Hospital on wheels brings hope to Indian villages

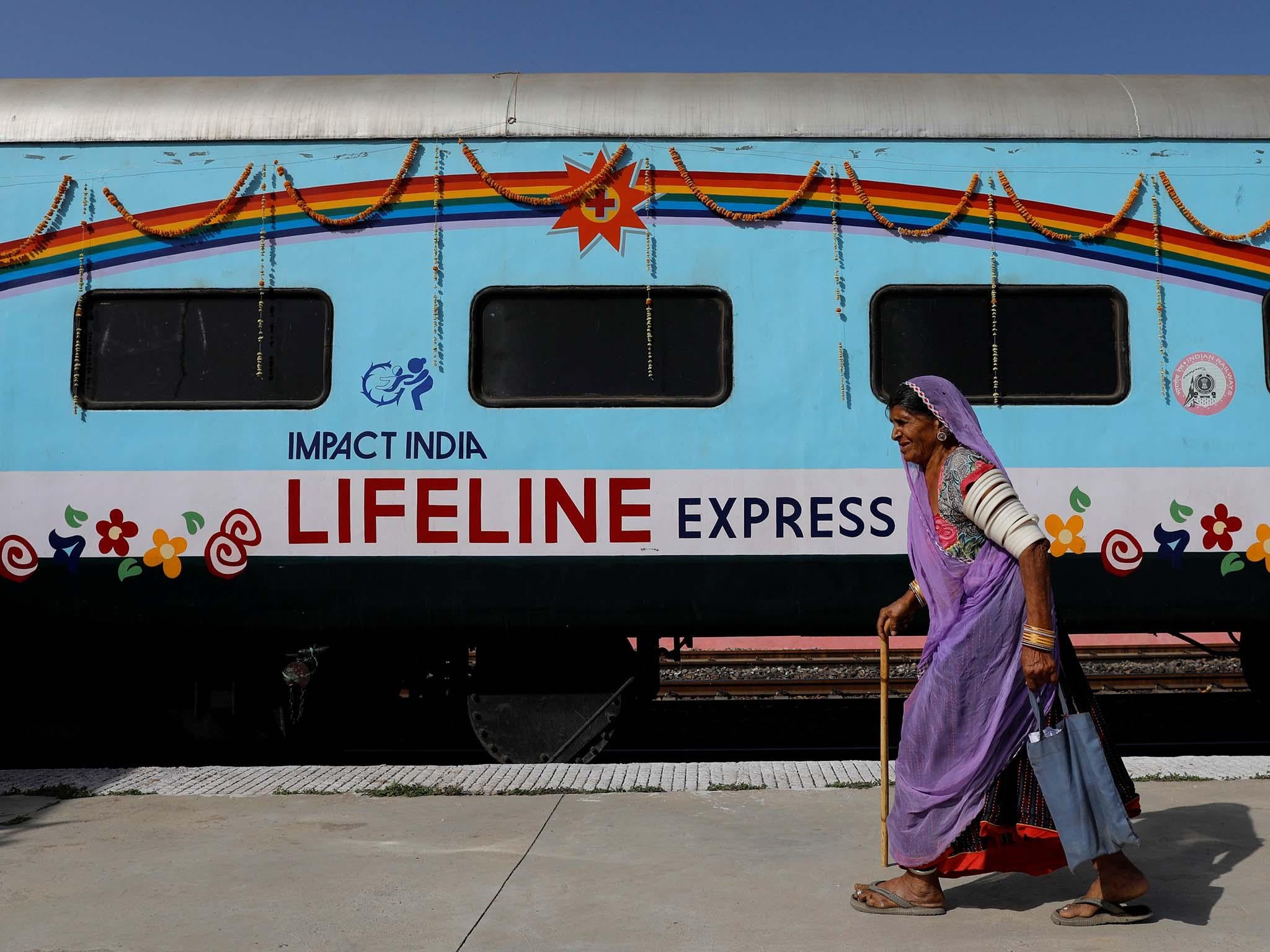

The Lifeline Express provides healthcare relief in scarce areas across India

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bhawri Devi, an illiterate Indian labourer, thought she was dying when she started to lose her hearing last month.

She went to a government hospital near her remote village in the western state of Rajasthan to be treated, but it did not have a specialist doctor.

The nearest private hospital was in the neighbouring state of Gujarat, and Devi was told her treatment, middle ear surgery, would cost about 50,000 rupees (£557) there.

“I didn’t even have 5,000 rupees,” says Devi, 41, who returned in despair to her home in Jalore.

Days later came news of visiting specialists who would treat her for free.

They arrived in early April as volunteers on the Lifeline Express, a seven-coach train converted into a rolling hospital that has crisscrossed India for 27 years to treat people like Devi living in areas with scarce healthcare.

Lifeline Express has treated about 1.2 million people since its launch in 1991 by the non-profit Impact India Foundation, says chief operating officer and doctor Rajnish Gourh.

In a country that spends just 1 per cent of its gross domestic product on healthcare among the world’s lowest, the hospital on wheels fills a critical gap.

Like Devi, India’s poor are caught between relying on a crumbling public health system trusted by few, or selling meagre assets to fund private treatment.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government launched a scheme in February that aims to widen health insurance coverage to 500 million people, but critics say the plan is unlikely to work unless public health systems improve dramatically.

Until then, options such as Lifeline Express offer crucial support.

Decorated with mahogany flower garlands, the sky-blue train parked at the sleepy station in Jalore could be mistaken for a new passenger train. Its medical facilities would rival many Indian public hospitals.

It employs 20 permanent paramedic staff, with most doctors volunteering from nearby medical colleges or hospitals.

Typically, it spends a month in a district, performing surgery ranging from cataracts and cancer to cleft palates and orthopaedics.

The aim is not to compete with India’s public health system, but support it. “We cannot have 100 Lifeline Expresses in the country,” says Gourh.

However, a second train will be launched in the next six months to cover the north and northeast, he adds.

Railways minister Piyush Goyal agreed to provide the second train at a meeting with Lifeline Express officials in February, Gourh says. The rail ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

The train gives volunteer doctors and medical students an opportunity to hone their skills while doing satisfying community work.

“Because we are working at the grassroots, we are exposed to different kinds of diseases,” says volunteer doctor Mehak Sikka. “You get to learn more.”

For patients like Devi, free treatment averts what could otherwise be a lifetime of suffering or death.

Feeling indebted to the young surgeon who treated her, Devi, clad in a bright yellow saree, joins her hands in respect before the doctor drew her into a warm embrace.

“I am glad that I will be able to hear my grandchildren’s voices,” Devi says, with a smile. “I won’t go deaf.”

Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments