Partition at 70: Can India become the world’s largest economy?

Some now talk of the possibility of India, rather than China, emerging as the world’s largest economy later this century. Could it happen?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They used to talk about the “Hindu rate of growth”. This was the idea that the post-Partition, centrally planned Indian economy was destined to eke out a GDP expansion of no more than 3.5 per cent a year due to its stifling bureaucracy and, some said, the slovenliness of the population.

Adjusted for fertile India’s population growth this was translated into a miserable 1.5 per cent of economic growth a year.

While the economies of other formerly poor Asian “Tigers” such as South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong took off in the 1950s and 1960s, the sluggish giant of India seemed destined to remain forever in the slow lane – with most of its people languishing in poverty.

Or so it was thought. The Hindu rate of growth is now history – another silly stereotype exposed. For the past 25 years, the Indian economy has grown at an average rate of 6 per cent.

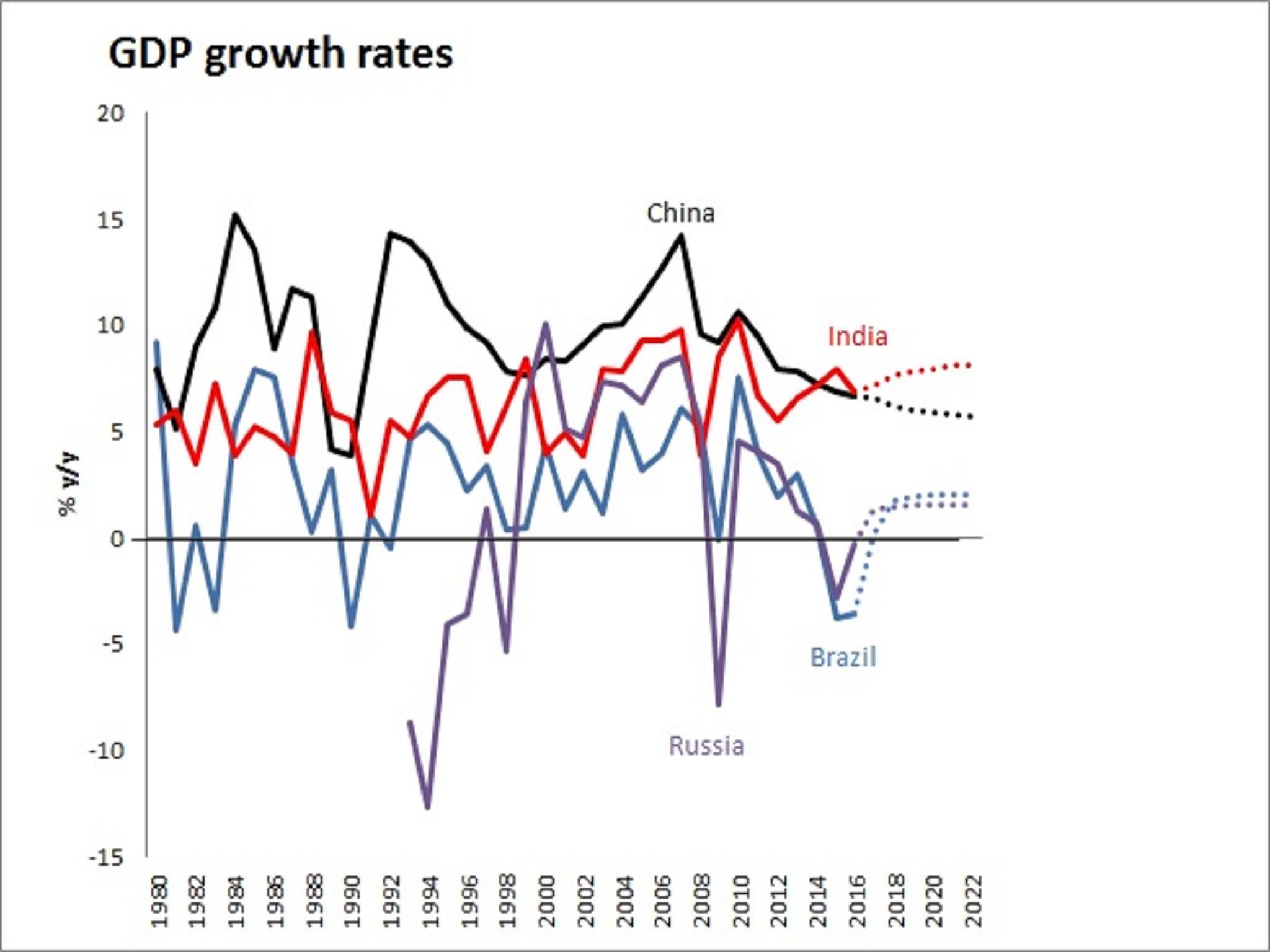

They used to talk of the new emerging market power houses of the BRICs – Brazil, Russia, India and China. But the economies of Brazil and Russia have slumped into crisis in recent years. And even mighty China has faltered – at least from its own ultra-high growth rates of recent decades.

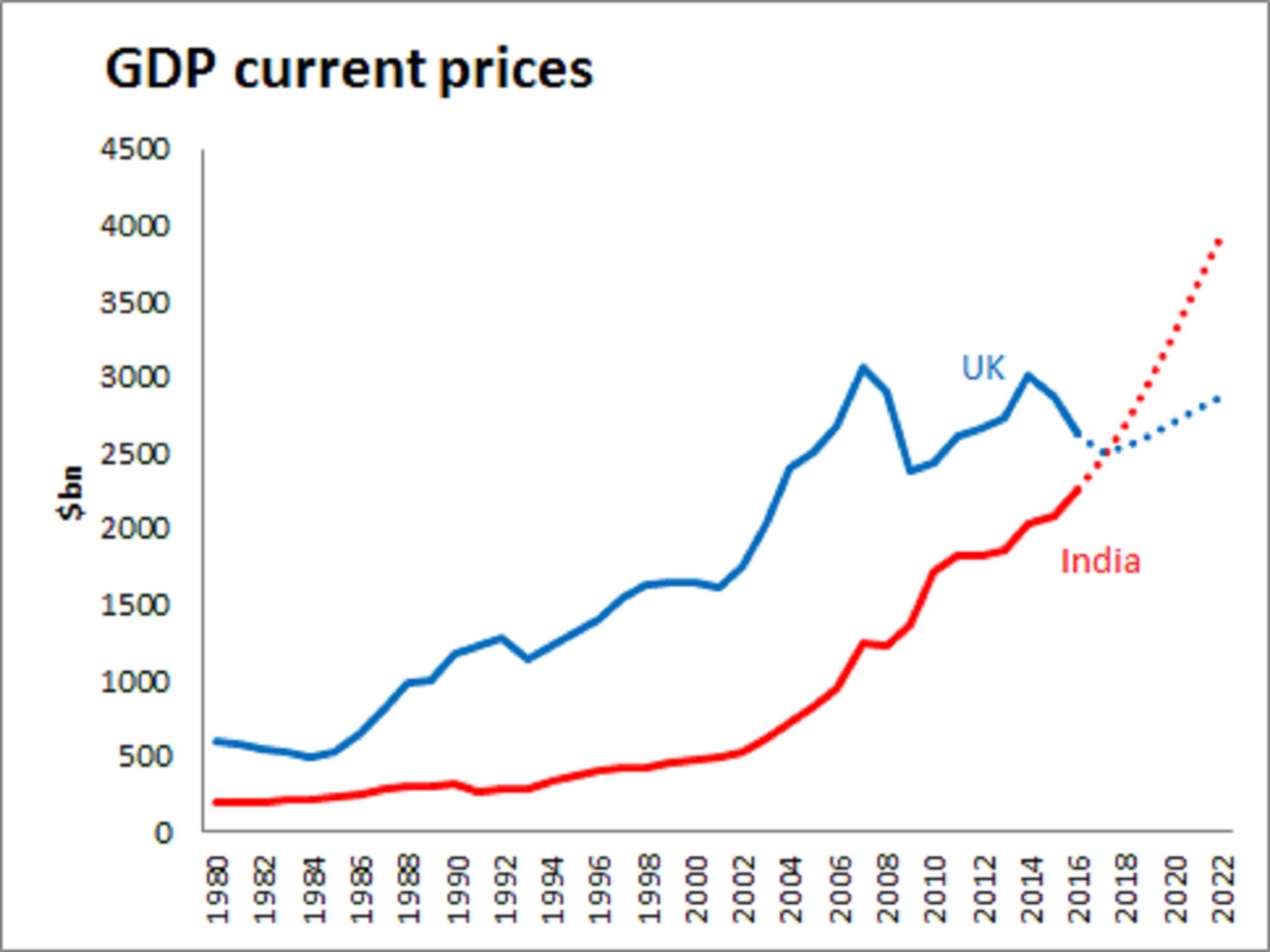

The IMF estimates that India outpaced China in 2015 (7.9 per cent growth versus 6.9 per cent) and will continue to outstrip the GDP growth rate of its enormous eastern neighbour over the next five years as well. The Fund expects the raw dollar-size of the Indian economy to outstrip that of the UK – the old colonial master which delivered Partition – in 2018, making it the world’s fifth largest economy. And some now talk of the possibility of India, rather than China, emerging as the world’s largest economy later this century.

Beating the rest of the BRICS

Could it happen? India has unquestionably made great, and surprising, economic strides in recent decades. The economic reforms of Manmohan Singh, first as finance minister in the 1990s and then as prime minister between 2004 and 2014, are the primary reason India finally started to motor. (Singh, incidentally, was born in in Gah, now in Pakistan, but migrated to India at Partition.)

Unlike in China, where the population is ageing rapidly due to the baleful legacy of Deng Xiao Ping’s one child policy, demography looks likely to provide a powerful tailwind to Indian growth over the coming half century. Around a quarter of all the people entering the global workforce between now and 2025 are projected to be Indian.

There were hopes that Singh’s successor as prime minister, Narendra Modi (who had a reputation as a friend of business) would take up the baton of liberalisation and take India to the next stage of economic achievement. But the Hindu nationalist’s record since 2014 has been disappointing overall.

Some fuel subsidies have been scrapped. A major new bankruptcy law introduced last year was welcome and may help the business environment – but the jury is still out. A new nationwide sales tax is certainly an improvement on what it replaced – but also a major missed opportunity for radical simplification. The elimination of most bank notes overnight was unquestionably bold, but has probably done less to rein in the black economy than the government claims.

Surpassing the old colonial master

Meanwhile, the land market remains unreformed. The national labour law is still a brake on hiring. Dominant state-owned banks are sitting on a mountain of bad loans. And, despite pockets of quality, the education system needs an overhaul. A fall in the global oil price (India is a major energy importer) has flattered the country’s growth rate in recent years – dulling ministers' appetite for politically difficult reforms.

On the surface India, the last "BRIC" in the wall, is standing tall and proud. But, beneath the façade, a great deal of maintenance and refurbishment, more than is commonly perceived, is needed if the country is to fulfil its economic potential, let alone reach the top spot in the global rankings.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments