But then, he knows that the mayor of Kawaguchi – who recently declared, “I'm not going to tell these people they can't work when they have families to support” – has no intention of playing policeman.

Almost all the Kurds in Warabi and Kawaguchi are from villages around Gaziantep, an industrial city in southern Turkey. Starting in the 1990s, they entered Japan on tourist visas, fleeing violent clashes between the Turkish state and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in the Kurdish homelands. Balibay says his own family decided to leave after his father's arrest in 1999 on charges of giving aid to members of the outlawed PKK, including transferring funds collected in Japan for the group.

Over several years, Balibay's parents and five of his siblings have come to Japan – which according to immigration activists, has never given refugee status to a Turkish Kurd. The family's asylum claims have all been rejected, and their time in Japan has been peppered with legal battles against deportation orders and detention. (Balibay has submitted four asylum applications, including one in August last year.) However, they remain on provisional release.

Government officials say that friends, relatives or NGOs should help asylum seekers caught in this limbo. But once out of detention, the reality is that provisionally released migrants are left largely to fend for themselves. Contractors risk a maximum (and seldom enforced) $30,000 fine and three-year jail sentence for employing them. Meanwhile, desperate to attract home-grown workers, the labour ministry has partnered with construction firms to recruit young Japanese people. Although their website shows a group of smiling young women in hard hats under the headline “Women who work in the construction industry are cool”, privately, civil servants admit the outreach has done little to make the industry more attractive.

Some will even concede that they have had an answer staring them in the face since the north-eastern earthquake and tsunami of March 2011, when the Japan Association for Refugees was inundated with offers of help from provisionally-released migrants. A group of Kurdish men – many on provisional release, many with construction and demolition experience – were given permission to leave their prefectures and make the journey to the worst-hit areas. In the coastal village of Rikuzentakata – which was swallowed by a 15-metre wave that killed 1,700 people and swept away thousands of buildings – the volunteers cleared rubble from roads and rice fields, and cleaned up damaged homes.

With Prime Minister Abe struggling to boost the economy, his ruling Liberal Democratic Party published a proposal to recruit foreign workers to sectors including nursing and agriculture in May. But for now, Justice Ministry spokesman Naoaki Torisu says there are “no plans” to change the prevailing system. “Just because there are people on provisional release,” he says, “doesn't change our stance that they should go home.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments