India on brink of biggest gay rights victory as Supreme Court prepares to rule on gay sex ban

Landmark ruling will have far-reaching and direct implications for other Commonwealth nations that still outlaw homosexuality

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.India stands on the brink of the greatest breakthrough for gay rights since the country’s independence, activists say, as the Supreme Court prepares to rule on whether homosexuality is illegal.

While the LGBT+ rights movement has progressed in leaps and bounds across the Western world in recent decades, India remains one of a large minority of countries - around 40 per cent - that still criminalises consensual same-sex relations between adults.

A decision to decriminalise gay sex would have wide and far-reaching implications, not just for the status of the LGBT+ minority in India, but also for other countries across the Commonwealth that still enshrine this element of 150-year-old Victorian morality in their laws.

The Supreme Court began its hearing this week to decide whether to uphold a law commonly known as Section 377, a statute imposed on India and many Commonwealth nations by their British colonisers that prohibits “carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal”. Police and judges have widely interpreted this as referring to homosexual sex.

The law, the petitioners say, has fostered a taboo against gay sex and led in some cases to prejudice, discrimination and violence against members of the LGBT+ community.

Activists say the five judge bench has an opportunity now not only to do away with one of the worst legacies of colonial era rule, but also to issue a broader ruling on the rights of gay people in India to live free from persecution.

Hopes are high for a ruling in favour of decriminalisation, after the central government of Narendra Modi declared it would not oppose the matter and leave it “to the wisdom” of the apex court.

And during a hearing on Thursday, justice Indu Malhotra gave an early inkling of the court’s views when she declared that homosexuality “is not an aberration, but a variation”. “Because of family pressures and societal pressures, they are forced to marry the opposite sex and it leads to bi-sexuality and other mental trauma,” she said.

The case for decriminalisation is being fought by the former attorney general Mukul Rohatgi, one of India’s most senior lawyers, who told the bench that the “order of nature” referred to in Section 377 was not that of ancient Indian culture but rather “the Victorian morals of the 1860s”.

In an interview with The Independent, Mr Rohatgi says the court must show the world India is a “diverse society” and that “we will not tolerate these Victorian models of behaviour any more”.

He said he had been struck by the “harrowing” stories of petitioners who had suffered the impacts of Section 377 on their daily lives. They include Arif Jafar, an activist who wrote earlier this year about being tortured, abused and jailed for 47 days for his work educating the LGBT+ community about safe sex. Mr Jafar was charged under Section 377 for “conspiracy to promote homosexuality”.

Homophobia will not be eradicated from conservative Indian society overnight by a Supreme Court ruling. Among the arguments put forward in court this week by an association of mostly Christian religious groups, who want the ban maintained, was what Mr Rohatgi calls the “completely erroneous lie” that homosexuality is a disease to be cured.

But the court has an opportunity “to show the liberal world, the Western world, that India is not so far behind”, Mr Mohatgi says. “It would be a signal that India respects human rights, no matter what minority you belong to. The aim is that these people, who have been suffering, will be able to stand shoulder to shoulder with the rest of society.”

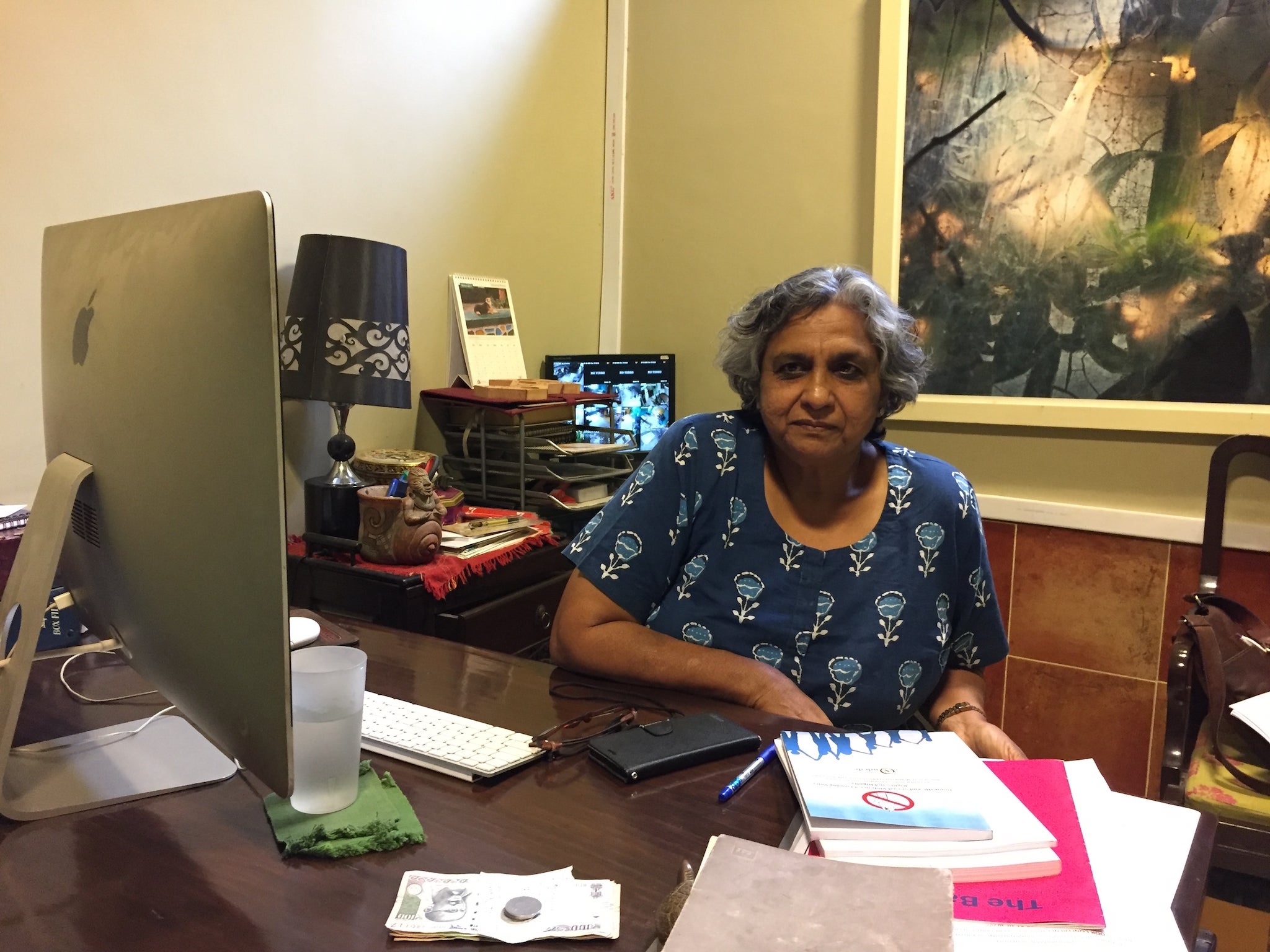

“It’s about time.” That’s the view of Anjali Gopalan, director and founder of the Naz Foundation HIV charity, speaking to The Independent in her Delhi office.

Ms Gopalan has a fair claim to being India’s leading proponent of gay rights. She is on the board of a number of the LGBT+ charities that have sprung up in the past 20 years, appears regularly in debates opposite leading conservatives on the matter and has been taking phone calls from TV news channels to give her reaction to this week’s momentous events.

She is in many ways a reluctant champion for the cause, fighting for gay rights on an essentially pragmatic basis; as the founder of an organisation supporting mostly men with HIV, she has seen the damage criminalisation has done to so many of the Naz Foundation’s beneficiaries.

But she also believes that the matter of gay rights goes to the foundation of what India strives to be as a nation - how can it claim to be a democracy, never mind the largest and most vibrant in the world, if it denies the most basic rights to a portion of its own citizens?

Ms Gopalan’s charity is at the centre of the legal battle over Section 377 - it was her petition, first filed in 2001, that led to gay sex being briefly decriminalised by the Delhi High Court. The ban was reinstated by the Supreme Court just four years later in 2013, however, amid objections from religious groups.

She admits it has been “a long journey” to get to this point, where the Supreme Court’s review of its 2013 decision is likely to be final. If the court does declare the ban on gay sex to be unconstitutional, Ms Gopalan says she believes there will be an “extraordinary” rush of people coming out as gay, the likes of which India has never seen.

“Just think about it - we have been stuck in the Middle Ages," she says. "The same people who wrote this law already changed it in their country. There is no reason for a country like ours to be sharing the same point of view as Pakistan, Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

“If we claim to be a democracy, then we need to behave like one. We are denying rights to people who are citizens of our country, based on who they want to live with and who they love.”

It may have taken almost 20 years for her to get to this point, but Ms Gopalan describes the impending Supreme Court ruling as “the end of one battle, and the start of another” to achieve fully equal rights for members of India’s LGBT+ community.

The government has explicitly warned the Supreme Court this week against going into details of gay marriage, adoption or other rights in its ruling, but Ms Gopalan says she will not rest until “everybody in this country enjoys the same rights”.

She has worked closely with gay communities across the world throughout her long career, and says that perceptions of homosexuality in India are a “mixed bag”. “There is a tacit acceptance of homosexuality as long as you ‘do the right thing’ by society,” she says, meaning starting a family.

“Often in family counselling sessions, parents have told me, ‘OK, I will accept that he is gay, but tell him to get married. What he does in his own time is his business.’”

She adds that nowhere is it “easy being gay”, “particularly in rural communities where you are that much more policed, and there is no anonymity”. “There it can be very difficult. And then added to that you have a law that criminalises you - never mind your rights, you are actively seen as a criminal.”

Ms Gopalan says she has received death threats for her work, “at least once a year, usually from the families” of gay men being assisted by the Naz Foundation. Some have been deemed serious enough to take to the police.

She also avoids the inevitably polarised debate on social media - having no account on Twitter, and hardly visiting Facebook - saying otherwise you could “never get anything done”.

But she does not fear for her personal safety, or for the future of the Naz Foundation if she steps aside, saying the charity is “in a strong position” to continue its work.

Once hearings conclude next week, the Supreme Court judges are expected to give their ruling in around four to six weeks - at which point, Ms Gopalan says, the new fight for equal rights begins. “It is going to be a long battle. This is just the first step.”

Aside from its huge importance in India, the ruling is being watched very closely by organisations that campaign for LGBT+ rights on an international scale. It will have direct implications for other Commonwealth nations that still use colonial-era laws to outlaw gay sex, according to the Human Dignity Trust, a legal charity which supports decriminalisation efforts around the world.

“India, as a leading and huge Commonwealth state, is about as important as it gets in terms of developing the law, and the impacts of what is going on there,” Téa Braun, the charity’s director, tells The Independent.

She says the 2013 decision to reinstate the ban was “a global upset” for the legal status of gay people, and if the review is successful “it will be enormous, not just for India but for the world”.

“Across the Commonwealth, judges refer to and rely on cases that came before in other jurisdictions,” she says. “Everybody is looking to India to see what they will do.”

One such country with a similar decision coming up is Kenya, where activists are also hopeful for a High Court judgement decriminalising gay sex later this year.

“A positive judgement in India would set a momentous legal precedent across all the Commonwealth countries that maintain these discriminatory laws,” says Jonah Chinga, a spokesperson for the Gay and Lesbian Coalition of Kenya (Galck). “Judges in Kenya are certain to inspect the India ruling and other precedents closely when making their own judgements on the consolidated Kenya petitions.”

For the Royal Commonwealth Society, a 150-year-old UK-based charity whose mission is to “promote the value and values of the modern Commonwealth” the tide of change is a welcome one.

The charity says it was instrumental, as part of a group called the Commonwealth Equality Network, in advocating for Theresa May’s recent expression of deep regret for colonial era legislation that discriminates against LGBT+ people and women and girls.

Dr Greg Munro, the chief executive of the RCS, told The Independent his organisation works actively “to build consensus about the need to reform colonial-era laws that discriminate against LGBT+ people”.

He says: “We’re delighted to see countries like Belize, Mozambique and Seychelles leading the way on decriminalising same-sex acts in the Commonwealth, and hope that India will join these countries in realising the rights of LGBT+ people.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments