The surprisingly cut-throat race to build the world's fastest lift

Each installation costs millions and companies barely make a profit, but that hasn’t stopped the race to build the world’s fastest lift from reaching new heights

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

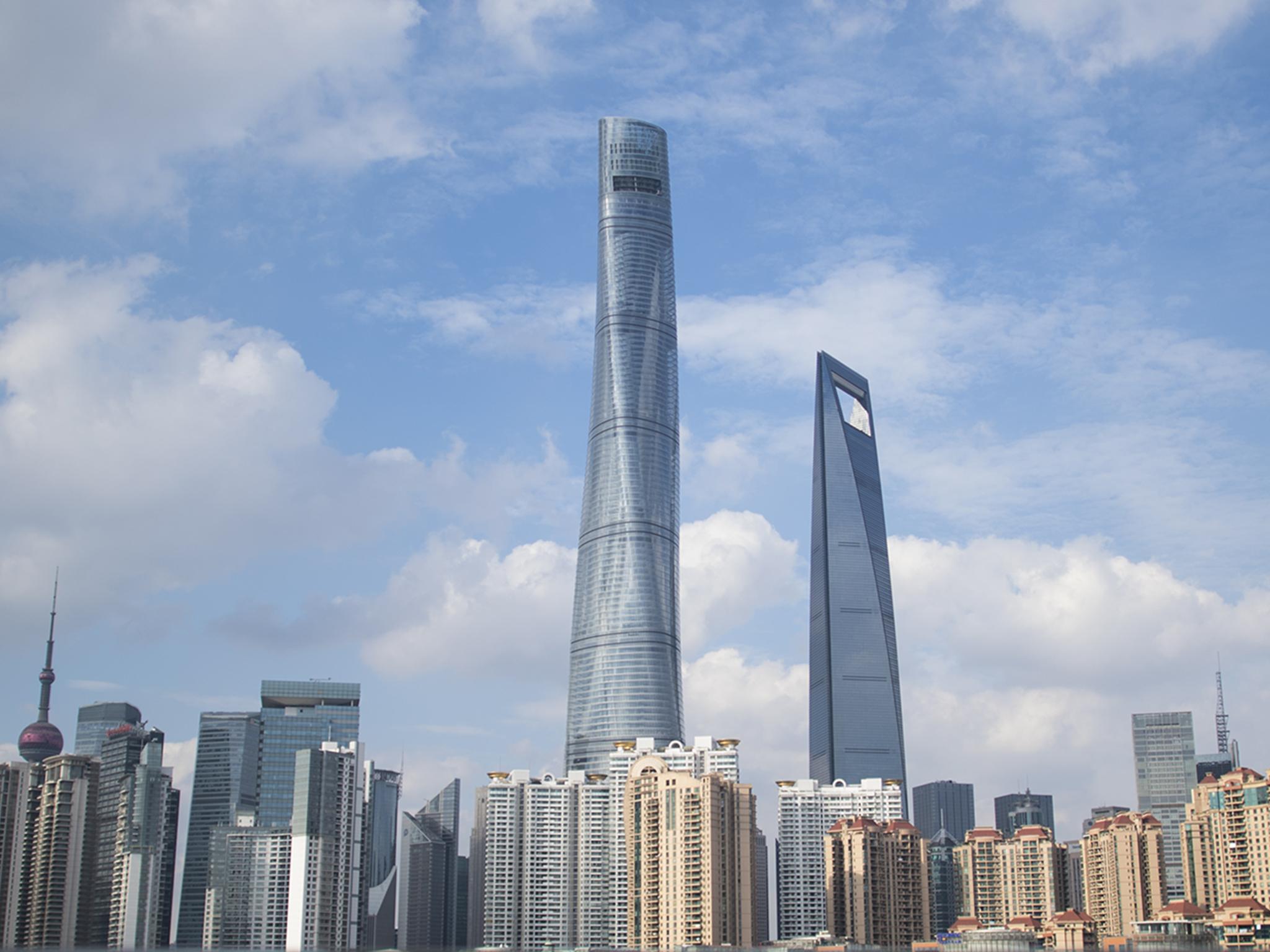

Your support makes all the difference.Lift rides are not usually worth documenting. But when you step into the lift at Shanghai Tower, people often pull out their cameras.

As the doors close, a screen at the lift’s front lights up to show you its location as it rises toward the building's newly opened observation deck. A neatly dressed attendant informs passengers that the lift has now reached a top speed of 18 metres per second, approximately 40mph.

“This is really fast,” one passenger said during a recent packed ride up the tower. It is, in fact, the fastest lift in the world.

At a ceremony in Tokyo in early December, the Shanghai Tower lifts and the company that made them, Mitsubishi Electric, were officially awarded the title by the Guinness World Records. Yet many passengers may not even experience the top speed. To do so, you have to travel in a souped-up lift with a Mitsubishi technician who can flick a switch, making the speedometer on the screen turn red: 20.5 metres per second (45.8mph).

China is experiencing a lift boom. Over the past decade, the vast majority of lifts installed around the world have been placed in China, where rapid urbanisation has met with a desire for ambitious “super-tall” skyscrapers. It has been estimated that by 2020, 40 per cent of all lifts will be in China.

And when it comes to speed, the rest of the world can’t keep up.

The Burj Khalifa in Dubai is the only skyscraper in the world taller than Shanghai Tower, but its lifts go at barely half the speed. The fastest lift in the West, installed at One World Trade Centre in Manhattan, runs at a paltry 23mph. The Shanghai Tower’s lift goes even faster than the Twilight Zone Tower of Terror, a Disney haunted-lift amusement-park ride that hurls thrill-seekers at 39mph.

Look at a list of the world’s fastest lifts now, and five out of the top 10 are in China. But China’s vast lift market is slowing. As it slows, lift companies are becoming more cutthroat – at every level.

Companies such as Mitsubishi are in competition for huge contracts with companies from all over the world. Another Japanese lift company, Hitachi, came close to winning the Shanghai Tower contract. It was awarded one in Guangzhou instead and then announced plans to beat Mitsubishi’s speed with its own 44.7-mph lifts.

In the end, Mitsubishi installed new hardware on one of the lifts in Shanghai Tower, snatching the record back from Hitachi shortly after it was lost. Mitsubishi representatives said that the demands of the client, a consortium with links to the Shanghai municipal government, had prompted the decision.

“For Shanghai city, it’s their pride,” said Ko Tanaka, the former head of Mitsubishi’s China business. “They must be number one.”

The world’s first safety lift was installed by the American company Otis in 1857 in a hotel in New York City. It travelled five floors at a speed of less than half a mile per hour.

According to Lee Gray, an associate professor of architecture at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, speeds improved as lifts moved from potentially explosive steam engines to more-efficient hydraulic systems and on to electric traction systems. Visiting Europeans were soon unnerved by the speed of the lifts across the Atlantic.

“The Brits would visit the United States and they would say, ‘God, why is it going so fast?’” Gray said.

For much of the 20th century, the fastest lifts were installed in American cities. Then the speed race moved to Asia.

Why Japanese firms have dominated the market of high-speed lifts is a matter of debate. Some have reasoned that it is because of the technology shared with high-speed “bullet” trains, which Hitachi and Toshiba also make. Others have suggested that it may be because Japanese consumers are notorious for insisting upon smooth lift rides. (Comfort and noise issues with ultra-fast lifts are considerable; the Pan Am building’s lifts in New York were infamous for “howling”.)

What is certain is that these lifts can cost fantastic amounts of money. They need to be tested in enormous, custom-built towers. They have to be pressurised to make their rapid ascent comfortable. According to Mitsubishi, 40 people worked exclusively on the Shanghai Tower lifts.

Mitsubishi and Hitachi would not say how much their lifts cost, but Jim Fortune, an American lift consultant, estimated each installation at up to $3m (£2.4m).

It would be hard for any lift company to make any profit on installing these showstoppers, Fortune suggested: “It’s all for ... bragging rights or to get that maintenance contract.”

Many in the lift industry say that while the technology is impressive, faster speeds do not serve a real purpose. But high speeds may be valuable as marketing tools, turning lifts into unlikely tourist attractions. And in an industry with its ups and downs, publicity can be important.

“Elevators are going to be weak in terms of business,” said Atsuya Fujino, the chief technology officer in Hitachi’s global lift and escalator division. “The fastest elevator in the world is going to be a very strong sales point for the company.”

The lift industry may have never been as unforgiving as it is now, but why is there so much growth in China?

Over the past two decades, China has rapidly urbanised. To boost urban density, hundreds of thousands of lifts and escalators have been installed each year. There are now more than four million units in the country – more than four times the number in the United States. Just more than a decade ago, there were barely 700,000.

There has also been a focus on super-tall buildings – 100 stories or more – in the Chinese market. In a country where there are more than 160 cities with a population larger than one million, such a building can help a faceless city stand out. “They want to build these signature buildings just so people would know where they are,” Fortune said.

Analysts say China accounts for 60 to 80 per cent of new installations globally each year. No one else compares. The second-largest lift market, India, is less than one-tenth the size.

The rest of the world may not have noticed, but those in the lift world say it has been a boom like no other.

“I’ve lived in an incredibly historic time for China, for our industry, in this country,” said Bill Johnson, head of the Finnish firm Kone’s China division since 2004. “I feel very fortunate, very lucky.”

But there is also a feeling that the glory days of the market are over – and that record-setting lifts such as those installed in Shanghai Tower may mark the end of an era.

China’s economic growth has slowed dramatically over recent years, dropping from more than 10 per cent to 6.7 per cent in the most recent quarter. A growing corporate debt problem and a much-feared real estate bubble – not to mention a potential trade war with the new US administration – add even more risk.

As demand for new lifts falls, major international firms have more manufacturing capacity than they can use. Meanwhile, low-end Chinese manufacturers are fighting their high-end international rivals for an increasingly small number of projects.

“It’s a brawl,” Johnson said. “There’s no question about that.”

According to the Shanghai Elevator Trade Association, around 5 per cent of smaller domestic lift companies have already gone out of business. Even for international companies, it has been difficult. In September, Kone announced that it expected the market for new orders to drop by 5 to 10 per cent over the next year. Its shares immediately fell by 3.5 per cent. American giant Otis has admitted to dropping prices to stay competitive, eating into its profit margin.

For Japanese firms such as Mitsubishi and Hitachi, the Chinese market is especially vital. These companies lack the international footprint many of their American and European peers have. And while they came to prominence during Japan’s own lift boom in the late 20th century, they now face a stagnating economy and a shrinking population at home.

Hitachi is still smarting over Mitsubishi’s surprise speed-record victory. When it won the contract for the lifts at Guangzhou’s CTF Finance Tower, Hitachi released a video showing its executives proudly proclaiming that they would take the record.

“I get tears in my eyes,” Akihito Ando, a Hitachi sales supervisor, said in the video.

The lifts are now operating, although the tower is not yet open. At the site, some staff members grumble about their short-lived record, suggesting that they could also modify the technology to make their lifts run almost 50mph and reclaim the crown. However, a Hitachi representative later said that there were no current plans to increase the lift’s speed.

If they don’t, when will the record next be beaten? Mitsubishi says that it has no plans to break its own record at present. Toshiba, which until recently held the record with the Taipei 101 Tower, said that it’s not focusing on ultra-high-speed lifts anymore.

“The competition for speed is over,” said Yoshinori Inoue, a communications representative for Toshiba.

But there could yet be new challengers. Hyundai, a South Korean lift manufacturer, has plans to begin testing 50mph constructions. Canny Elevator, a Chinese company based just outside Shanghai, is building a 3,100-foot test tower that it says will be the tallest in the world.

How much further the record can be pushed is unclear. One recent study suggested that 51.4mph would probably be the limit before passengers get sick. Travelling down quickly is even more difficult: Go too fast and the body thinks it’s falling. Lifts in both the Shanghai Tower and the CTF Finance Tower go down at 22.3mph, close to the limit.

Most importantly, even the most advanced lift still needs a big building to go in. Right now it’s unclear where such buildings will be. While many say that India could one day be the next China, Rizk Maidi, an analyst with German bank Berenberg, doubts it will ever be as ambitious.

“I don’t think we’ll see a repeat of the Chinese boom,” he said.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments